Eric Schilsky: Sculptor, Teacher

Eric Schilsky (1898-1974) was a gentle giant of 20th century British sculpture. An exact contemporary of Henry Moore, a Royal Academician in England and Scotland, he was a highly respected portrait sculptor and teacher, first in London then after the war in Edinburgh as the Head of Sculpture at Edinburgh College of Art from 1945 until 1969. Eric was a close friend and colleague of the group of artists now known as The Edinburgh School; his omission from that group to date seems to be because he was a sculptor; he would have been hurt but somehow not surprised.

“I cannot yet get started on any work of my own. I feel quite lost for the time being and barren of any ideas of what I want to do. This state is rather depressing and I feel I ought to begin something… The thought that my colleagues are waiting for me to begin something so that they can see my capabilities is a most paralysing thing to me, but I shall have to begin some day. Everything here is so strange to me and my whole life in this city has no roots, it's like having to begin all over again…

The Scots are a strange people and I am definitely a foreigner, and as such a little suspect. Probably the fact that I have a Polish name makes me doubly so, the Poles here being rather unpopular at the moment. I knew the beginning would be difficult for me and I must give it a little time before coming to any conclusions…

The houses are of stone and they go nearly black in colour which I don't like at all… When the weather is really fine it's not quite so bad but when the sky is grey, Edinburgh has such a dismal and drab appearance, which is entirely due I think to the complete lack of colour… I don't know if I shall ever get to understand the Scots, their nationalism just irritates me beyond words.”

So wrote Eric Schilsky the sculptor to his future wife, the painter Victorine Foot, on 11th October 1945. He had just moved from London to Edinburgh to take up his new teaching post as Head of the School of Sculpture at The Edinburgh College of Art (ECA).

Born in Southampton on 28th October 1898, Eric’s father Charles was a professional violinist of Polish descent; his mother was English with French roots. She committed suicide when Eric was six and his brother Trevor was eight. After this, their father struggled to combine frequent travel to his many work commitments with providing a stable home for his boys. Boarding school was inevitable and not a success; so it is likely that their Uncle Edouard in Paris, also a gifted musician, was influential in the decision to look at options abroad. In 1913 Charles enrolled both boys at The École de Beaux Arts in Geneva where Eric’s artistic education began, accompanied by his stepmother, Louise, and Trevor, his brother.

Eric completed a year of foundation courses in Geneva which included Modelling with James Vibert, the Swiss sculptor who had spent four years in Rodin’s studio.[1] He was unable to begin his second year in 1914 as the Schilskys decided to return to London when war broke out. Eric enrolled to study sculpture at The Slade in 1914 under James Havard Thomas. His tuition was firmly rooted in the classical tradition which gave Eric his lifelong passion for the study of form and Ancient Greek sculpture. The war interrupted his studies; Eric was sent to Palestine with the Gloucestershire Yeomanry but, he told his sons, only experienced discomfort, inadequate training and mismanagement, returning safely to resume his studies in 1918.

At this date, The Slade regarded the French sculptural tradition with suspicion. But nor did it embrace new ideas: as Eric’s student Kevan Coultan summarised: “In 1917 Rodin died, a puzzling and largely misunderstood giant; Brancusi was just beginning to hack away at the weeds that had grown on European sculpture; the young Epstein was launched on a sea of controversy; Maillol's career was hardly gaining ground; Moore was exactly Schilsky's age and many of whom we now regard as major figures were not yet born. Schilsky witnessed the growth of Cubism, Futurism, Constructivism, Abstract Expressionism and many other schools of thought. Even Pop Art was born before Schilsky died. Figurative art, in the face of such revolutionary tendencies, became an increasingly lonely pursuit and one which required an extraordinary single-mindedness.”[2]

Fortunately, Eric had the necessary focus and his talent was recognised early; he was only 25 when three of his portrait sculptures were selected for the 1923 Summer Exhibition at the Royal Academy and singled out for favourable press reviews. These were a head of his uncle, Edouard Schilsky, and a bust, “The Musician”, together with a head of his friend (and flatmate of his brother Trevor) the artist Adrian Allinson, “portrayed in the manner of a Byzantine Christ.”[3]

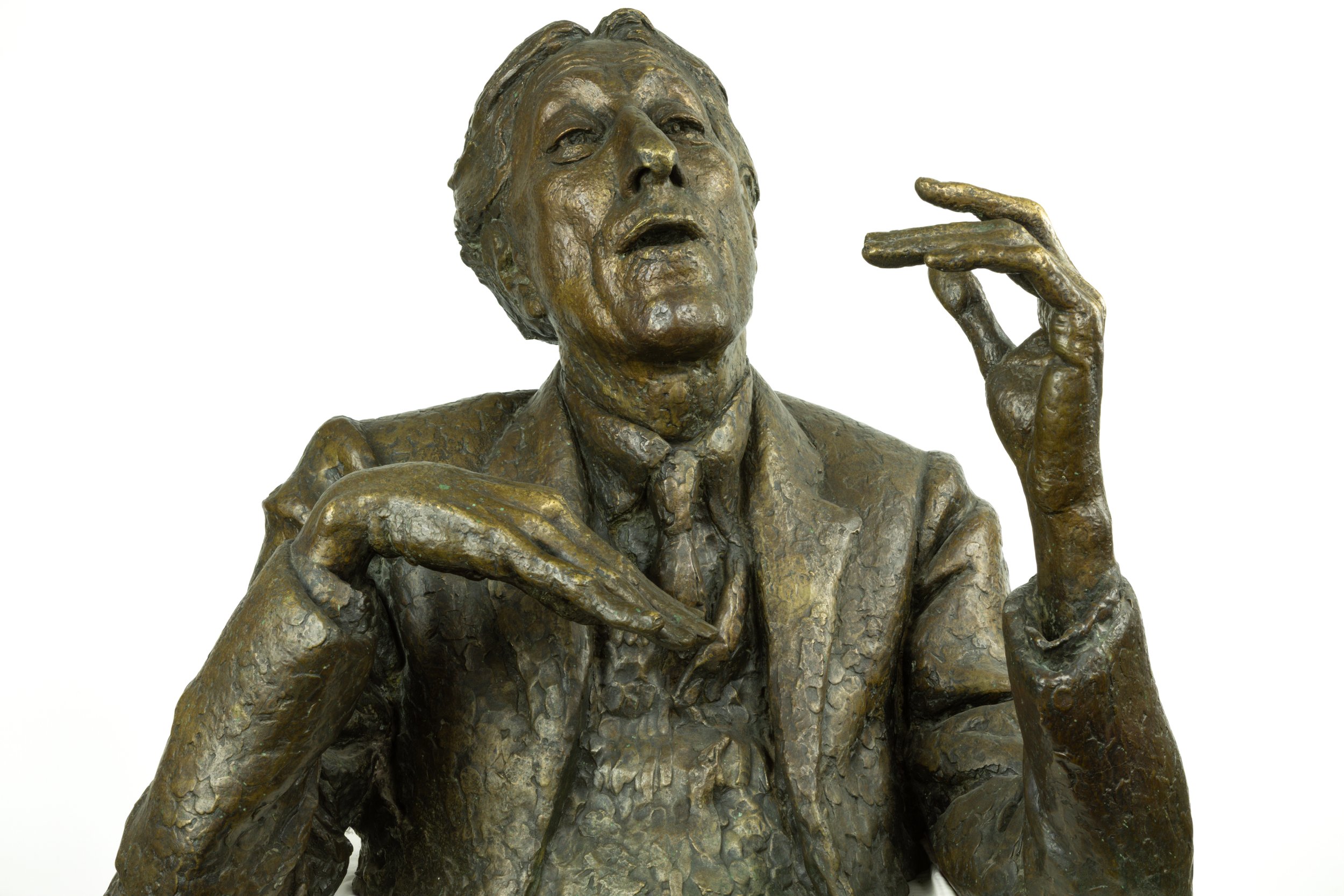

“The Musician” is also a portrait of Edouard, here in full flow, his hands gesticulating excitedly, his head thrown back. The bronze is vibrant, and animated, it captures the long, pianist’s fingers of Eric’s uncle whose talent rivalled that of Delius.[4]

Eric Schilsky. The Musician. c.1920. Bronze. 58 x 60 x 32cm. Private collection.

“This work was much admired by Schilsky's friend, the painter, Walter Richard Sickert, who presented the gallery that showed his work with an ultimatum - he would only show a particular painting (his portrait of the actress Gwen Ffrangcon-Davies) if it were accompanied by this bust. Incidentally, in later years Schilsky would relate, with great humour, his memories of the highly colourful and eccentric Sickert”.[5]

Inspired by the bust, Sickert decided to carry out a joint project with Eric - a study of Gwen Ffrangcon-Davies’ hands. By 1926, Eric had begun her portrait but this was not completed[6] and only Sickert’s painting of the actress survives. Eric did, however, model a striking bust of Ernest Thesiger, now in the V&A, with which the actor was very pleased.[7] Both were friends of Eric’s brother, now Austin Trevor, a successful actor on the London stage.

Eric exhibited “The Musician” many times throughout his career and Victorine recalled him wanting to recapture some of this early energy in his later works. But just as Maillol rejected the vigorous modelling of Rodin, Eric later moved away from expressionism, seeking serenity and stillness in his portraiture.

Eric’s twenties in 1920s London were productive, exciting times for the young sculptor even if, as his close friend and confidante, the author Stella Gibbons recalled, he had no money and at times survived on coffee and biscuits.[8] He taught evening classes at the Westminster School of Art and worked and slept in the mezzanine floor of a studio in Queen’s Road (now Queen’s Grove), Marylebone. He shared the space with the painter Mabel Greenberg, a fellow student at the Slade; she introduced Eric to Sickert. His circle also included Clara Klinghoffer, Bernard Meninsky, Mark Gertler, John Farleigh, Stephen Bone and later Mervyn Peake and Maeve Gilmore. He presumably knew of and visited the Omega Workshops since the model for his first female bust was their dress designer and seamstress, Gabrielle Soëne, who was also painted by Roger Fry and Edward Wolfe and modelled for Epstein in 1917-18.[9] The two busts illustrate Epstein and Schilsky’s contrasting approaches to portraiture; Epstein posed “Gabrielle” looking upwards, her eyes searching, she appears tense, whereas Schilsky draws her with eyes cast down, she is serene, modest; perhaps she is sewing.

Eric Schilsky. Gabrielle Soëne. Bronze. c.1918 and 1974. 53 x 41 x 18cm. Private collection (also in the collection of the National Galleries of Scotland).

Eric’s daughter Chiara observed that he promoted his female portraits to “Goddess” with an idealised beauty and over his lifetime, Eric became increasingly concerned with capturing this ideal. Though bronze, there is a softness, a vulnerability, and these portraits are always intimate. His men look out at us, they engage, they are talking or listening, his modelling and surface finishing is deeper, they catch and throw back the light. In contrast, the women often have their eyes cast down, Madonna-like, or they look past us, lost in thought; they are smoother, refined, gently tooled, the light reflects from the surface giving them a glow - or is it a halo?

In his early work, Eric liked to explore where best to stop with the figure, sometimes he includes the hands or half the legs; he truncates the shoulders, setting up an interplay of forms with voids between the limbs which builds on his training in classical sculpture, particularly those of the Archaic Greeks. His portrait; “Indian Woman”, executed before 1922 (exhibited at the RA in 1924) was received as “an original portrait showing scholarship’s skill, refinement of taste and reserve.”[10] The pose with hands clasped in her lap and the truncated legs echoes Městrović’s “Portrait of The Sculptor’s Mother” which was exhibited at the V&A in 1915 and illustrated in The Burlington Magazine of the same year.

According to Chiara, Eric was an agnostic. Though never a practising Jew, his sons remembered that he would not tolerate anti-Semitic remarks, understandable given his family heritage. He lived in West Hampstead among a close circle of Jewish friends and colleagues. Herbert Marks, a wealthy North London accountant, became an important patron and friend, probably through Stella Gibbons. Herbert Marks had married Stella’s best friend, Ida Affleck Graves, the poet and he was “very Jewish and starving for culture” according to Ida.[11]He commissioned a bust of himself in 1922, which, like that of Ernest Thesiger, references Bourdelle in its strong modelling, the tilt of the head and squared-off shoulders.

Eric Schilsky. Herbert Marks. 1922. Plaster with black finish. 56 x 27 x 36cm. Private collection.

Bourdelle exhibited his bronzes at the Grafton Galleries in 1921 and the RA in 1922 and although there is no record of Eric attending classes at the Académie de la Grande Chaumiere, he often travelled to Paris to visit relatives and he later spoke of artists he met in Montparnasse. Like Bourdelle, Eric’s preferred technique was modelling slowly and painstakingly in clay and/or plaster; he rejected direct carving after a flirtation with abstraction in his bold portrait, “Earl Beatty”, in stone. Eric exhibited this bust with The New Autumn Group and The Studio gave it a full page illustration in 1926.[12] But it had attracted this harsh criticism when exhibited at the RA in May 1925: “Accentuation of planes is carried to an extreme in Mr Schilsky’s bust of Earl Beatty, which may be almost described as a stylised copy of Epstein’s well-known bust of Lord Fisher.”[13] Eric later destroyed the work, telling his son it had been too heavy to move to Scotland.

Eric Schilsky. Earl Beatty. 1925. Stone. Lifesize. Work destroyed by artist; pictured in The Studio, 1926.

Comparisons with Epstein were inevitable as Eric took the path of portrait sculpture, taking commissions for heads of children, and twice working from the same models (Gabrielle Soëne and Eileen Mayo). Press reviews sometimes referred to Eric as “a disciple” and “a follower” and once “a copyist” of Epstein. He was in Epstein’s shadow: “Schilsky’s… skilled and limpid” forms “ably support” the “superb” Epstein. Another reviewer contrasted the “hectic” quality of the Epstein to the “sensitive” busts Eric had submitted. It must have been frustrating, but Eric was controlled. In 1945 Eric saw Epstein’s “Lucifer” and wrote to Victorine:

“I always feel his bronze statues are portrait heads that he has decided to add to as an afterthought. I’m afraid the quality of Jewish theatricality is too prevalent for my taste. (This is not ant-semitism). It’s just a fact. I am more and more of the opinion that sculpture should be quiet and definitely not theatrical.”[14]

However, Eric always maximised the sculptural richness offered by an exuberant head of hair, perhaps because he had one himself. Herbert Marks commissioned heads of his first two children; “Anna” (aged 2) was exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1924 and her brother “David Anthony” in 1925. Anna has rolling, tactile curls and he gave William Gillies’ shock of white hair a similar expressionist treatment in 1956 (see illustrations 4 and 12). Portrait heads of children were a popular commission and Eric’s were kind, but (in the eyes of most critics) he avoided sentimentality and so received many commissions throughout his career. “Anna”, one of his first, was around the same age as Eric’s first son René, born in 1923 to a model, Phyllis Ibbetson. They did not marry, perhaps because Eric had begun a passionate affair with Ida Affleck Graves whose marriage to Herbert Marks was not a success, but Ida would not risk losing her children to be with Eric. Around the same time, Eric met Bettina Raymond-Cox whose husband commissioned a bust of her, and once again fell in love, his emotions entangled with his work.

Eric Schilsky. Anna. Bronze. 1924. 24 x 15 x 25 cm. Private collection.

Bettina Fenton was striking; she made her own flowing dresses in lengths of rich, exotic fabric. She trained as a painter at the St John’s Wood School of Art in the same year group as Gluck, by whom she was painted twice[15]. Like Gluck, Bettina came from wealthy North London Jewish parents, who had settled in Britain from Germany; they changed their name from Fleischmann during the First War. The family was passionate about the arts; her father collected Mayan ceramics, her brother was a close friend of Aldous Huxley[16] and Eric’s son René remembered that Bettina supported Charles Laughton, the actor, early in his career as she had an income from family coffee plantations in Guatemala.[17]

Bettina married Alan Raymond-Cox, a Harley Street doctor, in 1922 but fell in love with Eric while posing for her portrait and they began an affair. She moved to a small flat in Abbey Road where Eric’s son Ronald was born in 1928. Eric was named in the divorce case of 1929 after which he and Bettina were married.[18] They made a home for Eric’s two sons in a large flat in Compayne Gardens, West Hampstead, where he moved his studio in the early 1930s. He carried out several sensitive portrait studies of his boys in clay, plaster and bronze including Ronald Asleep (exhibited at the RA in 1938).

Eric Schilsky. Ronald Asleep. Bronze. 1933. 31 x 48 x 63 cm. Private collection.

The lean years of the 1930s brought fewer private commissions but Eric was fortunate to be given more teaching hours at the Westminster School of Art and talented students including Maeve Gilmore, Eileen Mayo, Jean Appleton and John Craxton. He found he loved teaching and with limited space at home, he worked alongside his students. The illustrator Susan Einzig, interviewed by Chiara in 2004, remembered Eric’s life class and his help starting her off in wood carving at the Central School in 1939, just before it was evacuated to Northampton. One of Eric’s few figures in wood, “Flora” dates from the 1930s. The school’s model Olive Clark inspired the head “Héloïse” of 1936 which he later submitted to The Royal Academy in 1968 as his Diploma Work.

Eric Schilsky. Héloïse. 1936. Bronze, here with green patina (500mm). 41 x 28 x 24cm. Private collection (also in the collection of the Royal Academy).

News from Europe was increasingly bleak, particularly for the London Jewish community. Eric’s father died and he was deeply affected by the additional shocks of Mark Gertler’s suicide, the mental illness of Mervyn Peake, and the illness and early death of Mabel Greenberg. The Fentons lost their coffee plantations so Bettina also had to find work. She suffered from anxiety and became concerned about Eric’s fidelity; she would monitor him, sometimes sitting in on his classes. Eric’s poignant bronze bust “Bettina” of 1936 and the Italianate plaster head and shoulders from 1940 hint at her vulnerability and sadness.

Eric Schilsky. Bettina. c.1940. Plaster. 45 x 41 x 23 cm. Private collection.

Following the outbreak of World War II, Eric and a group of around sixty other artists were employed by the Ministry of Home Security at the Civil Defence Camouflage Establishment in Leamington Spa to develop camouflage schemes for naval ships, factories, airfields and other military targets. They were based at the town’s ice-skating rink (The Rink) and in other public buildings where they worked long shifts after which they partied. Some artists brought their wives and these couplings rearranged themselves over the five years spent at the Unit. The artists were billeted in the “pleasant, but mildly dilapidated spa town’s” summer lodging houses amid the raised eyebrows of fierce landladies.[19]

Eric went to Leamington Spa from North London in 1940 and Bettina arrived a few months later after dispatching their 12-year-old son Ronald to wealthy friends in the United States for the duration of the war. Fortunately, Ronald adapted well to his new life in safety and comfort but Bettina was lonely and under-occupied in their small digs without him and a long way from her family and friends in London. She was often alone at night as the artists were obliged to fire-watch on the roof of The Rink in case of air raids. Her anxiety became overwhelming. Eric encouraged her to continue drawing and painting but his invitation to the much younger painter, Victorine Foot, to pose for them naked at their flat contributed to her deep depression and just a few weeks later, in February 1943, she took her own life using their single gas ring.[20]

Bettina’s suicide came as a huge shock to both Eric and Victorine. Victorine’s chatty, daily journal ends at this point. They were propelled together by the tragedy, taking comfort in each other’s company and quickly falling in love, but both experienced overwhelming struggles with guilt. A devout Christian Scientist, Victorine left Leamington for a few months. She attended the surgery of Eric’s Harley Street doctor who would later treat him for severe depression in 1945. They wrote daily when they were apart, and Victorine kept all of Eric’s letters, which were often in French (although he did not keep hers). These now form part of the couple’s remarkable archive which their daughter Chiara Schilska curates. It documents their passionate, supportive and respectful relationship.

Victorine Foot, also a painter, was 22 years younger than Eric and had not yet completed her diploma. Her war service over, she returned to the Central School in 1945 and looked for London lodgings with young Leamington Spa friends who were also restarting their studies. There were no openings for Eric in the London Schools in 1945 so he interviewed for a job at Edinburgh College of Art in June, accompanied by professional and character references, including from his close friend and colleague Bernard Meninsky:

“It gives me the greatest possible pleasure to write this testimonial on behalf of Mr Eric Schilsky. He was my colleague for many years at the Westminster School of Art, and also at the Central School, in London. I know him to be an inspiring teacher in the art of sculpture. Mr Schilsky stressed the great importance of drawing to his sculpture students. For this purpose, several of them worked in my life class… Mr Schilsky imparted to his students the same high ideals in sculpture which I know he holds himself. This resulted in their producing modelling and carving of a very high standard - serious, studied, coming to close grips with nature, yet modified by an understanding of the plastic necessities inherent in sculpture.

His students’ enthusiasm for Mr Schilsky’s teaching was fully justified by the highly interesting and able work they produced under his supervision.

In his own creative work, I know Mr Schilsky to be a very fine craftsman - his understanding of this side of his art is very thorough. His aesthetic ideals are of the very highest, as is his scholarship in all great periods of sculpture.

With these qualifications, Mr Schilsky would always justify an appointment to a position of responsibility in a School of Sculpture”[21] (Oxford, 13th April 1945).

The Edinburgh College of Art Board appointed Eric as a part-time Head of the Sculpture School for three years, on a salary of £700 per year plus a war bonus. The Board minutes record the struggles Eric experienced over the following 25 years to achieve parity in salary and conditions with the Head of Drawing and Painting, which he only achieved just before his retirement in 1969.[22]

Eric wrote to Victorine in November 1945: “Today I have just completed my first month here, and as I review it I wonder how much of a success I am going to make of the job. I am beginning to feel a little less strange but there have been awful moments of doubt and strain and delicate adjustments to make. Still, I'm going to have a good shot at making something of it and must give it a fair trial…

“I am in a quandary. I might be able to get a studio here, it belongs to a man named Blakemore (sic) who married a girl who was a sculpture student here before the war, they are now living in London and he is up in Edinburgh till tonight. I went to look over the studio this morning. It is a very good one, spacious, with the top lighting of a proper sculptor's studio with a big sliding door on ground level. The rent may be in the neighbourhood of £50 per annum which compared to the London prices is cheap, but for Edinburgh I understand it is expensive, it has a little kitchen and a lavatory but it is not strictly residential. He is not certain whether he wants to let or sell. I told him I would think it over and let him know. There are several cons; for instance heating the place in winter when one is not there the whole time and additional expenses of coal, gas and electricity which would probably bring the rent up to £75 per annum at least. There is no bath at all and the rates are not for living premises. I don't feel really justified in this expenditure although it would be nice to have a place of one's own.

You see if I thought I was going to stay in Edinburgh for the rest of my life it would be different but to bring all my stuff up from Leamington and London for 3 years at the most…”[23]

This would prove to be a turning point. Eric had been allocated a studio at ECA but preferred a private space to live and work on sculpture commissions, as in London. He had been working sporadically on two portrait heads of children, Andrew Fairbairn (exhibited at the RA in 1947) and Simon Greenway (exhibited at the RA 1948) but his slow and painstaking working methods required space and time outside teaching hours. This top-lit studio in Marchmont, a short walk across the Meadows from the College, was built around 1886 and belonged to the painter Patrick William Adam until 1908 when the painter George Smith moved in, then the stained glass artist Charles Blakeman who taught at ECA and his wife bought it in 1934.

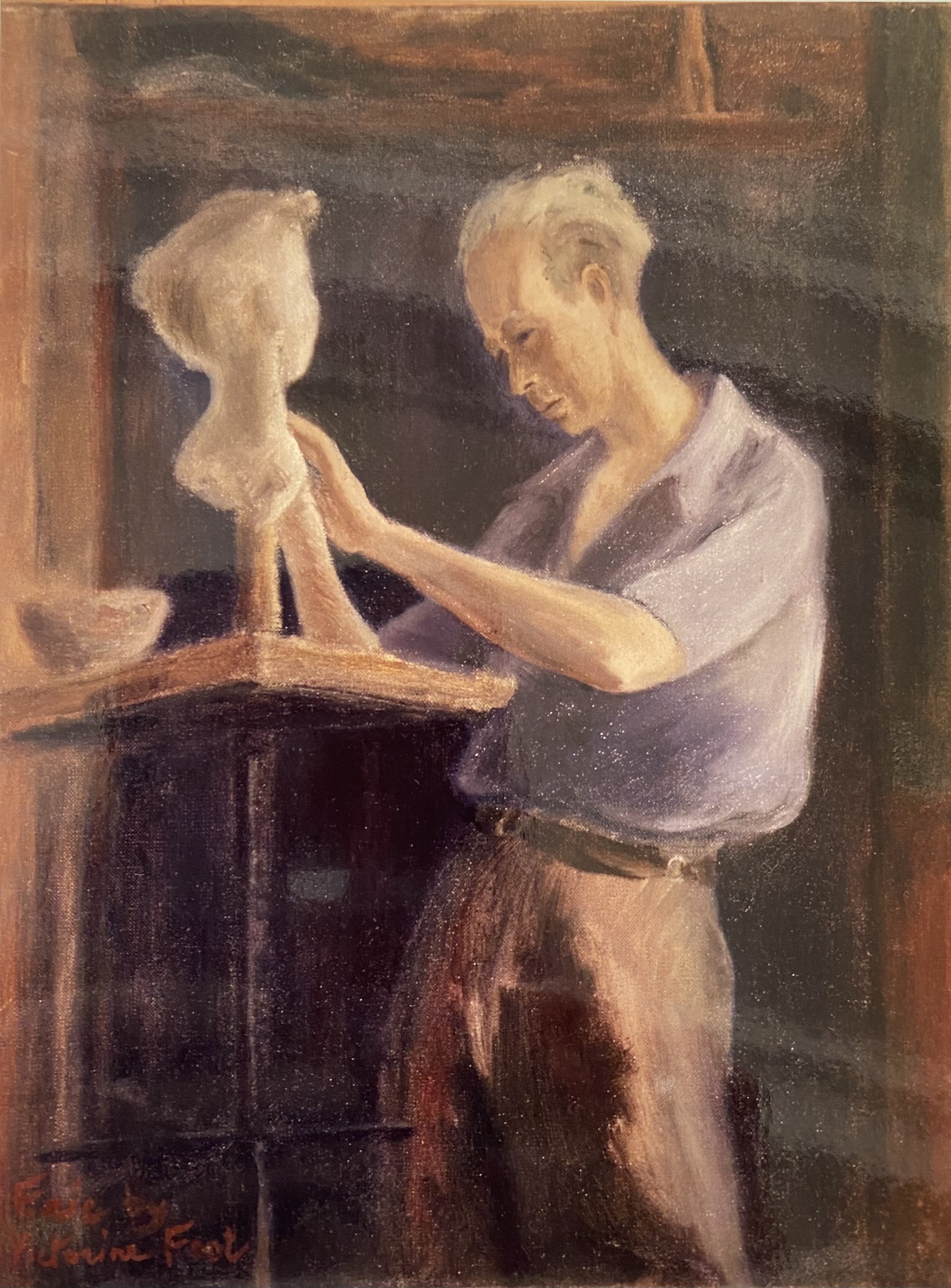

Victorine Foot. Eric Working in his Studio. c.1950. Oil on board. Dimensions unknown. Private collection.

Victorine and Eric’s 1945 correspondence ends in December when they were reunited in London. They decided to marry after Christmas, in Chelsea, on 5th January 1946 and Victorine moved north to be with him. At first they rented a flat in Grange Loan while negotiating the purchase of the studio in Victorine’s name for £640 in September 1946. They made simple changes so they could live there, and then Eric’s friend, the architect Alan Reiach, adapted it further with bedrooms upstairs. Chiara was born there in 1951. Eric completed a head of the infant John Reiach, Alan Reiach’s son, in 1952 (exhibited at the RA in 1959).

Eric and Victorine found they enjoyed life together in Edinburgh. It was a fresh start, there were no ghosts, although they made regular train journeys to London to see family, an annual visit to the RA exhibition, and Eric became an external examiner at the Royal College of Art. Victorine completed her Diploma at ECA, graduating in 1948 and later, when Chiara went to school, she became an art teacher at Oxenfoord School while continuing to paint and exhibit. The Schilskys made firm, life-long friends with the artists now referred to as The Edinburgh School but they are never mentioned as part of this circle. Chiara remembers Eric and Victorine’s frequent hospitality:

“We had music evenings with Joan Dixon the cellist, Anne Redpath, Bill Gillies, Willy McTaggart, and Fanny McTaggart (Aavatsmark), who were all part of the circle. He (Eric) was very sociable. So you have this other side to him, where he loved to have people round and talk art. They talked art all the time. As a child, I thought ‘my God, they don't talk about anything else’. Michael Snowdon and Vincent Butler, Kevan Coultan, Chris Hall, they were around all the time. He (Eric) was very generous with his place, and he nurtured people… then there were the parties, where they had to join two tables together there were so many people.

“I remember too the frequenting of countless private views, the tipsy and jocular artists in fancy dress at The Edinburgh College of Art Revels, evening drinks parties, Sunday trips to the seaside with Gillies, Maxwell, the Cooks or the Clarkes. Gillies with his pipe, smoke swirling, tinting with golden nicotine his wavy white curls and fingers, his kindly manner and inimitable sense of humour.” [24]

Victorine’s portrait of Anne Redpath (exhibited at the RSA in 1972) was drawn from a photograph of Redpath taken sitting at the Schilskys’ dinner table. Other close friends were Robin Philipson and his wife Diana who reminisced with Chiara in 2003 and me in 2020 about her visits to the studio and memories of Eric at ECA in the 1950s:

“He had an aristocratic air about him, he was such a gentleman, he was very courteous, he'd open the door for you and let you go first, really old fashioned manners, not something you came across very often. He was a very, very striking person and he stood out amongst men… he had such a wonderful presence. He always had time for one, one always felt, he wasn't in a hurry, he just lived in a different era.”

After the bleak wartime years and uncertainties of a new start, Eric was again productive and receiving commissions. 1956 brought long-awaited recognition; he was elected an Associate of the Royal Scottish Academy, submitting the head “Tamar” as his Diploma Work,[25] and in 1958 his busts “Bettina” and “Mabel” (Greenberg) were exhibited there alongside Jacob Epstein’s “Girl with Gardenias” in “the best sculpture show for several years” according to the press review.[26] Eric was also elected an Associate of the Royal Academy in 1956 and exhibited three works there in 1957, a celebration of his new life in Scotland: a portrait head of his toddler daughter, “Clare”, another of his great friend, William Gillies and a bust “Cecilia”, this last a sensual portrait of his ECA model Cecilia Kerr.

Eric Schilsky. Tamar. 1956. Bronze. 38 x 18 x 27cm. Private collection (also in the Diploma Collection of the Royal Scottish Academy).

Eric worked with another ECA model for “Patricia” which was shown at the RSA in 1951, and purchased by the RSA via the Chantrey Bequest in 1974. For Kevan Coultan, this was the best of Eric’s portraits: “the most perfect example of his ability to synthesise life into sculptural terms, which in themselves have life and warmth. Its great strength lies in its passivity.” (see link below to an illustration on the RSA website).[27] Eric worked on the maquette again in 1974 and recast her wearing a hat he had found lying in his studio.

In the late 1990s and early 2000s Chiara contacted many of Eric’s former ECA colleagues and students to learn about her father’s working methods and teaching. When possible, she recorded and transcribed interviews. She also wrote numerous letters and the replies form part of her rich archive to which she has generously given me access and permissions. Dave Cohen was a Professor of Ceramics at ECA from 1965 until 1985 when he became Head of Ceramics in Glasgow. He had begun his career as a welder in the US Navy.[28] He recalled his experience of Schilsky’s teaching in an interview with Chiara Schilska and Andrew Brown in October in 1998:

“It was a very, very classical education in the sense that Eric was the Master and he knew the figure and that is what he taught. He didn’t indulge in Abstract Expressionism or Conceptual Art or things like that because it wasn’t part of him. The whole staff were basically classical sculptors; Ann Henderson, Norman Forrest and Andrew Dodds. They were all figurative sculptors. We had a few rebels in the crowd… but basically, everybody conformed to the teaching of the figure… Eric took us for the life figure, especially in the fifth year”.

“We had to do an antique carving, which nowadays would be totally irrelevant. And that’s the classical education… that was put together by Eric and from 9.30 until 4 o’clock that’s what you did, if you wanted to do anything else after that, that was fine, he didn’t mind. When he was teaching it was about the figure. By the time were got to the fifth year… you spent three days a week doing life modelling, from a model, either Carol or if we didn’t have Carol there was another girl there who was very, very petite and very, very difficult because she was so beautifully proportioned (this was Cecilia Kerr, Eric’s model for a bust and a statuette: The Adolescent 1959)”.

Eric Schilsky. The Adolescent. 1959. Bronze. 43 x 18 x 10cm. Private collection (also in the collection of the City Art Centre, formerly the Scottish Arts Council collection).

Eric regarded the sculptures of the Parthenon as “an absolute peak in the history of sculpture” and returned to them again and again in his teaching. This was easy to do as the ECA cast collection contains 79 panels from the Parthenon Frieze displayed around the Sculpture Court (which was built to house them in 1910), together with 71 other casts from the antique. He did not visit the Parthenon until 1972 when he was invited to address the staff and students of the Academy Schools in Athens on Greek Classical Form. His transcript survives; for Eric, the building blocks of a sculptor’s “shape language” were the cylinder, the cube and the sphere, and he defines sculpture as “the expression of man’s emotions and spiritual aspirations conveyed by and externalised into the language of form in a concrete medium.”

Dave Cohen again: “Eric, when he taught, he taught like you were the apprentice in a sense, it was like you would go on so far on a figure and then he would come up and virtually work on the figure… instead of talking to you, he actually showed you, and that is something that is completely away in this day and age. Nobody on the staff can actually roll up their sleeves and actually show you about processes; if there any processes to be done you are sent down to the technician and they will spend hours and hours talking to you, but there are very few, if any, and I don’t know of any, except if Mike Snowden was there, or somebody who could actually show you the difference and explain the difference by actually doing it; that was Eric’s strong point... I think I was the only person who actually finished the antique. I did a little boy’s head by Donatello, a beautiful wee thing, and I worked on it and worked on it and worked on it and I didn’t appreciate what I was doing until I got to about a millimetre away from the surface, and then you started to actually find out, experience what the carving was all about. Up to that time, you are just knocking off big pieces but when you get down to the quality of the work, then you really have to study, and this relationship of Eric working on the figure and me copying the antique, it was the same sort of relationship.”

“His one comment all the time would come out in the teaching (here Dave Cohen lowers his voice and gives a taste of Eric’s vocal delivery, whispered with great import and an exciting air of suspense…) “The form has got to look like it is pushing from the inside outwards!”

“He loved Aristide Maillol, if you take any of Maillol’s figures which are lying down and you take those rhythms and you analyse where the arm is placed and how close it was to the body and so forth, it wasn’t by chance… Henry Moore in those days was “the man”, people would gather round and start conversations and Eric would say “Henry…er Henry?” Henry Moore was also educated as a classical sculptor.” [29]

Eric admired and enjoyed Moore’s work although he said “his language is somewhat removed from my own.[30] In April 1967, Eric’s “The Musician” was exhibited with Henry Moore’s “Reclining Figure” (LH402) and the work of 58 other sculptors at the International Sculpture Exhibition in Pittencrieff Park, Dunfermline. Locals remember this exhibition fondly. It was estimated to have attracted 30-50,000 visitors; perhaps it is time for another.

Leonard Rosoman was an ECA tutor in the 1950s and in conversation with Chiara (c.2003) remembered that some of their teaching colleagues thought Eric was “too kind and too gentle to his students”. He was a “very quiet, strong man… he didn’t have to raise his voice, he had enormous influence by just quietly talking to people.” Leonard Rosoman also recalled the kind hospitality and parties at (the) Meadow Place (studio) when he first arrived in Edinburgh, important to him after his time as a war artist and the suicide of their mutual friend Bernard Meninsky which, he said, had hit him hard.

Another student, Zigi Sapietis, the Midlothian-based sculptor, recalled to Chiara in 2003: “’Simplicity is the greatest thing and most difficult to achieve’ he told us, while his wooden spatula spread clay over our life-sized statues… Mr Schilsky used to stay on his toes and swing gently backwards and forwards while smiling and surveying our class with the naked female in the middle of it, before starting his tuition. We students quickly wiped out all the composition lines marked in the clay of our statues by the previous tutor. Mr Schilsky wanted to see a clean, pure surface of the clay modelling, the bare simplicity.”

Carol Carnevale was Eric’s model at ECA from the late 1950s until Eric retired in 1968 and was the subject of his last life figure which he never completed. Eric destroyed it just before he died. She modelled for classes and in his college studio after hours, including Saturdays and Sunday mornings, while he worked slowly and painstakingly trying to achieve a perfection which constantly eluded him. Eric would draw his models from every angle in preparation, he measured from the life with callipers and worked with a small amount of plaster mixed to a paste in a tennis ball, applying it to his figure with a spatula. It was very, very slow. Classical music played at all times while he worked, particularly Mozart or Brahms, sometimes Desert Island Discs but never jazz, which Carol Carnevale would have preferred.

Chiara met with her and recorded their conversation in 2002:

“Your father was very private, I mean he hardly spoke, you know… he would speak about Maillol… I spoke to my sister-in-law… and I said ‘I always wondered why Mr Schilsky was fascinated by me all the time’, and she says ‘because your figure was like what Maillol would sculpt and you were a typical Maillol subject’… he thought Maillol was wonderful... and there's a statue down in the Modern Art Gallery and when I saw it, yes it could have been me… I went with a friend of mine and she was at Glasgow Art College… and I says… ‘God, I could have modelled for that’, because it was so typical.

“He was very exacting, and very perfectionist… I'm not an artist nor a sculptor but to me he would work on a certain part, an arm, or a shoulder and he would do this for weeks on end, you know, just the one bit, and then suddenly he would move completely, and he would put it all on the front and take it off the back and actually the statue was walking forward if you know what I mean… his work was beautiful, I'm not one to judge, you know but he was never satisfied I felt with his work… he used to saw the hands off a lot, my hands, and then he would put another armature in and then start all over again and then he also sawed the arms off!”

“He wouldn't show this to anybody, if anybody came into the room, if they knocked on the door when I was modelling for him he would cover it up, he wouldn't let anybody see it."

“I think he was proud of his works that he had round the studio, but he wasn't too happy with the work that he was doing, that's my impression… the figure that he was making of me, I felt that he was never satisfied with it, I don't know why… but the rest of his work was round the room, and he was very proud… of the one of the girl, the golden head (“Patricia”)…and the man with the hands (“The Musician”) and even I thought that was very expressive, 'cause I used to say to him: "How did you get his expression?" (and Eric replied) "Because he talked all the time!”

William Brotherston spoke with me in 2020 and recalled his figure “Carol”:

“His practice was to model directly from the figure in plaster onto a metal armature, and he seemed to work very much from the front of the figure, adding plaster at the front and taking off at the back, so that it in effect “moved forward.” Consequently, he had to have the original metal armature cut out and a new one somehow put in from the front. This work was done by Dave Cohen.”[31]

Chris Hall, then a sculpture student, also helped in Eric’s studio. He spoke with Chiara in 2002 and 2004:

“Eric had a very strong sense of what for him was right and he was trying to achieve it… over and over again. He was trying to reach out for this almost chimerical thing that he thought he could discover… I think he adored his models… their beauty… he was wedded to an ideal which was in a way, his undoing… Big in feeling; that was a very important concept for him… it’s to do with tremendous observation and… the selective process, so that you don’t look at the small forms... and try to see it as a whole. He had this thing about “the order of approach;” that was one of his great sayings, from the large forms, the large shapes, and then eventually you could look at some of the smaller forms.”

He remembers Eric working on “Carol”: “what's in a way tragi-comic is that the figure itself was moving very slowly away: forward… what would have been very handy, would have been if someone came along and said "Stop there, that's perfect”. But no one ever saw him work. He was intensely private… he had to isolate himself from the very thing that would have saved him… that would have saved that work.”[32]

Eric Schilsky with an armature (Carol) at the Edinburgh College of Art. Photograph probably taken by Dave Cohen, c.1955. Private collection.

Simon Manby, Eric’s student in the early 1960s, wrote to me in 2020:

"Was it ultimately a failing and a weakness of his teaching that after five or six years of dedicated study, many of us left the Edinburgh College of Art overburdened with a sense of humility and too acutely aware of the limits of our own artistic merit? Perhaps those feelings were part of the zeitgeist, but I think Eric Schilsky instilled in many of his students, the ambition to go forward, to not give up, to make learning a life-time pleasure and its reward.”

“I'm still making sculpture and Eric Schilsky even today sometimes hovers at my shoulder!”

In c.2004, Chiara asked the sculptor, Michael Snowden, Eric’s teaching colleague at ECA, why he is so little known. Michael replied:

“If he had stayed in London through the Royal Academy, etc, he would have got commissions. He was offered a post at the Royal College by Robin Darwin in about 1946 but he felt he could work better here (in Edinburgh). He never joined the rat race or spent his energies on publicity. All his energies went into teaching and what was left after that into his own work, so it was sacrificed for his devotion to his job of Head of the School of Sculpture. He would get to the college at 8am to work before the students arrived and stay till the College closed very often, working from 4pm onwards, then all day Saturday and half Sunday. But his works were, though simple, meticulous, and they took a long time.”

In response to the same question; Kevan Coultan replied:

“To have known the man would in large part answer that question. Perhaps it was due to his great humility, in worldly terms he was unambiguous and he was unmoved by changes in fashion. “Quality, not quantity is what matters,” he would say.”

Ann Henderson, the sculptor and Eric’s ECA colleague, wrote in his RSA obituary:

“He was happy and contented with life in Edinburgh - indeed, he loved the city. On many occasions he was heard to say to students who yearned for the great art centres - "We are fortunate to live 400 miles from London - here we have peace to work, and yet the possibility of visiting any centre to look at works or exhibitions within a few hours of travel."[33]

In December 2024, 50 years after Eric’s death, his bust of Jean Fletcher Watson, who endowed the City Art Centre’s collection, was brought out of storage and is now in pride of place just inside the entrance door on Market Street. This was the first work purchased by her Bequest Fund in 1961 and was exhibited and reviewed as a “stand out” exhibit at the RA in 1964. [34] It is also a pleasure to see that Eric’s bust of Gillies is central to a display in the current “William Gillies, Modernism and Nation Tour 2024-2025”. The two artists were close friends and used to paint together. Eric’s bust can be seen at William Gillies’ home in the 1970s film (by Ogam films) being shown at the exhibition: “Still Life with Honesty”.[35]

Eric Schilsky. Sir William G Gilles. 1956. Plaster. 28 x 20 x 23 cm. Private collection (also in the collection of the Royal Scottish Academy [William G Gillies Bequest])

In the film, William Gillies remembers an anecdote:

“Eric Schilsky was asked by the income tax man why he persisted in sculpting, when obviously, he got no financial gain out of it, rather a loss. He told the man it was an obsession or a disease he suffered from, but he would rather not be cured of it.”[36]

Eric died suddenly in March 1974 just as, according to Victorine, he had finally adapted to his retirement and was sculpting again in their studio. She was the driving force behind the Scottish Arts Council touring exhibition of 1976 and subsequent exhibitions in 1977, 1980 and 1998, arranging new castings and curating Eric’s archive. Chiara continued this work after her mother died in 2000 and I am most grateful to her for giving me access to her research and family papers.

Anne Emerson

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS:

With many thanks to Chiara Schilska, Jay Storic, Nick Haynes, James Holloway, Campbell Armour, Lady Diana Philipson, Simon Manby, William Brotherston, Christelle Soëne, Fiona Pearson, Sally Weir, Michael Snowden, Zoe Emerson and Richard Emerson.

All photography (except images 7 and 10) by Nick Haynes. All images and artworks copyright of Chiara Schilska.

[1] Certificats, Diplômes et Prix de Concours, L’Ecole des Beaux-Arts de la Ville de Geneve, le 26 Juin 1914, pp. 8-12

[2] Kevan Coultan, Introduction to Eric Schilsky, Scottish Arts Council Exhibition Catalogue, 1976

[3] The Observer, 6 May 1923

[4] Victorine Foot’s biographical notes on Eric Schilsky, prepared c.1990

[5] Kevan Coultan, op.cit.

[6] The Studio, 1926

[7] “Practically True” by Ernest Thesiger, (Heinemann, 1927), p.13

[8] Transcript of Chiara Schilska interview with Andrew Brown, c.2000, artist’s archive

[9] A bust of Gabrielle Soëne (catalogued as Gabrielle de Soane) in the collection of the National Galleries o Scotland, GMA 1525, purchased 1976

[10] The American Magazine of Art Vol 15, No 9, September 1924

[11] Interview with Blake Morrison in The Independent, 13 August 1994

[12] The Studio, 15 February 1926, p.104

[13] The Observer, 3 May 1925

[14] Letter from Eric Schilsky to Victorine Foot November 1944, artist’s archive

[15] “Bettina”, an oil painting of Bettina in profile adjusting her hat, and “Lady in Mask”, which featured on the cover of Drawing and Design, Vol 4 New Series V, October 1924 and “caused a stir”; Gluck her biography Diana Souhami, 1988, p.53

[16] Aldous Huxley “Beyond the Mexique Bay” (Academy Chicago Pub, 1934)

[17] Interview Chiara Schilska with René Schilsky, 13 June 1998, artist’s archive

[18] Daily News (London), 17 January 1929

[19] Concealment and Deception: The Art of the Camoufleurs of Leamington Spa, 1939-1945 Exhibition Catalogue 22 July-16 October 2016, p.13, p.73

[20] Coventry Evening Telegraph, 20 February 1943, “Leamington Man’s Tragic Discovery”

[21] Testimonial by Bernard Meninsky, Oxford, 13 April 1945, artist’s archive

[22] Minutes of the Board of Governors meetings, Edinburgh College of Art 1945-1974

[23] Letter from Eric Schilsky to Victorine Foot, 3 November 1945, artist’s archive.

[24] Interview Chiara Schilska with Andrew Brown, 2003, transcription in artist’s archive.

[25] The model for “Tamar” was Antonia Young, another daughter of Herbert Marks, then a student in Edinburgh

[26] Unattributed press cutting in artist’s archive, “Best Sculpture Show for a Number of Years”, by Felix M O McCullough

[27] Illustration of Patricia: http://ericschilsky.co.uk/?portfolio=patricia

[28] “Dave Cohen, ceramic artist and teacher” Obituary, The Scotsman, 11 July 2018

[29] Conversation between Dave Cohen, Andrew Brown and Chiara Schilska, 1998

[30] Letter from Eric Schilsky to Victorine Foot, 26 April 1944, artist’s archive

[31] Correspondence between William Brotherston and Anne Emerson, 2020

[32] Interview Chris Hall and Chiara Schilska, June 2004, artist’s archive

[33] https://www.royalscottishacademy.org/artists/544-eric-schilsky-rsa/overview/

[34] Daily Telegraph, 1 May 1964, “Realistic Approach by the Royal Academy”

[35] “Still Life with Honesty”, National Library of Scotland Moving Image Archive 2686 https://movingimage.nls.uk/film/2686

[36] Ibid