Colin Gibson, On Landscapes and Lives

Colin Gibson (1907-1998) was an artist of considerable merit - with successful solo exhibitions, commissions, a published book of words and woodcuts, and the accolade of the RSA’s Guthrie Prize in 1943 - when he decided to give up teaching to be a professional artist and writer after the Second World War. That led him towards illustration and nature writing, and his artwork has perhaps been overshadowed by his journalism. Gillian Zealand, Gibson’s daughter, reviews his legacy.

You’ll be hard pressed to find many of Colin Gibson’s works in public collections. Angus has some, and Dundee’s McManus has some fine drawings as well as a significant oil (of which more later). On the other hand, as I found out through a series of exhibitions and publications after my father’s death, an amazing number of people – especially in his native Angus - have their own ‘Colin Gibson collection’, perhaps an original painting of a familiar landscape or, more often, a file of cuttings from The Courier of his much-loved Nature Diary, which he illustrated with the distinctive scraperboard drawings of ‘Courier Country’ that became his hallmark.

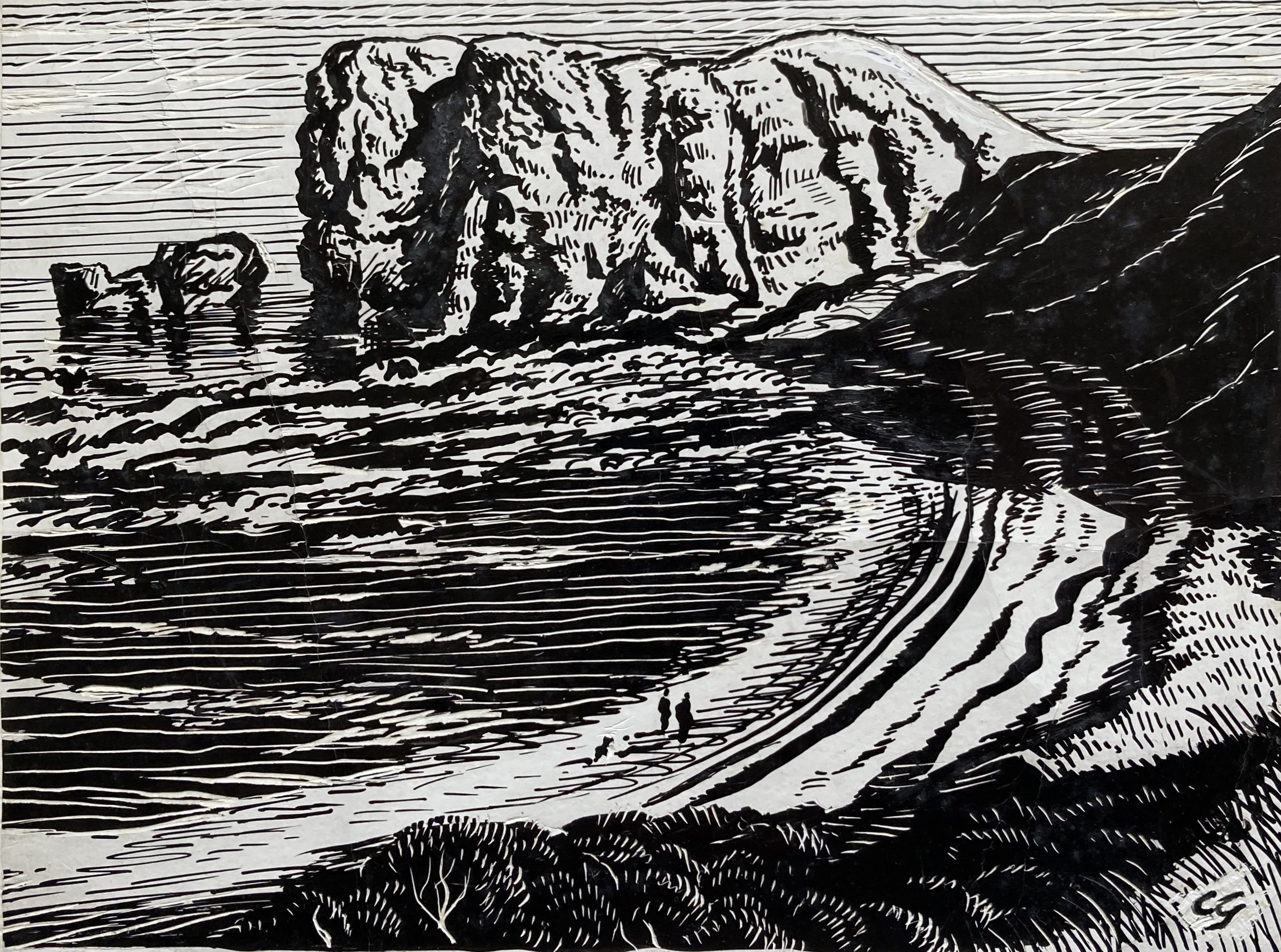

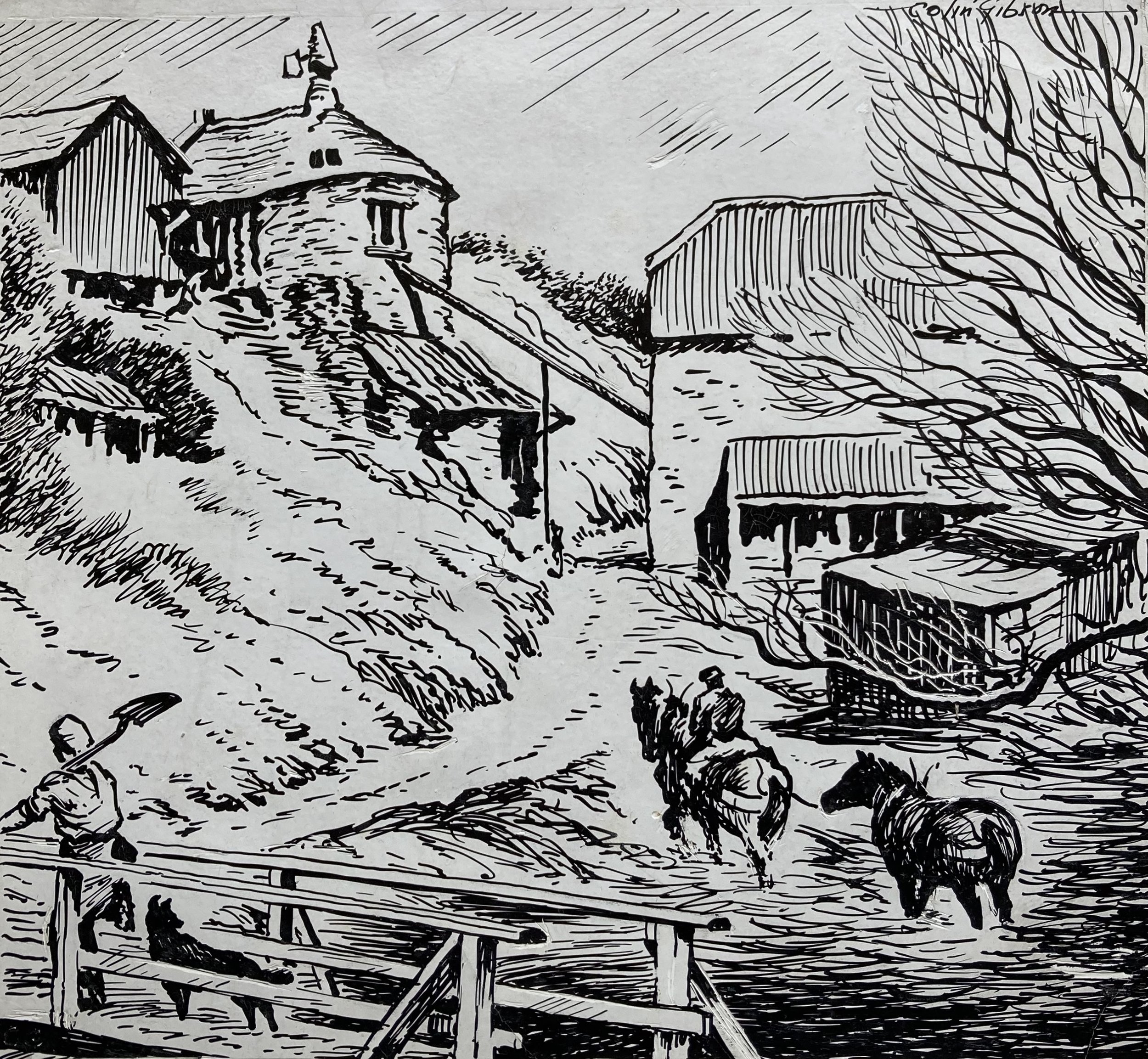

Colin Gibson, Lud Castle, ink on scraperboard, 12cm x 16cm, 1957

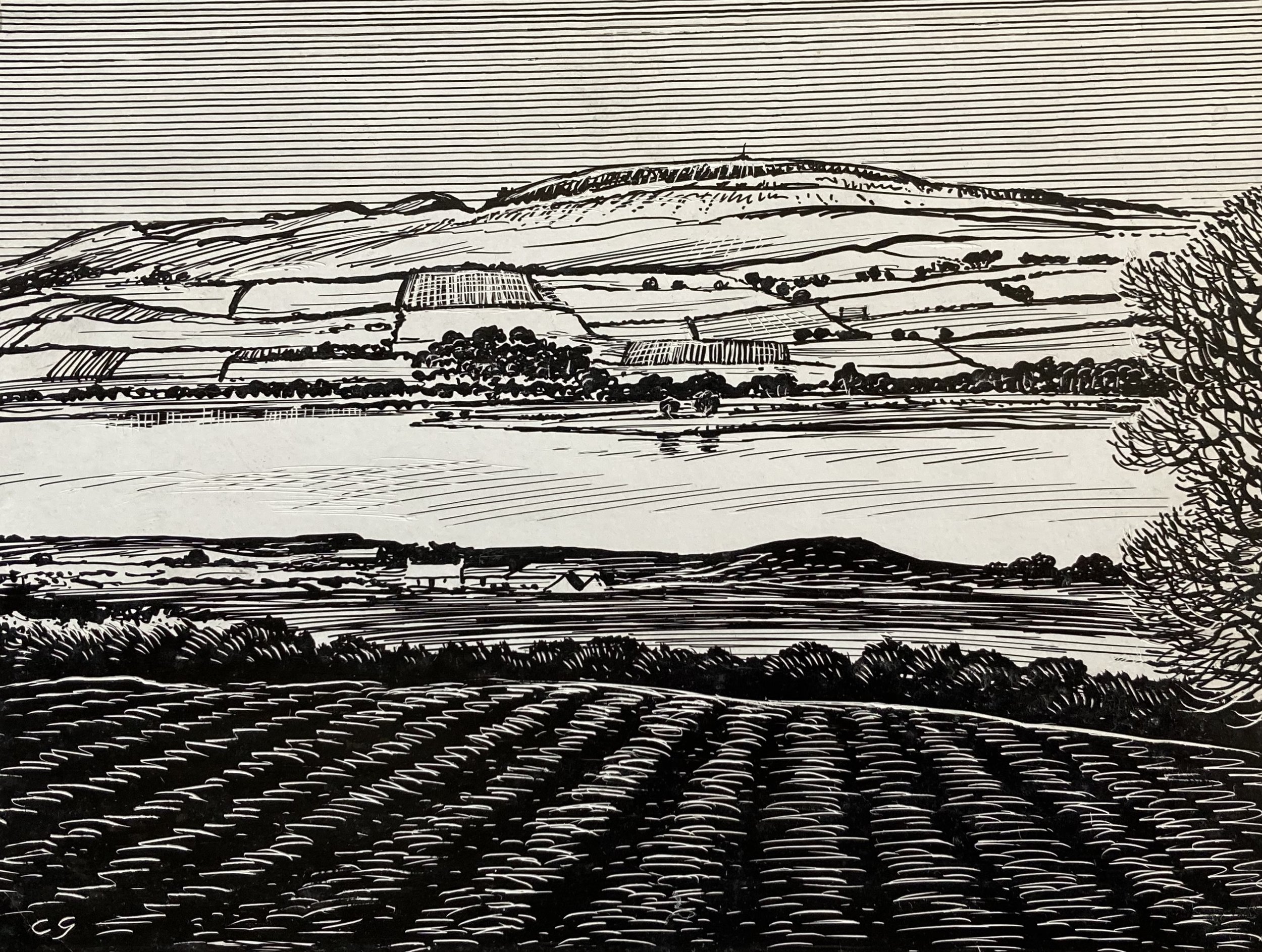

Colin Gibson, Rescobie, ink on scraperboard, 13cm x 17cm, no date

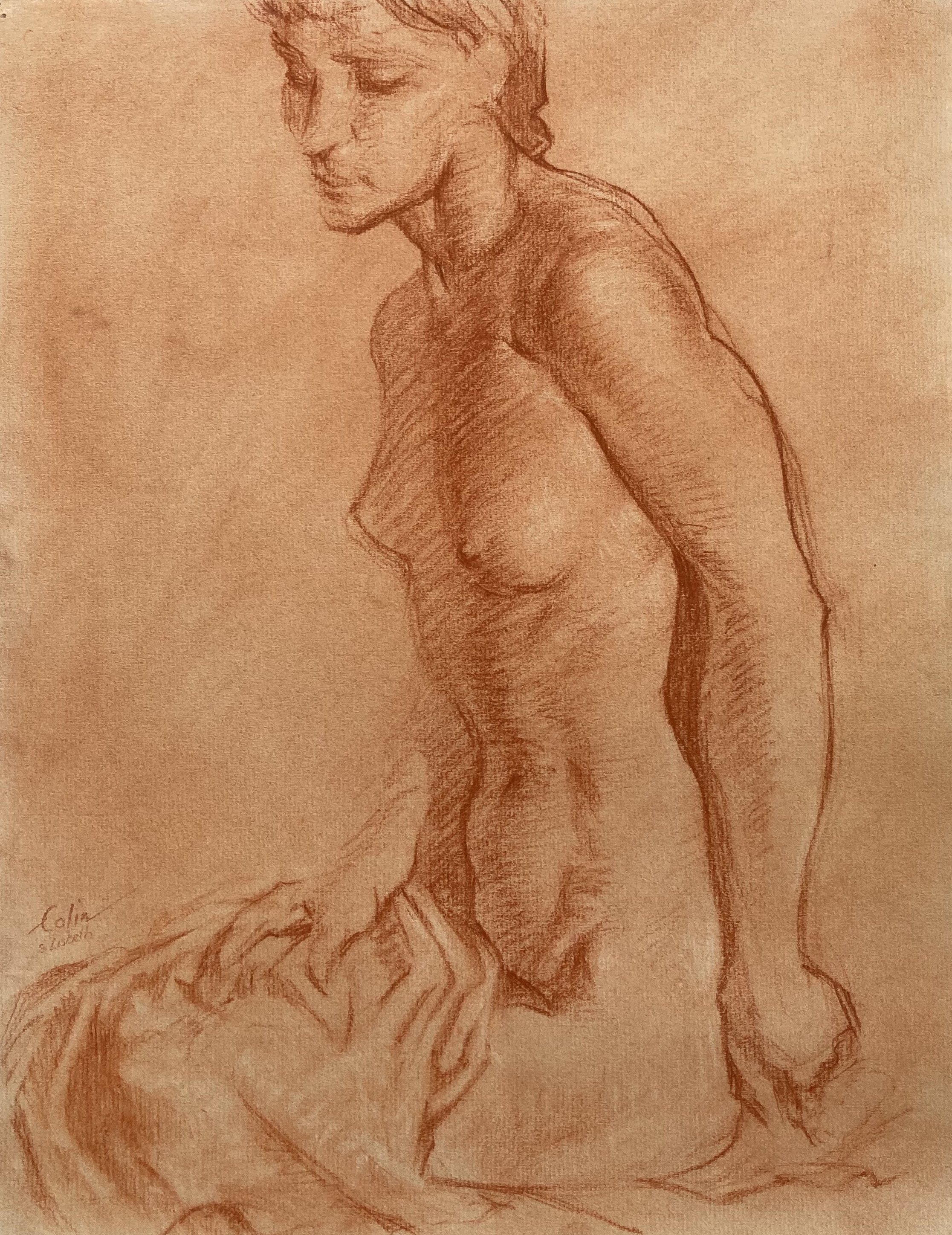

Illustration, in fact, is what Colin Gibson is probably best known for, and in terms of output these small works in pen and pencil, in numerous books, booklets, magazines and all sorts of miscellaneous publications, far outnumber his work in other media. Yet he was nothing if not versatile and his legacy includes large-scale oils (portraits and landscapes), murals, dramatic mountain scenes in watercolour and charcoal as well as gentler Lowland views, lively cartoons and a collection of beautifully executed life-drawings, mostly of his wife Lisbeth, my mother, done in red chalk. Many of these are still in my possession and are much cherished.

Colin Gibson, Sketch of Lisbeth, 31cm x 24cm, red charcoal on paper, c. 1940

Colin came from Arbroath and his love of the natural world was fostered by the fields, woods and fishing streams of the surrounding countryside as well as the dramatic sandstone cliffs. At Arbroath High School (where he was art medallist) his talent was encouraged by Alan ‘Paddy’ Inglis. His first commissions, while he was still a pupil, came from Arbroath’s two local papers: perceptive nature notes for The Guide, football cartoons for The Herald. In class he seems to have been an inveterate doodler: the margins of Macbeth, Horace’s Odes and Hume Brown’s History of Scotland (all of which I still have) sparkle with schoolboy humour!

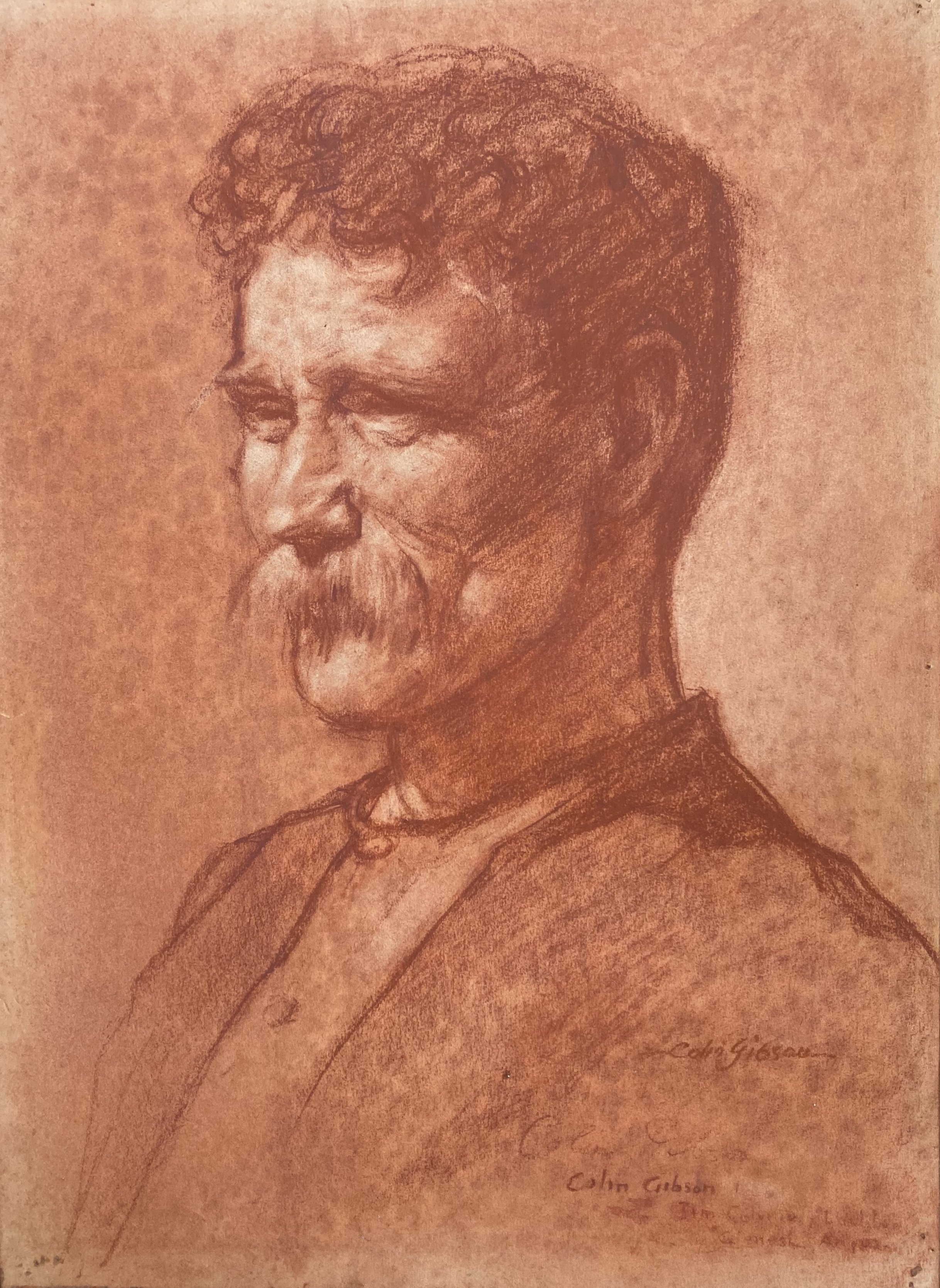

From 1925-29 Colin studied Drawing and Painting at Gray’s School of Art in Aberdeen. That Colin excelled in both is clear from the impressive number of prizes and scholarships he was awarded. A number of works survive from those times. A Gentleman of the Road (also known as The Pavement Artist) is a striking oil portrait of a white-bearded and dignified old man, his ruddy face evidence of a life spent out of doors (he was actually a well-known local tramp). Programme covers for student revues demonstrate Colin’s sense of humour, design skills and proficiency with the pen. Very different from both of these was his ‘royal commission’. Gray’s had been requested, at the instigation of King George V, to provide a student to ‘paint the deer at Balmoral’. Would my father like the job? He would! But his hopes of becoming a second Landseer were soon dashed, as what the king actually wanted was to have some statues in the castle grounds painted in realistic colours! Nonetheless, over his Easter holidays, Colin applied himself with gusto and soon had those stags bursting with life. The paint must have worn off years ago, but it was an experience he used to recall with relish.

Two travelling scholarships took Colin to Italy and Spain. He drew the Ponte Vecchio, painted Spanish ox-carts, copied Moroni in Bergamo and Velasquez in the Prado, and in Toledo found a fine subject in the bridges over the Tagus gorge, their arches and perspectives redolent of Piranesi. Back by the cold North Sea, the warmth and vitality of Spain lingered long. Earthenware jugs creep into his paintings and he wrote some imaginative short stories and memoirs.

Colin Gibson, Alcantara Bridge, oil on board, 40cm x 30cm, c.1930

Having gained his teaching diploma he found work as an art teacher, first at Ashington in Northumberland and then in the Art Department of Dundee High School under James Cadzow. Colin threw himself into school life, even designing the new DHS badge (still used today) and doing a portrait of the rector. During the War he took parties of senior boys to the Angus Glens to ‘do their bit’, hoeing turnips or working in the forests loading pit props; he enjoyed the company of these lively youngsters and got on well, as he always did, with the farmers and woodsmen. Many former pupils kept in touch to reminisce over their time with ‘Polly’, as he was affectionately known. Dundee High also introduced Colin to two lifelong friends, George Bruce and Tom Halliday, also at the start of their careers. Halliday became internationally known as a wood-carver, particularly of birds and animals. George Bruce, originally from Fraserburgh, was a poet and man of letters, a driving force of the Scottish Renaissance and friend of artists such as John Bellany and Elizabeth Blackadder.

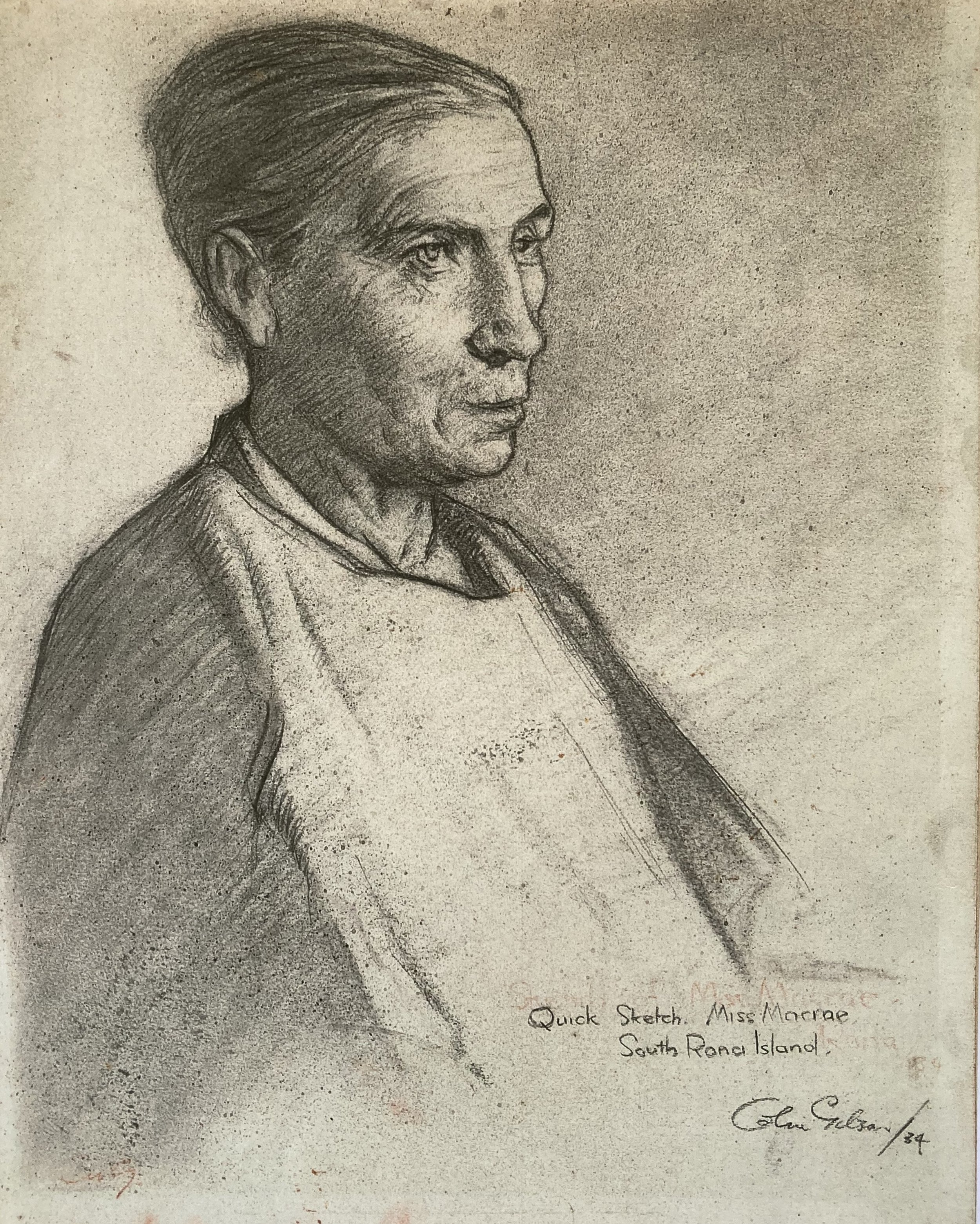

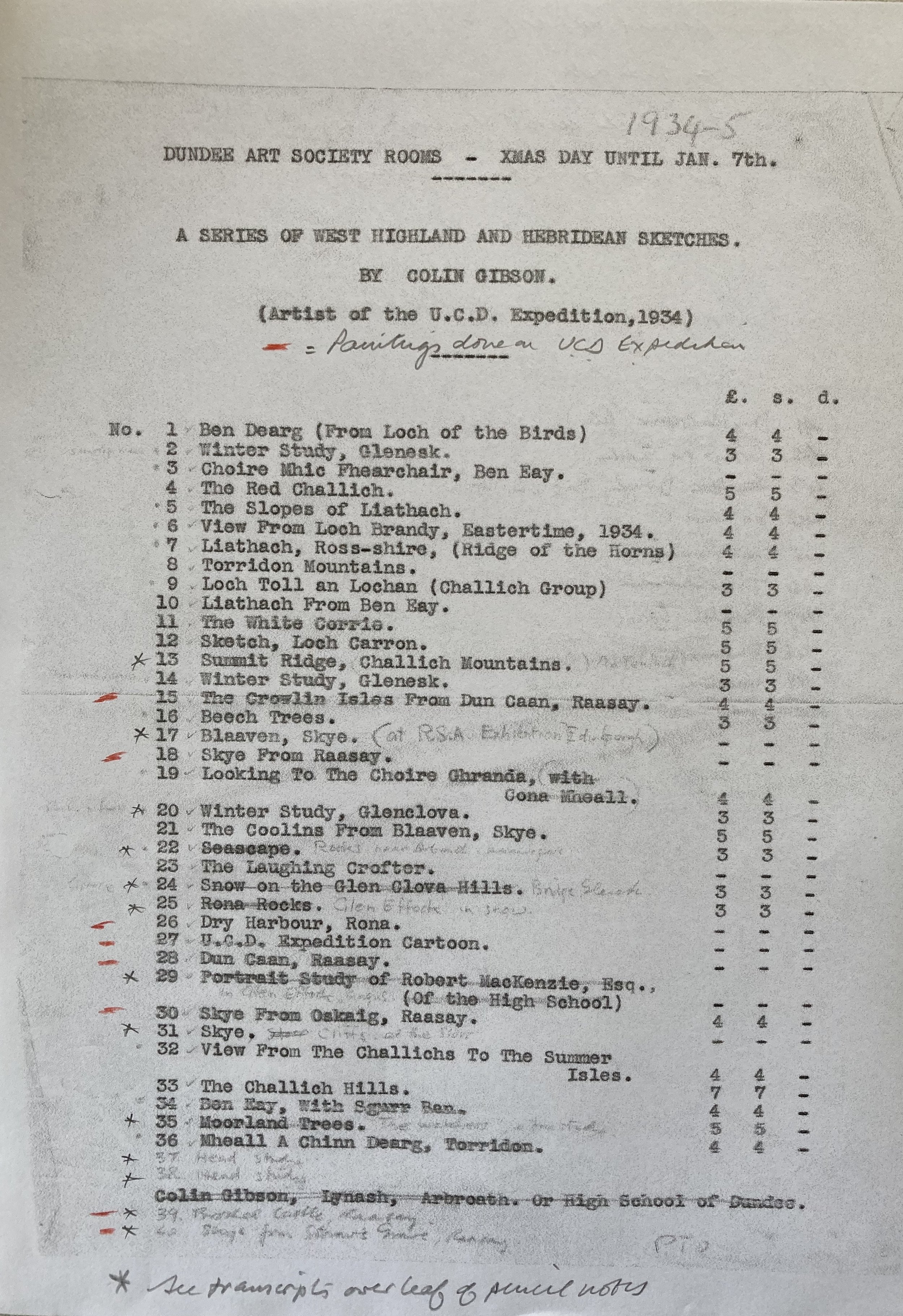

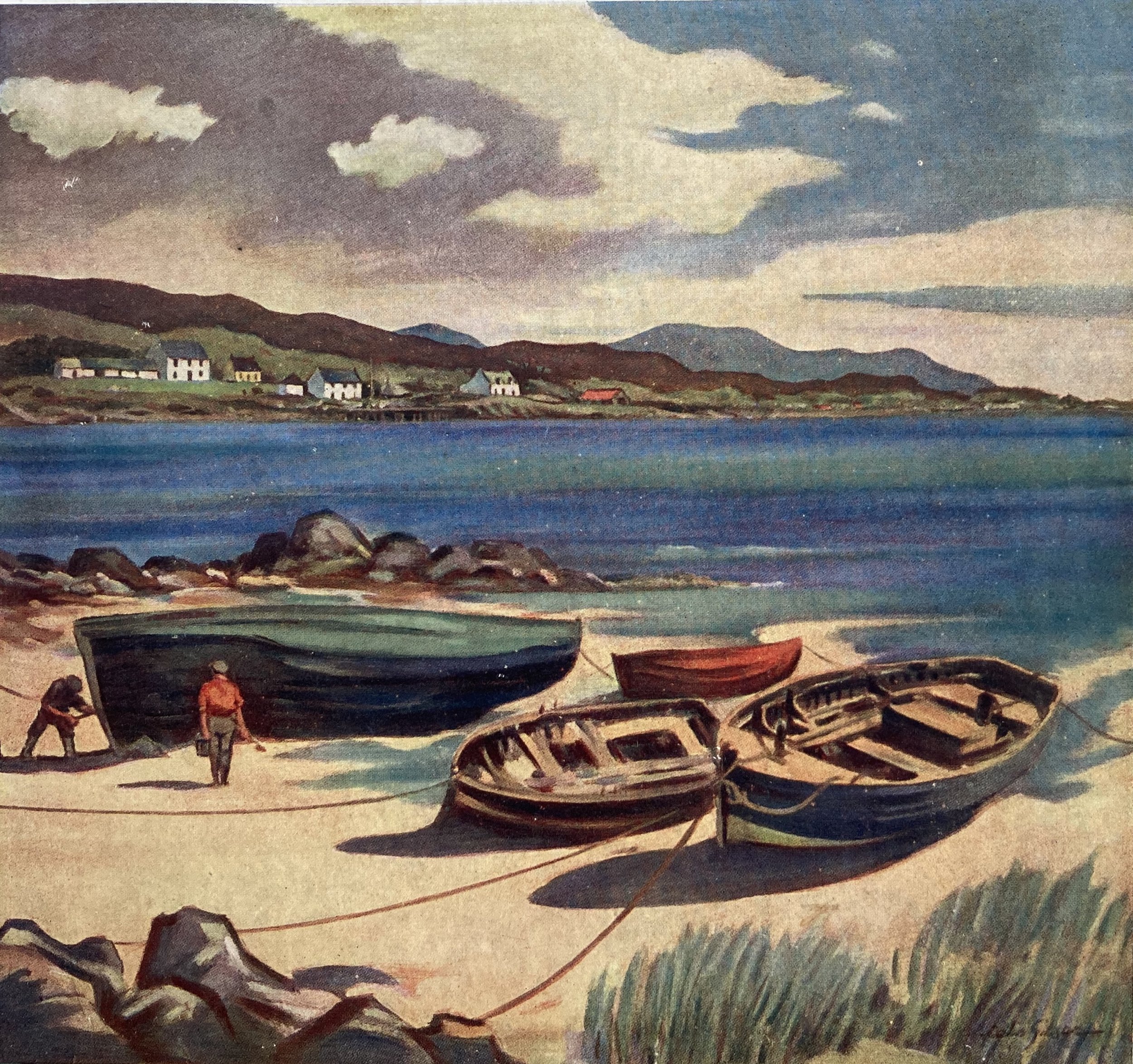

During these High School years Colin had a memorable experience: in 1934 he was invited to go as ‘expedition artist’ on a biological expedition organised by University College, Dundee (now Dundee University) to the Hebridean islands of Raasay and South Rona. Given free rein, he produced painting after painting of this landscape of land and sea, rocks and changing skies. On Rona he drew the members of the Macrae family (sole inhabitants, apart from the lighthouse keepers), and he immortalised the entire expedition in a marvellous cartoon, which is now in Dundee University. Some individual pieces went to academic departments or expedition members but there were still enough to arrange a showing the following year in Arbroath Art Gallery, where – Colin being a local lad - they attracted a lot of attention and were praised for their ‘clear conception and incisive handling’. Later they moved to Dundee Art Society. Supplemented with paintings of other West Highland and east coast scenes and a number of portraits, these were, as far as I can make out, Colin Gibson’s first solo exhibitions.

Unknown photographer, Colin Gibson (in hat, second left) on South Rona, 1934

Colin Gibson, Sketch of Miss Macrae, South Rona, pencil on paper, 33cm x 26cm, 1934

Dundee Art Society Exhibition Catalogue, West Highland and Hebridean Sketches by Colin Gibson, 12.34 - 1.35

It has to be said that my father – like most of his pupils no doubt - lived for the holidays. He was captivated by the north-west. The mountains of Torridon and Skye, especially, drew him and he captured their soaring peaks and ice-carved corries in charcoal and watercolour, the mediums he found best suited to the ever-changing weather and fleeting effects. Back in his studio some of these works were translated into larger pieces but the plein air originals have a wonderful atmosphere and immediacy, even if – or perhaps especially when – speckled with rain or painted with peaty water squeezed out of a clump of damp moss.

Colin Gibson, North from Liathach, watercolour on card, 29cm x 39cm, c.1938

But art was not only for holidays. Along with his mountain landscapes, Colin was amassing a growing collection of life drawings and some of these he worked up into large oils, manipulating the classical realism of the originals – in which he had been trained – to exploit the tensions between the facts of anatomy, the constraints of the frame and the search for a strong design. Several of these striking works were accepted by the RSA and in 1943 he received (jointly with Alberto Morrocco) the Guthrie Award for the most promising young artist of the year for his portrait of ‘Lisbeth’, the oil now in the McManus.

Colin Gibson, Lisbeth, oil on canvas, 66cm x 56cm, 1943. Image courtesy of Dundee Art Galleries and Museums.

A challenge of a rather different sort had come in 1932 in the form of a commission from the Rowett Agricultural Research Institute, Aberdeen, for a painting to hang in their new Strathcona Hall. Full of symbolism but realistically executed, this huge panel depicts a group of men and women – the ‘Pioneers’ of the title – moving in stately line with their great horses, their cart full of gear and their precious seed corn. There is surely some connection here with the splendid composite red chalk drawing, Man with the Wheel, in which a man strains to move a recalcitrant cart wheel; above, two female figures, swathed in shawls, are bent double, arms outstretched, planting perhaps, or gleaning. Agricultural workers and Angus country scenes also feature in a series of bold ink drawings published in The Arbroath Guide in the late 30s and early 40s. These are generous reproductions, designed to make a big impact on the broadsheet pages, and they are accompanied by musings on the natural rhythms of life and the healing power of nature in these troubled years. A number of these were made into Colin’s first book, aptly titled The New Furrow. Published by T Buncle and Co. of Arbroath in 1938, this volume actually went to the Glasgow Empire Exhibition that year as an example of fine Scottish printing.

Colin Gibson, Man With The Wheel, red chalk on paper, 51cm x 40cm, 1940s

Colin Gibson, The New Furrow, cover, 1938

In the mid-1940s, George Bruce, tired of the strictures of teaching, left to become a producer with the BBC’s Scottish Home Service. This was just the cue my father needed, and he decided to do likewise. Henceforth he would be on his own.

An account book survives of Colin’s early freelance years, and it’s clear that he already had plenty of connections and no shortage of work. One major group of commissions was for large murals to decorate the workers’ canteens at several Dundee jute mills. They only survive in black and white photographs but they must have brought a breath of fresh air to their presumably rather stark and soul-less surroundings. The subjects were some of his own favourites – farming scenes, Highland glens, west-coast seascapes - executed in a bold poster style, using flat areas of colour to exploit the decorative elements in the landscape. The same technique was applied in body colour to a series of covers in the 1940s for The SMT Magazine & Scottish Country Life. He also gained something of a reputation as a painter of local farms, presumably from word of mouth passed around the farming community. These commissions often took him to hitherto unexplored parts of the county and many an Angus farmhouse must have had – and hopefully still has – its ‘portrait’ hanging in pride of place. For these, and for most subsequent landscapes and colour illustrations, he tended to adopt a more ‘traditional’ approach, using a muted watercolour palette of greens, greys, blues and ochres which his clientele probably preferred; in fact, his ‘poster’ phase, like that of his large oils, was fairly short-lived. I, for one, rather regret this: who knows where it might have led? But he was happy to comply; he enjoyed everything he did and was, in fact, a very contented man.

Colin Gibson, At Little Ferry, Loch Fleet, lithographic print, 18 x 20cm, c.1945

Colin Gibson, Sanna Bay, SMT Magazine Cover, September 1945

Black and white illustration work, from the start, was equally in demand. Given his inclinations it comes as a surprise to find his name linked to Modern Marvels of Science (1956), all radio-telescopes and X-ray machines, or Ward Locke’s Red Guides to places such as London, Oxford or Bridport. These he tackled with the utmost professionalism but more to his liking, one imagines, must have been Where the Golden Eagle Soars by Capt. WE Johns (Johns, of ‘Biggles’ fame, was another great lover of the Highlands and they enjoyed some interesting correspondence) or the innumerable drawings he did for magazines such as Gamekeeper and Countryside, Trout and Salmon and The Scots Magazine. His old friend the Arbroath Herald published The Book of the Braemar Gathering and Colin soon became a regular illustrator for this lavish annual production. It was George Bruce, his friend from Dundee High days, who in 1948 had the inspired idea of linking Colin with Seeds in the Wind, the wonderful ‘bairn sangs’ of the Perth poet William Soutar. This delightful anthology of ‘moments of strange imaginings and hours of dreaming’, where puddocks ponder the universe and corbies caw contemptuously at a tattie-bogle, produced a sequence of drawings so vital, and so utterly in tune with the verses, that, as the writer of the introduction claimed, ‘they might well have been conceived by the same person’.

My father never rose – as Soutar did – to the front ranks of the Scottish Literary Renaissance, though, as I’ve already hinted, he did write. What I haven’t explained – and must do so now - is that he regarded himself as a writer as much as an artist: these two aspects of his life go hand in hand and he applied as much care to his prose as to any artistic endeavour. The various magazines mentioned above featured Colin as a contributor of many, many articles and short stories, and he was the author, as well as the illustrator, of the book Highland Deerstalker, the biography of a stalker on the Balmoral Estate. George Bruce, as producer of the radio series Scottish Life and Letters, launched Colin on the entirely new career of radio broadcaster. Throughout the 1950s Colin’s work featured regularly on Scottish and sometimes UK radio, usually as a provider of country notes and pawky tales (for both adults and children, and often very funny). Sometimes he even recorded these in person. There can’t be many people who can claim, as he could, to have had their own illustrations for their own programmes published in Radio Times!

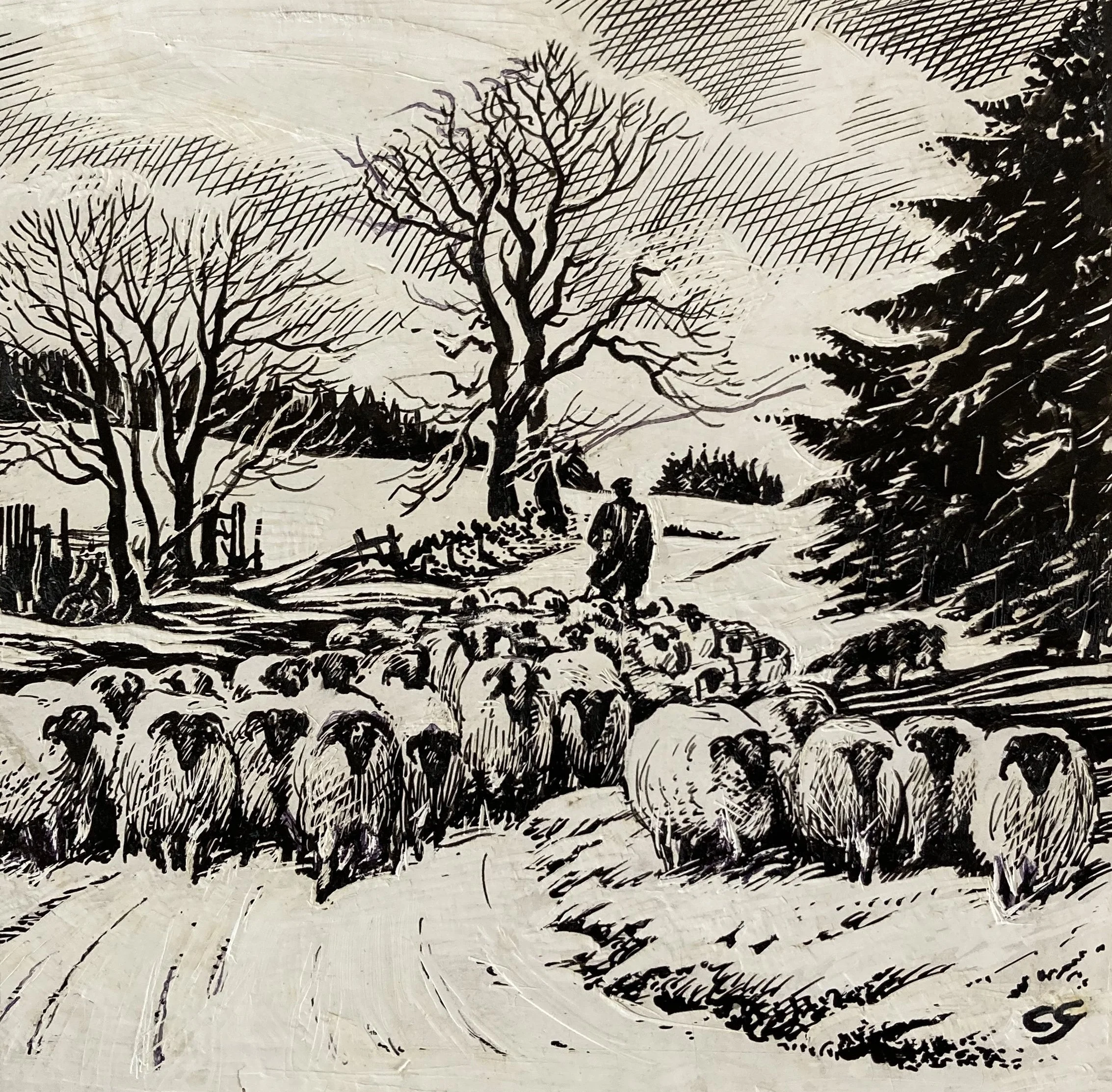

Colin Gibson, Bringing the Flock in, ink on scraperboard, 11cm x 11cm, 1960

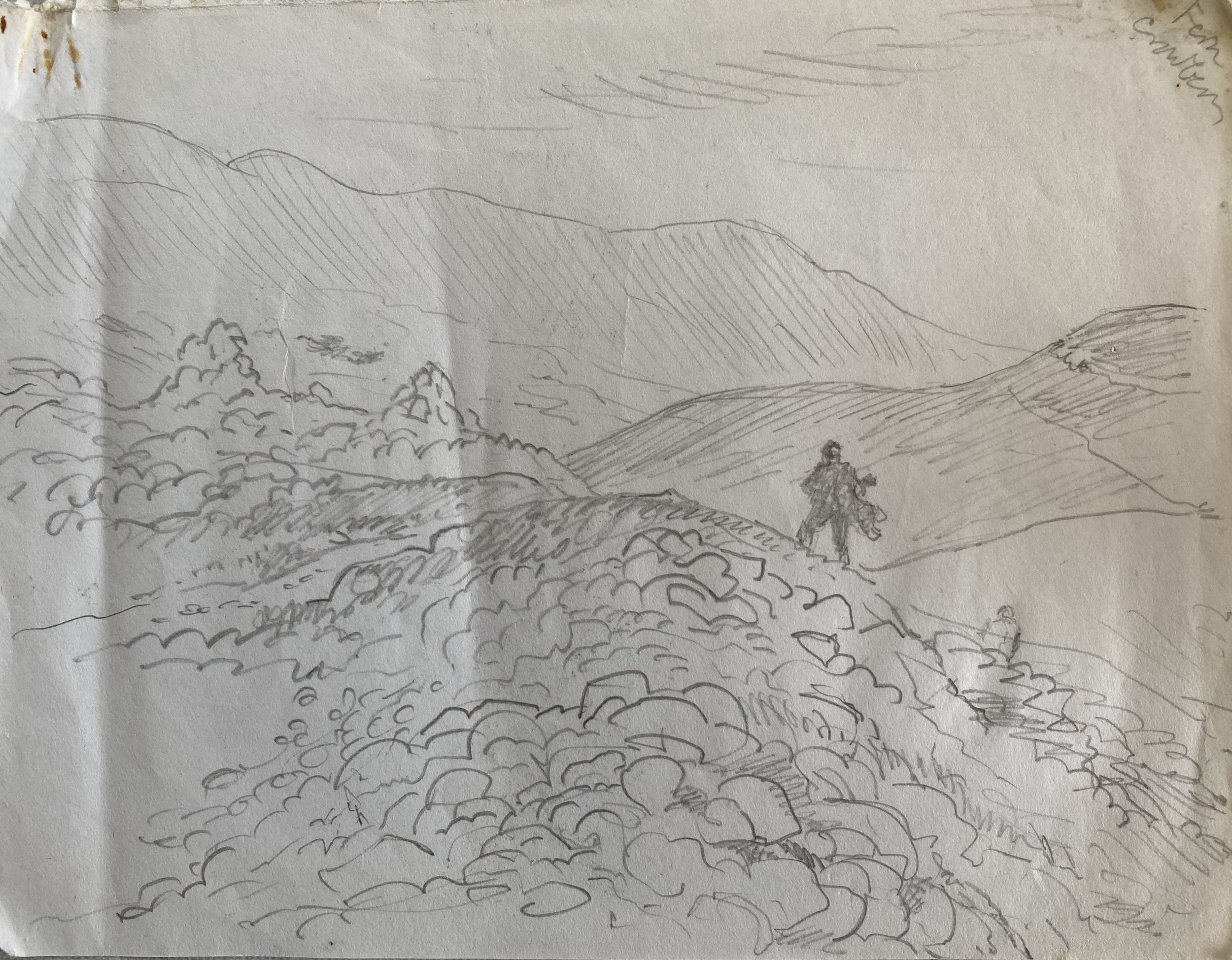

Colin Gibson, Caterthun (sketchbook entry), pencil on paper, 16cm x 21cm, 1964

Colin Gibson, Shepherd and Collies, ink on scraperboard, 18cm x 17cm, 1959 (Note 1)

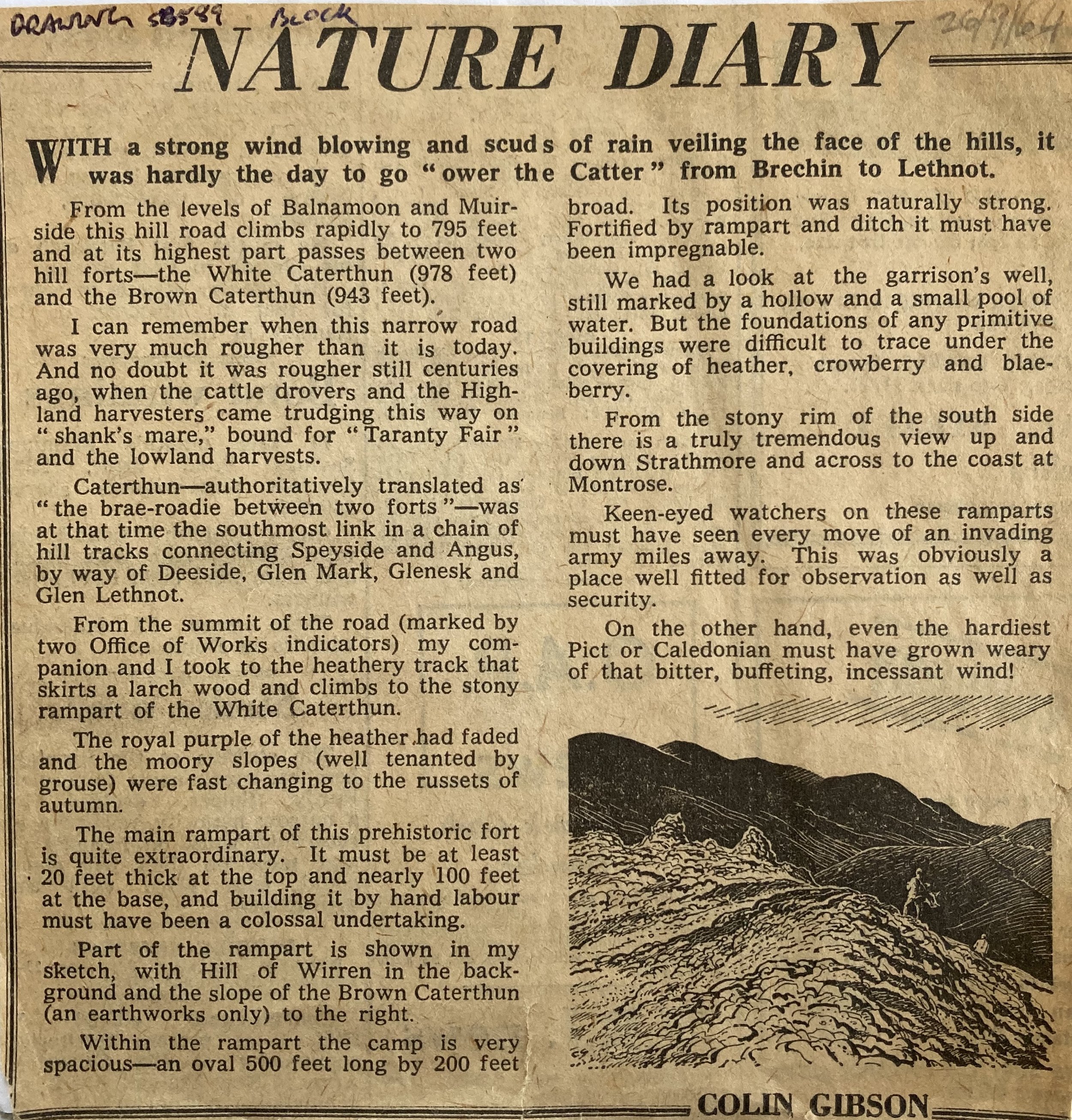

Inevitably, however, a lot of these commissions were ‘one offs’, and Colin must have been pleased when, in 1954, the editor of the Dundee Courier approached him with the offer of a regular slot. His Nature Diary soon became a much-loved part of the Saturday ‘Courier’. The success of the column arose partly from its author’s engaging style, partly from its wide range of subject – the turning of the year, birds, animals and botany, country wisdom, entertaining encounters and the history and folklore of ‘Courier country’ (Dundee University acknowledged this range and depth of knowledge when he was awarded the Honorary Degree of Master of Science in 1979). And, not least, there were the small but beautifully executed ink drawings which always accompanied the text.

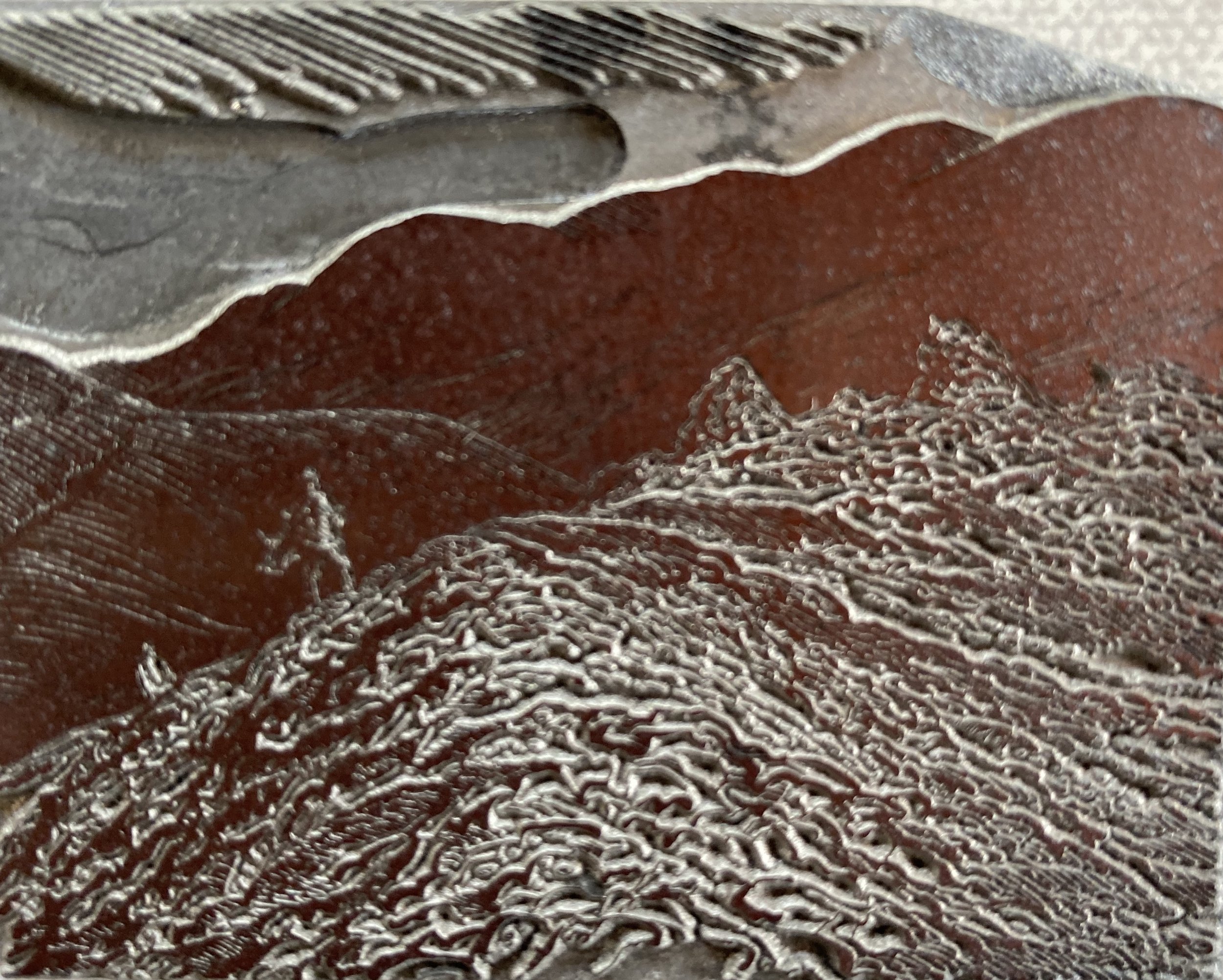

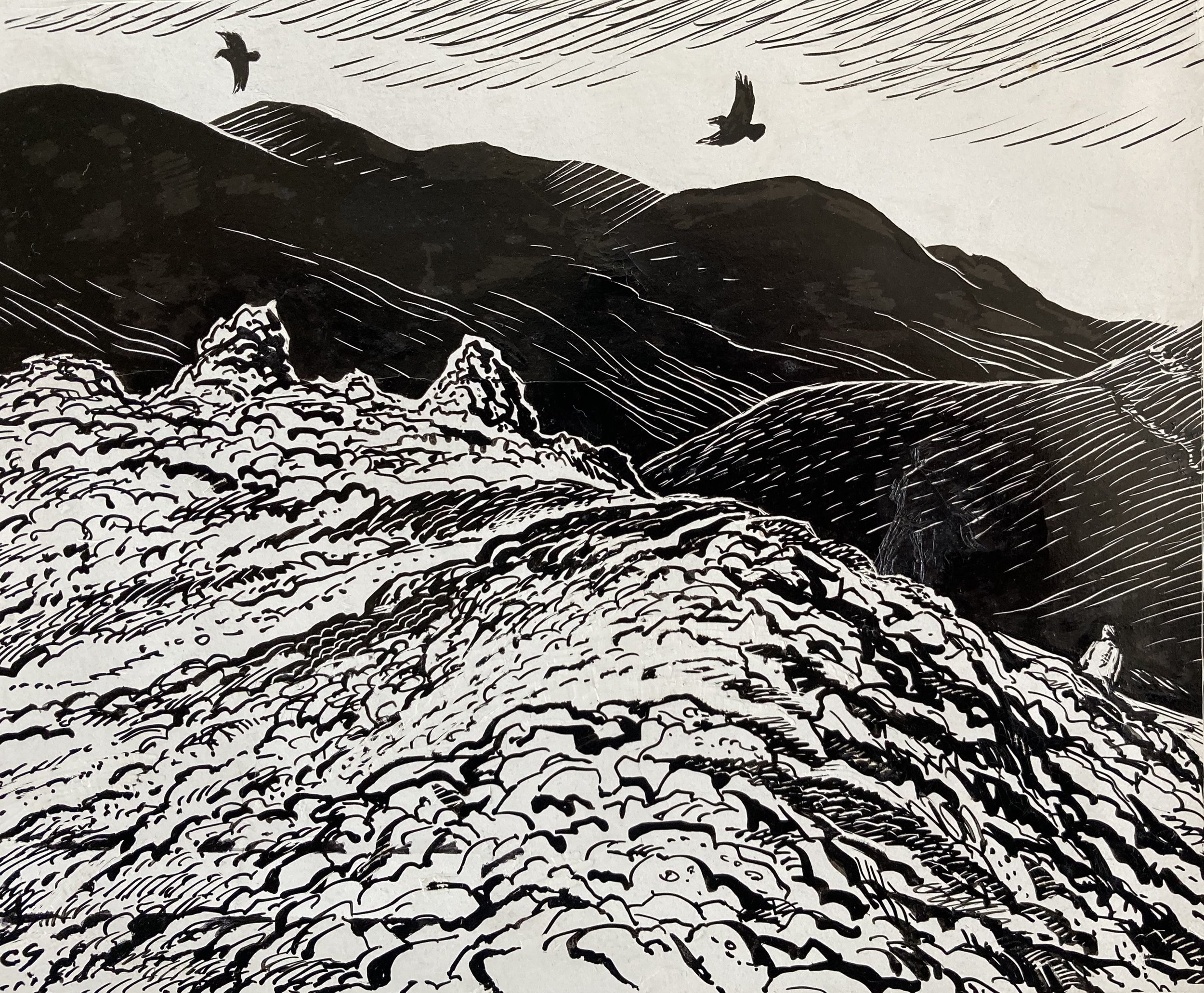

Colin had to think hard about these drawings. He was faced with the challenge of providing an image which had to be reproduced on a square of newsprint which measured some two inches – not the most sympathetic of mediums. His New Furrow drawings for the Arbroath Guide (probably the nearest precedent) had been on stiff paper on a large scale and were often accomplished with bold brush strokes. For Nature Diary he chose to use scraperboard. For those unfamiliar with this medium, it consists of a thin board coated with plaster of Paris; the surface can be left white, or covered with black ink. In the case of black scraperboard, you use a sharp engraving tool, or ‘scraper’, to cut lightly into the black, thus exposing the white beneath. It takes a steady hand to produce a fine line! The effect is fairly formal, rather like a woodcut. On the white version, drawing is done free-hand with a pen (Colin used a fine-nibbed mapping pen) or, for larger areas, with a brush; blacked-in areas can be worked over with the scraping tool to expose the white again, altogether creating a more subtle effect. Colin preferred white, but where it suited the subject he also produced some striking images on the black ground (and yes, he did have a very steady hand and eye). The crucial thing, as far as reproduction was concerned, was that scraperboard produced a very sharp line.

Colin Gibson, Farming Country, Strathmore, ink on scraperboard, 12cm x 15cm, 1976

Colin Gibson, Maggie Gruer, ink on scraperboard, 19cm x 14cm, 1967

The inking-in, however, was only one part of the process. For details of birds, say, or animals, he drew on his collection of reference material combined with his own knowledge. Most Nature Diary drawings, however, began in the field: Colin was always out and about, pad at the ready, and always with an eye to ‘next week’s Nature Diary’. If a subject suggested itself – a landscape, a characterful building, a fine group of trees - it would be drawn with a few deft strokes of a soft pencil. Back home, this would be transferred to the scraperboard either by tracing or by ‘rubbing’. For the latter the drawing would be placed face-down on a blank sheet of paper and the back rubbed vigorously with the blunt end of a pencil to produce an image in reverse. This in turn was placed on the scraperboard and rubbed to produce a further image, the right way round again, which he then inked in. (This process only worked with white scraperboard of course – for black a preliminary drawing would be done in white chalk.) The finished drawing, roughly six inches square, and its accompanying text, would be delivered to The Courier office.

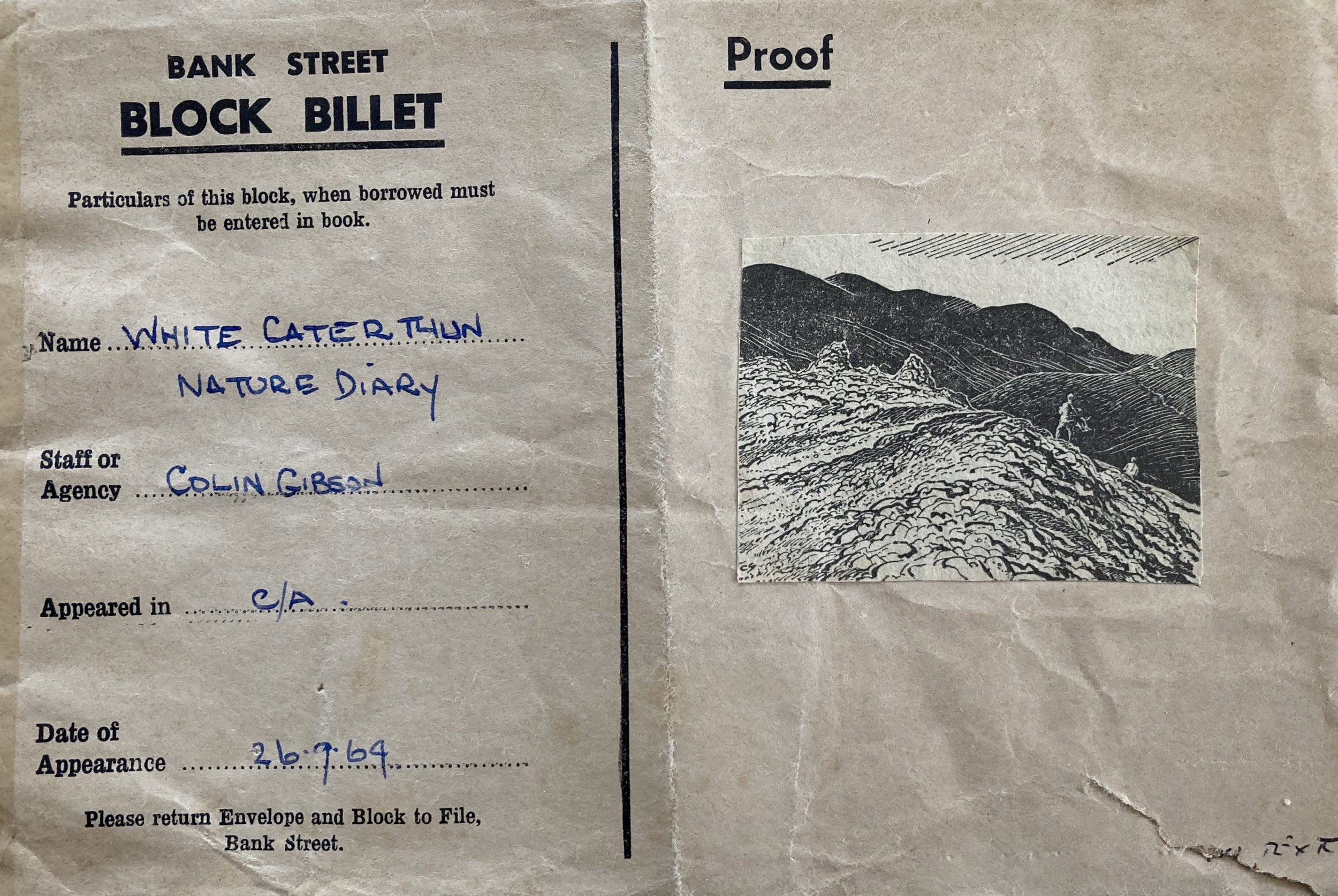

The drawing would be photographically reduced and the image chemically etched – in reverse again - onto a metal printing block. A trial proof was run past the editor, then it would be set into the columns of newsprint and on Saturday – there it was. For all his surviving scraperboards, sketches, cuttings and blocks there remains only a single example of this entire process. It starts with a visit to the White Caterthun hillfort on the braes of Glen Lethnot, North Angus. The original sketch shows part of the great stone rampart, with the Grampians looming beyond. Unusually, the ‘rubbing’ is preserved with this sketch. Then there’s the finished scraperboard, and then the block, contained in a brown envelope with a proof copy pasted to the front and signed off with the editor’s approval; and finally the newspaper cutting, dating from 26th September, 1964.

Colin Gibson, Caterthun, metal plate

Colin Gibson, Caterthun, ink on scraperboard, 16cm x 19cm, 1964

Colin Gibson, Caterthun, editing proof

The Courier Nature Diary, 26th September 1964

One advantage of illustrative work like this was its small scale. When my parents married, they acquired the house in Monifieth which was to remain their home for the rest of their lives. My father simply took over the front room (it was used for entertaining visitors as well – both friends and prospective clients were always fascinated by what was displayed or in process of production). He did, for a while, rent a ‘studio’ above a painter’s workshop in Monifieth High Street and as a small child I used to love visiting this fascinating place with its collections of paint-spattered dust-sheets and old wallpaper and its smell of oil paint and size. No doubt it was useful for dealing with the large canvasses of his earlier days but it was a fairly short-lived venture and he preferred to work at home.

And so he did, winding down but continuing to work (often modifying or reusing existing drawings as his eyesight began to fail) until he died at the age of 90 in 1998. His last Nature Diary was published posthumously: it had run for 44 years.

In spite of the early promise of the Art Society exhibitions and submissions to the RSA, Colin was never really an ‘exhibiting’ artist. He was a member of Dundee Art Society in the 50’s and supported Arbroath Art Society’s exhibitions with occasional offers of existing artworks (some of which, including a fine self-portrait, were acquired for the Gallery collection) but in his later years rarely did any work that wasn’t a regular feature or ‘to order’. His days were already filled with drawing, writing and correspondence and were immensely satisfying. Nonetheless, he was thrilled when, in 1988, Clara Young, Keeper of Art at the McManus, invited him to stage the opening exhibition of the new Art and Nature Gallery at Dundee’s Barrack Street Museum. Colin rose magnificently to the challenge, arranging the return of paintings frae ’a the airts, supplying dozens of scraperboards and other illustrations together with examples of his many publications, and even writing the accompanying booklet. This very popular exhibition saw him reunited with many artworks he hadn’t seen for decades. The latter included some notable commissions, not least a painting of Arbroath’s Abbey Pageant presented by the town to Princess Margaret on the occasion of her wedding and two drawings of the King’s favourite pool on the Dee, given to the then Prince of Wales by the Earl and Countess of Strathmore on his 21st birthday.

Colin Gibson, A Gentleman of the Road, oil on canvas, 53cm x 44cm, c.1928 (Note 2)

Colin Gibson, Untitled, linocut, 19cm x 12cm, 1940s

Colin Gibson, Glenesk Crofter, red chalk on paper, 31cm x 24cm, 1940s

Colin Gibson, Arbirlot Mill, ink on scraperboard, 15cm x 17cm, 1957

I hope my father would also have enjoyed (as I’m sure he would) a number of shows that have taken place after his death. The fiftieth anniversary of Nature Diary in 2004 was marked by a selling exhibition of scraperboards at Eduardo Alessandro Studios in Broughty Ferry, while his centenary (2007) saw a colourful show, A Life in the Landscape, in various venues around Angus as well as the AK Bell Library in Perth. Nor did the publications cease. In the 1960s Dundee Museums had published a set of Nature Diary anthologies, Spring, Summer, Autumn and Winter on Tayside. These had been out of print for years and despite repeated requests for a new collection this had never happened. After his death the requests started coming to me, and as the time seemed right I published two collections, Colin Gibson’s Nature Diary and Colin Gibson’s Nature Diary Volume Two (with over 2000 to choose from, one volume was never going to be enough!). These books are now themselves sold out but Nature Diary drawings lend themselves so well to reproduction (and modern scanners can produce an acceptable image even from a newspaper cutting if the original is lost) that they’ve been used to good effect in several recent publications. These include two delightful books, The Glens of Angus and The Sidlaw Hills, published by Pinkfoot Press, Brechin and written by David Dorward, by happy coincidence a former pupil. Colin would have loved that!

Gillian Zealand

Notes:

The Shepherd was Donald MacLean

The Gentleman of the Road (who is included in photographs of Colin's degree show with a plain background as here) appears in another photo holding what looks like a wide-brimmed hat; this version is entitled The Pavement Artist. Which came first I don't know, but he certainly has no hat here. I suppose it's perfectly possible that a tramp with artistic leanings and a set of chalks could make a bit of cash as a pavement artist in Aberdeen!