Faye Eleanor Woods: Surrealism in the Everyday

Faye Eleanor Woods. Foot Chess. Raw pigment and acrylic on canvas. 25 x 20cm.

Whilst I was wondering what to write my next art-scot article on, my eyes wandered around to my own walls and landed on a small painting by Faye Eleanor Woods that I bought a few years ago. A fun work showing a foot dextrously lifting a chess piece to pop onto the board. Swathes of pink are offset with various tones of green. A fallen pawn lays to the side, perhaps the previous failed attempt to pick up a piece. At the bottom is an intruder, an opponent, or merely a voyeur to the spectacle.

Faye Eleanor Woods is a painter that I can’t quite remember discovering, but it feels like I’ve always known about her, and I’m glad for it! Her paintings are whimsical, rich, colourful and indulgent; mostly with a central, female figure that dances across various settings like Glasgow suburbs or pub interiors. What looks initially unusual or surreal becomes more and more realistic and tangible as you fall deeper into her all-encompassing colour schemes of blues, greens and reds. Woods grew up in the west of Scotland before moving to Aberdeen and Glasgow. Now living in Manchester, she still daydreams of her homeland. As a Scottish artist now living in England, Woods’ work does feel like a dream of Scotland with nods to Glasgow, Alasdair Gray, and the cold wet weather.

I emailed Faye some questions and she gave me a great insight into her work, use of media and inspiration.

Woods in her studio. Photograph by Louis Christodoulou

I first asked Faye about her early inspirations as an artist, and she came back with Egon Schiele, Gustav Klimt (also a duo I was a huge fan of during my Art A-levels), and Alphonse Mucha. Beginning with an Illustration course, Woods soon switched to Contemporary Art Practice and felt she could work more freely from then on. Although she says her work is very different now, as well as her inspirations, I can still see a nod to the abundance of colour and texture that Schiele and Klimt achieved. From Contemporary Art Practice, Woods then studied at Gray’s School of Art, Aberdeen, leaving with a BA in Fine Art Painting in 2021.

Her current inspirations still feature well-known artists, or what she calls “the big dogs”, Lucian Freud and Matisse. She also looks to the contemporary painting scene and named Italian artist Guglielmo Castelli as another solid inspiration. I can especially see the parallels with Woods’ own work here. Deep, rich colour schemes and flowing, floating figures that stretch over the canvas.

Guglielmo Castelli, Permanenza Statica. Mixed media on canvas. 50 x 40cm. 2020.

I next asked Faye about her origins as a painter and how she approaches a work. Shockingly, at the age of 16, she was told by an art tutor that she’d never be a painter because “she didn’t get it”, whatever that means! I was happy to hear that she “still bitterly bemoans that woman”. The joy in painting is there can be no rules. The possibility is there to cast aside what has gone before and be free in the gesture of putting paint onto a surface. I’d say Faye Eleanor Woods has certainly “got it”. Paint is also forgiving. Whilst it is still wet, you can wipe away brushstrokes and pigment. This is another element Woods enjoys as she delights in making mistakes:

“I like paint so much because I love to make lots of mistakes, I really relish it. A canvas can really take a lot of mismarks and wrong layers in a way no other medium really can.”

Woods in her studio. Photograph by Louis Christodoulou

Woods also uses an interesting mix of different media on each work. What was originally borne out of necessity and cost is now an integral part of her process:

“At uni I started with oil paint like everyone else. Oil on MDF and then oil on primed canvas. But it was my second year when I first tried distemper (raw pigment and rabbit skin glue) and I've been hooked ever since. I began mixing mediums out of necessity. I had limited funds and limited resources and I just used whatever colour was right regardless of the type. This means I’ll have areas that are pigment, ink, acrylic, oil, varnish, pastel etc all on top of each other. Whatever feels right.”

Her impetus on the right colour really shines through. A lot of Woods’ works use what I would call an all-encompassing colour scheme, whether this be blue, green, or red. Multiple hues of each master-colour seep into every pore of the canvas. The different qualities of each medium, whether acrylic, oil, ink, then give each colour a real depth. Woods’ ability to get all the possible hues of one colour she desires is a real masterclass.

To start a painting, she begins in the sketchbook. These fast drawings are a great precursor to the finished canvas. She notes that being on a train also lends itself well to these fast, what she called cartoonish, lines;

“I size with rabbit skin glue or acrylic primer and then start with thinned out layers of distemper. I use a spray bottle of water so the canvas is always slippery and this allows the paint to be layered in super thin coats. I will then add acrylics and oils in various areas where I feel it needs it. I am a very quick painter! I was once told I attack paintings like a bulldog! The painting itself is explosive but I take a lot of time to just stare and do nothing too. Say a work takes three weeks to make - It may be only four days of active painting and a lot of trying to catch it out of the corner of my eye to figure out what it needs.”

I love this image of her attacking a painting like a bulldog! This energy and movement in her process really shines through into her work.

Faye Eleanor Woods. It Starts and Ends with Anniesland. Raw pigment, acrylic ink and oil on canvas. 168 x 152cm.

It Starts and Ends with Anniesland is a great example of Woods’ ability with colour and medium. A wild and woolly weather covers a scene of the Glasgow suburb. The central figure glides over the streets, which threaten to become a river beneath her feet. In the background are the Temple Gasometers, originally built in 1893 to store coal-produced gas, which now stand derelict and haunt the skyline. At the very top of the work, fiery oranges threaten the brink of apocalypse; but fear not: the rainy Scottish weather dampens any hellfires. The inky royal blues at the bottom move up into solid patches of azure in a wash of lush blues. This work certainly feels like a dream of Glasgow. A known skyline is disrupted with sprawling vines and limbs, and the blue filter makes everything looks unlike itself but also recognisable in equal measure.

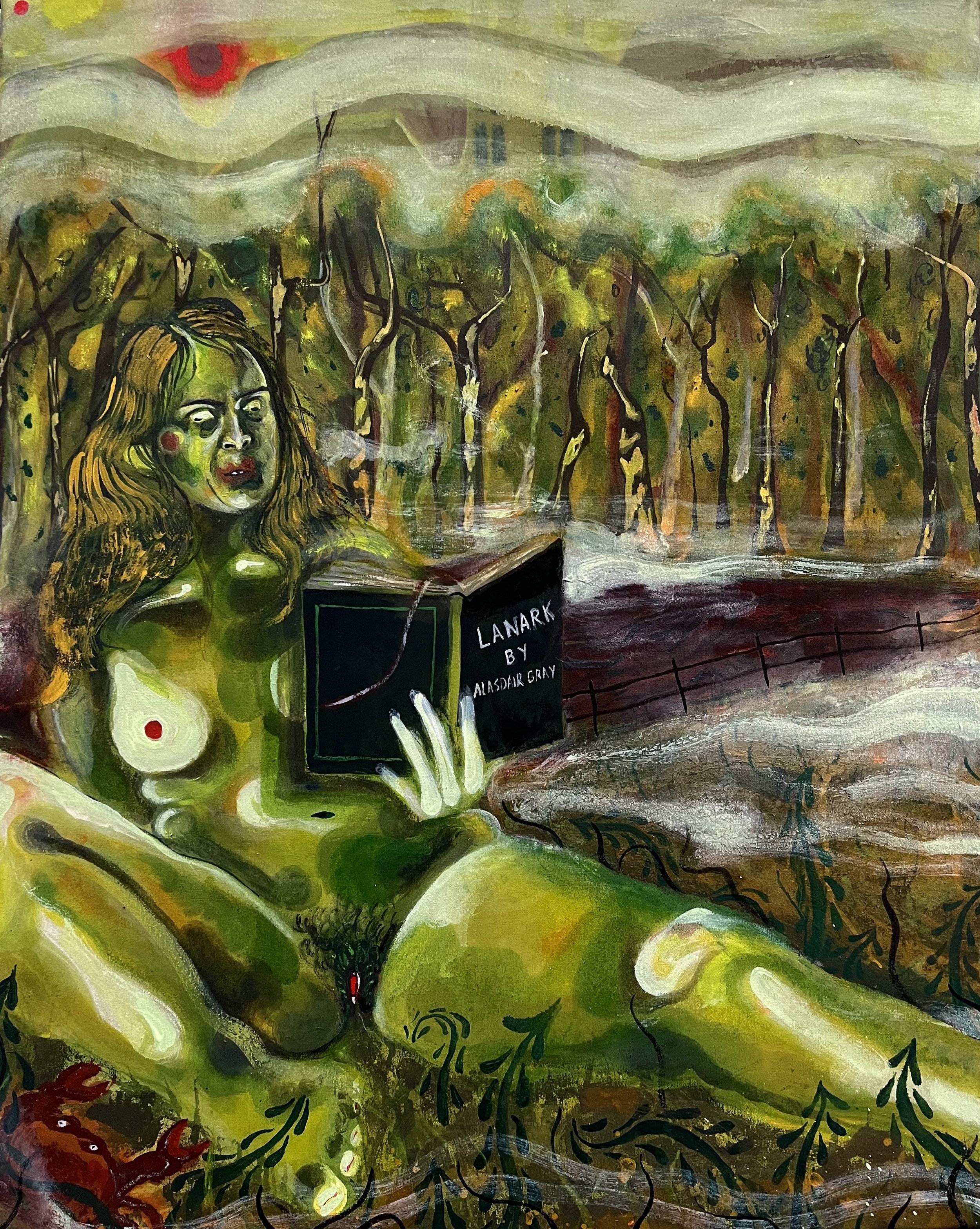

Scotland creeps into Woods’ work regularly, despite her being far from home. In one work titled And When I Close My Eyes, I'm Not Here, I'm THERE, Woods goes to Alasdair Gray for inspiration.

Faye Eleanor Woods. And When I Close My Eyes, I'm Not Here, I'm THERE. Mixed media on canvas. 76 x 60cm

The central figure lounges reading Lanark (1981), Gray’s most famous work, and noted as being one of the cornerstones of modern Scottish literature. I asked Woods about her thoughts on Gray:

“I like everything about him really. His paintings, his writing - the stories about his character. He was a rare individual. I think people like him come about every so often, they are just exceptional and we must take it all in. Devour all they have to offer. He writes about Glasgow in a way that seems so easy and mundane but so magical. It’s realistic in its surrealism.”

This idea of mundane as extraordinary, or surreal as realistic, is definitely something we see in Woods own work. If Gray writes like this about Glasgow, then Woods paints like it.

There is a surreal element to Woods’ paintings; the real feels unreal, the recognisable becomes skewed. This everyday mysticism is something Woods does extremely well. She notes that she often looks towards folklore for this uncanny quality to her works. These nods to symbolism and Woods’ ability to put her own spin on things are clear in the painting Hungover at Mass. A striking, smoky, pale work done almost entirely in whites, creams and pinks is a unique way to utilise traditional religious imagery.

Faye Eleanor Woods. Hungover at Mass. Raw pigment, acrylic ink and oil on canvas. 183 x 106cm.

The central, Christ-like figure is being supported and brought down (or being escorted out?) by the surrounding figures, faces and hands. Whether they are helping or hindering is up to you. The title might suggest that the main figure’s drunkenness is the cause of her expulsion, but the framing of the central figure is heavily reminiscent of paintings showing The Descent from the Cross. See the below example by Rubens, dated 1612-14. Christ’s body is uncomfortably slumped and heavy; imperfect, unlike so many other depictions of this scene. The people around the body are encumbered by the weight of his body. In Woods’ ‘version’ we see a similar treatment of the figure; drooping and uncontrolled, this time by wine!

Peter Paul Rubens. The Descent from the Cross. Oil on panel. 420.5 × 320cm. 1612-14. Cathedral of Our Lady, Antwerp.

To the bottom left of the scene, a chalice is knocked over and spills. Perhaps our hungover, still-slight-squiffy heroine reached for the communion wine during the service. The subtle pale pink of the floorboard appears almost as if the blood-red wine has soaked down into the grain of the wood. If you follow the red around the scene, you realise it is now everywhere. From raw knees to the inside of the upper thigh, to the upper body and finally dripping from the mouth.

These red knees and mouths are a common feature of how Woods paints her central character, who is nude in almost every scene. This nudeness is not sexual. This is something Woods is adamant that viewers understand. It should go without saying, female nudity does not equal sex, and her work is only sexual when she says it is.

With this firmly in mind, the way Woods paints her central heroine profoundly captures womanhood. With the knobbly knees, grotesque facial expressions and clumsy limbs, the character is allowed to be untethered to or weighed down by the male gaze, and therefore can indulge in peace! I asked Woods in which ways this figure is her, or an ideal. Her answer is a great one:

“She is me but she isn't me… I’ve made it a bit of a caricature of myself. They always have my messy dark hair or my very red cheeks or flat arse… I think I'm just a big minger really. It all boils down to the fact that I take a lot of pleasure in being kind of a hedonist. I care a lot about what it really means to be a woman. The reality of it is that we are these wonderfully full creatures. To be a happy woman is to indulge in everything the world has to offer us. Really go for it and consume all the good and the ick.”

An entertaining way in which this idea of consuming the good and the ick manifests in her work is through the returning character of the black stuff: Guinness. Whether as a harp arm tattoo, on a pub bathroom mirror, or in its old-fashioned form as a perfect pint. Guinness does have a certain mystical quality, and arguably some of the best marketing ever. Name another beer where the punters can police their own pint? Often in pub scenes, amongst swathes of wispy smoke, Guinness takes on a mystical role in Woods’ world.

Guinness has a long history of attempting to paint itself as healthy; that it is full of iron, and even good for pregnant women! Obviously this is all rubbish, but these are interesting links to womanhood. Most recently, there’s talk of Guinness themselves attempting to market themselves towards women directly and away from merely a drink blokes have after the rugby. More widely with beer, there’s an element of it being supposedly un-feminine, or unsophisiticated, which adds another interesting lens to Woods’ tackling of the pub setting, and women’s (rightful) place in it.

Faye Eleanor Woods. Oh No, It’s Her! Raw pigment, acrylic ink and oil on canvas. 127 x 107cm.

In my short-lived days as a bartender in a Leith old man pub, I must say, pouring a perfect pint of Guinness was a semi-profound joy. In this way I get it. I’m personally not a fan of consuming it, but I appreciate its ubiquitous place in the landscape of UK pub culture. I asked Faye if she could convince me about Guinness’ place in the world as a stout hater and she says:

“Stout is trash. I don’t want my beer to taste like coffee or chocolate. Guinness is a secret third thing. Blood and lager and cream. A bitter gravy.”

I’m convinced! If something can gain such mythical and cultural momentum, then its existence legitimises itself. In this sense, I like to think of the Guinness in Woods’ paintings, as akin to the chalice of wine featured in Hungover at Mass. A holy beverage to be consumed in the ritualistic event of going to the pub.

The monolith that is the British pub is also a recurrence for Woods. I asked her why this was and she told me that she was around pubs from a young age and there is a comforting, familiar element to them. I also asked whether there is such a thing as a perfect pub, and this was something she has mused over before!

“Pubs should have fires. They should have stone or wooden floors. They should only be painted red or green inside. They should have booths and round tables and stools. There should be big mirrors and historical photos and strange objects on shelves. They should serve chips. The music should be so low I can barely hear it, but it should be there.”

I must say, I totally agree. After I finish this article, I will promptly be taking myself off to my closest example of Woods’ perfect pub; the Malt n’ Hops in Leith. Not a comprehensive match for match, but fire, red, mirrors, music and miscellaneous knick-knacks are all a tick.

Ultimately, Woods’ work is a profound, but also everyday depiction of a woman navigating through urban life. In her humorous, whimsical, dreamlike scenes, women are allowed to be menaces, to be drunk, loud, clumsy and powerful. We belong in all settings, even dreamed ones. The depictions of Scotland are also both imaginary and real in equal measure; using recognisable skylines, characters, and references, but placing them in a wonderland of hues and texture. Woods is truly depicting the surreal in the everyday.

Rosie Shackleton

Acknowledgements

With thanks to Faye Eleanor Woods. Images courtesy of the artist. Photographs of Woods in her studio courtesy of Louis Christodoulou.