Ian Fleming: Graphics & Peacocks

Ian Fleming talks about Graphic Works and Peacock Printmakers

Introduced by Malcolm McCoig

Malcolm McCoig talked to Ian Fleming in 1986 about creativity and graphic work. The cassette recording has been untouched since then, and we're excited to publish it for the first time.

To complement the transcription, we thought it would be interesting to reprint the wonderful document that Peacock Printmakers produced in 1983 to accompany the exhibition, Ian Fleming: Graphic Works (Note 1). This is not an easily accessible publication. The core element is an essay by Ian Fleming edited from another transcribed interview (Note 2).

Malcolm wrote the original foreword to that publication, and here he brings a new perspective by offering a fresh introduction and a set of notes.

Introduction

I wrote the introduction to the Ian Fleming:Graphic Work publication nearly 40 years ago. So, what now is there to be said? Obviously I’m 40 years older and am now the age Ian was then, so I have a very clear perspective of what it is like to be that age and now have an even greater appreciation of what he was doing then.

In rereading the marvellous text after all these years, I was most impressed with the in-depth portrait of the man, his common sense, reality, intelligence and his eagerness to just get on with it, or as he would say, “just belting it out”.

The execution of his last two major print series, “Creation” and “Comment” was a mammoth task, not just physically, but technically and emotionally. To produce such a variety of images and compositions is very demanding, but to do it on over 30 copper plates, all in reverse, and then to print the damn things is, believe me, hard work at any age. Pay attention to what he says about them and all the other gems scattered throughout the text.

The taped interview with me, well, a wee chat really, was I think when Peacock Printmakers had a big Talbot Rice show, “Recent Work”, in 1986 and I was hoping to get a bit more information out of him for his contribution to the catalogue – a bit cheeky of me, I suppose, but at least we now have the great man speaking a lot of good, factual, enthusiastic stuff.

The photo from that catalogue of Peacock staff and committee, sitting on a big pile of lithographic stones, is a delight to see again and takes me right back to these marvellous, inventive and productive times with Ian, right in the centre, where he quite rightly should be.

Malcolm McCoig, November 2022

Photo - Peacock Board and Staff, 1986 (Note 3)

Ian Fleming: Graphic Work - The 1983 Exhibition Brochure

A Peacock Printmakers Exhibition with the Support of the Scottish Arts Council.

My first encounter with Ian Fleming was in the tense and formal atmosphere of a job interview. At the time, I wondered who this single, sympathetic member of an otherwise academic panel was? Ian Fleming was to become my new boss.

It was in his role as Head of Gray’s School of Art that I first got to know a little about him. He had the ability to quietly defuse situations and find simple and sane solutions while dealing with temperamental staff and difficult students. In those early years, his advice and encouragement to me as a new teacher was invaluable.

Soon after retiring as Head of School, Peacock Printmakers was being formed, and Ian Fleming was asked to be chairman of this new group – a post he has held without a break since 1974. A great deal of Peacock’s success lies in the fact that he has been a tremendously stabilising influence in a committee, which in its earlier youthfulness and innocence, could occasionally lose sight of correct procedure and practicability. This is not to suggest a cramping of ideas, rather the opposite, where the exciting new thoughts put forward were helped into reality through his chairmanship, experience, correct spelling and personal contacts.

The workshop played its part too, by providing him with excellent printing facilities. But this is only half the story, the energy and ideas still had to come from him; and they came pouring out!

As well as surviving as an ex-Glasgow policeman, he has been gravely ill several times, but refuses to dwell on the latter, although the former offers a wealth of fantastic stories. He simply wants to get on with his art, and hopes that the Dons and Clyde F.C. might always do better. His wife, Cath, is such an integral part of ‘The Flemings’ that her role has been vital to his successes.

I have often helped him print, and he is a delight to work with, having neither tantrums nor a fear of experimentation. It has been my pleasure to have spent so many hours in his company.

This exhibition is not only about one man’s tremendous achievement, it is a landmark in Scottish printmaking.

Malcolm McCoig

January 1983

Brochure Cover

Ian Fleming’s Exhibition Brochure Essay

the dirtiest place I’d ever seen

I had never any doubt, when I was at school in Glasgow that art was the thing I was going to pursue. My father was a painter and decorator in Byres Road and he used to do little watercolours. He used to copy Raphael Tuck postcards. I admired my father very much. He was a nice wee man. ‘The British Decorator’, a trade magazine, came into the house with all sorts of colour patterns and wallpapers in it. When I was a boy I went round with my father in the evenings when he was doing estimates for work. This was all round Hillhead and along as far as Highburgh Road and Hyndland Road and up towards Kelvinside, a very posh part of Glasgow. He usually took me along to hold the tape while he measured the room. I was greatly intrigued by these huge pictures with enormous gold frames hanging on the wall. You couldn’t see the wallpaper they were so close, and I couldn’t understand why they wanted to re-decorate. Some of the wallpapers were very expensive – brocaded velvets. I had a dressing gown made by my mother which came off a West End wall. Of course we were quite near the Kelvingrove Art Gallery and my chums and I went in there quite a lot to see the ships mostly. We were always chased away as being too noisy for such a mausoleum of a place.

These things may have given me a sense of direction towards the visual arts. But very early on when I went to Primary school I discovered very quickly that I could draw better than anybody else. We used to draw biscuits and envelopes and jelly jars. We were in these funny classrooms with tiered desks and way down at the bottom was an envelope stuck on a board on a table and you were supposed to draw this although you could hardly see it, or it may be a biscuit, or a banana. Later on, as you progressed, you got one of those lovely stoneware jelly jars to draw. Not to shade but just to draw the outline. I discovered that I could make a better image than most of the class – that’s a very important discovery for a child. It gives you confidence – this minor success: that you can kick a ball better than somebody else or you can draw better. I was always interested in drawing thereafter. Even at Hyndland School, I was always first or shared-first in the Art Class. But at school I didn’t have any idea where the Glasgow School of Art was. I discovered it was the big barracks-like structure behind what was Hengler’s Circus, which was a marvellous place for Glasgow children. They all knew Doodles the Clown and the Great Waterfall that took place at the circus – an annual pilgrimage for all.

When I eventually went to the Art School, I thought it was the dirtiest place I’d ever seen. They used to deliver the coke and coal at the front door. The lecture theatre – in company with everything else that MacIntosh did, was marvellous to look at but to sit in the place was absolutely appalling. The chairs too look marvellous, but they were not very good to sit on.

In those days everybody went into the life-class and the male models were in the altogether. I will always remember the first day we went in there, we were absolutely shocked when we saw the man standing there in the nude. In the first year we were not allowed to go into the first year class for females because the woman was in the nude. In the second year you were introduced to the female. The studio had a thick partition wall which could be taken down for dances, and the first year students had bored holes through to the second year rooms next door, so by the time you arrived in the second year you knew what to expect.

And if you go to the Glasgow School of Art you’ll find that all the classical figures have a wee nail protruding just above the private parts because old Jimmy Dunlop, who was the anatomy man, made lead leaves and nailed them on. This was the sort of puritanical atmosphere. To this day there are still one or two casts with the nails sticking out. It was a strange atmosphere – very restrictive. My mother was quite shocked. She didn’t know that I was drawing nude females until she came to see my Diploma show. I saw her face go very rigid. She said ‘I didn’t know you drew naked women’.

There was a very strong dramatic society in the art school at the time – under Dorothy Carleton-Smyth. She used to bring famous actors and actresses up to the School and they enrolled students such as myself as extras. I remember being on the stage in the famous Henry VIII play with Sybil Thorndike and Lewis Casson and Lyle Sweet as Cardinal Wolsey. We had walk-on parts. We were part of the crowd in the famous Madonna with Lady Diana Cooper and we did walk-ons with the Esme Percy Group. That’s where I became interested in George Bernard Shaw, and the theatre.

I then tried woodcut

The first prints I did were the coloured woodcuts. When I arrived at the Glasgow School of Art in the first year, Drawing and Painting was the pre-eminent Department, with the Life Class the supreme test of ability. Craft was only done two days a week and you had to come back in the evening to do it. You had to select two crafts. I went bouncing around and had a look at etching – which was called ‘Craft’. I then tried woodcut. I had done some small lino-cuts at school but I hadn’t done any woodcuts or etchings. I didn’t even know what it was. So eventually I decided on lithography and woodcut at the night class. It was rather an interesting and very genteel lady called Chika McNab who took the coloured woodcut class. She was the sister of Ian McNab who started the Grosvenor School of Art in London and later became the McNab of the McNab and one of my contemporaries was Winifred McKenzie – one of the two McKenzie sisters – brilliant wood-engravers.

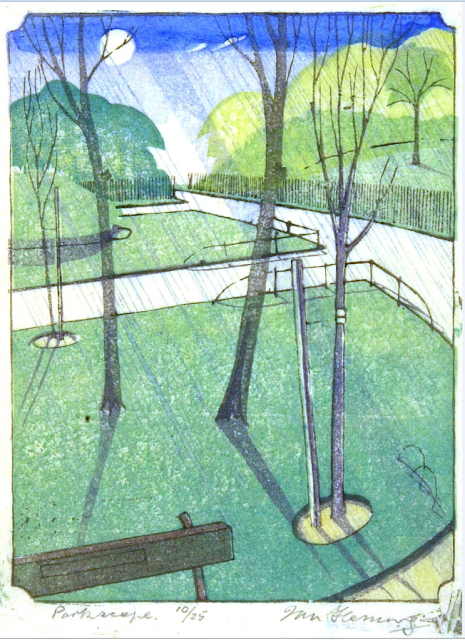

Parkscape

It was the old Japanese method that was actually used. There is no printing ink on these woodcuts. We bought powder colour and made up our own rice paste, that was the medium. With the brush and some water, almost like watercolour, we brushed it on to the block. That’s why they are so fragile looking by way of colour and there is a lot of the ground actually shining through.

The first year I did the black and white one of The Glasgow University. We did two or three in black and white to get used to the tools and then went on to the coloured prints. You can well imagine that there was a lot of difficulties with keying, because after a while the paper started to dry and shrink, and if you had water-based pigment on the block, that increased the dampness and it became ‘a bit of a bind’ to key-in the different blocks. We always had very, very serious problems with keying, using water-based pigment.

Most of the papers were Japanese rice paper. The Japanese used cherry wood for the blocks, we just had to use plane tree so you couldn’t get the same fineness in the block as you would with cherry tree which is almost like box tree. You will see in the very best Japanese prints – those of Hokusai and Hiroshige, the hair is almost a wood engraving rather than a woodcut and this is because of the nature of the wood they used. But working with cherry tree is very involved, like box it had to be finely joined together and was extremely expensive, whereas you could get a great big block of plane tree which was fine and dandy and did the job. Some of the drawing that you see there – it even amazes me now that you could actually cut that, it’s such a fine line. I must have had a steadier hand than I do now.

I can’t remember very much about my lithographic experiences. I did several really atrocious things. I remember using a photograph of Robin Hood’s Bay and making a coloured lithograph. There must have been quite a few, but I later had a fire in my studio and I lost an awful lot of drawings and plates and paintings and I rather suspect that these awful lithos were also lost in the fire. The prints that have survived had been put into a portfolio and sent to my wife’s mother’s house. The use of photograph in the Fine Art area was regarded as beyond the pale – a sign of grave weakness. How attitudes change!

Glasgow Tenement Window

Of the work I was doing then, two of the woodcuts were the first student work ever bought by the Glasgow Art Gallery – The Glasgow Tenement Window and the one with the Aspidistra and they have been in the Glasgow Art Gallery print room since they were purchased from the student show.

I got my Diploma in 1928 and did a Post Dip. in 1929. My diploma was in Drawing and Painting and I got my Post Dip. Scholarship in painting largely on my life-drawing and draughtsmanship. Charlie Murray, a native Aberdonian, had come back from the British School in Rome. He was an alcoholic. He was looking at my Diploma drawings and he said ‘You know you shouldn’t be painting, you should be engraving’, and he handed me a wee plate and that’s the Portrait of a Woman – my first engraving. There was a whole lot of flaws in it, but I was really trying to find out what was what. I got it on the Friday and he handed me a tool, a burin. I went away home and started belting it out and arrived back on the Monday and handed it to Charlie, he did a wee bit of scraping, taking the burr off. I didn’t know you’d to take the burr off, or even that the burr was in an engraved line. As a result, the first two or three prints are rather like drypoint because of it.

I became rather more than interested, absolutely obsessed by engraving. All this concentration that I had always had on line began to take meaning. Instead of a pencil point, I now had this firm, very, very disciplined way of trying to achieve a form.

The reason I spent so much time with Charlie Murray in my Post Dip. was because of his drinking. He was drinking meths and when he came in to the class in the morning I would have to put him to bed in his studio, next door to the class, and take his class for him. I got the paintings and etchings I have of his because when he used to ask me for money, for a drink, I would give him a quid, which I could ill afford at the time, and he would sometimes hand over either a painting or a print saying ‘You hold on to that and when I give you the pound back you can return it’. Because he handed me that wee plate to start with and pointed me in a certain direction the result was that throughout my Post Dip., I did nothing but engraving. This fulfilled the idea that in your Post Dip. year you did exactly as you would do if you were an artist in your own studio. I always insisted that’s what should happen at Gray’s. When I was a student I used to set up a canvas at home on the back of a chair with a friend as model but you can’t do that if you’re a sculptor. That’s why the Post Dip. year is so important and also why workshops like Peacock are so vital. A student leaves art college with a lot of expertise, but he hasn’t the equipment or studio to further that expertise. The other things is the stimulus. The influence of students, one on another, is a very important factor in an art college and one which isn’t often recognised. One of the great things about art college is that you bring people at the same stage together with the same interest – you give them the tools. The significant point is not that you give them expertise but that you give them a sympathetic environment in which to grow and develop. So that they will have the stimulus to go on. If you have two or three good students the whole standard of that class will go up.

people don’t do big plates like that

I didn’t accept too much from Charlie by way of technique. He didn’t want to talk to any great extent about the technical side, he was more concerned with mood. He did a Russian set with figures and buildings all tilted. Because he believed that in giving a tilt to any line – taking it off the parallel – you create what he described as a thrust. In other words it was a dynamic shape you were creating rather than a static shape. If you draw a completely horizontal line for the horizon, you create a stillness. There’s no question about that – it’s flat and static. Immediately you introduce an evolute, you create an impression of movement. He was always interested in the idea that you can create depth by overlapping shapes. You can have two identical squares side by side on the same plane and by over-lapping them, without making one smaller, you can get the impression of depth – without perspective.

He had another idea that he had got hold of – you find it used in some of his temperas – he had what he called the Law of Concentration. He argued that if you looked at, say, a table, and focussed on the middle of the far away side in front of you, the lines running away from you did not converge to a vanishing point, they did the opposite. Quite frankly, if you start concentrating on that, you do get the impression that it’s coming in towards you. But when this is put into practise, it’s a bit idiotic. He also used to say your darkest part should be in the corner, so you got the sort of idea of the Turneresque vortex.

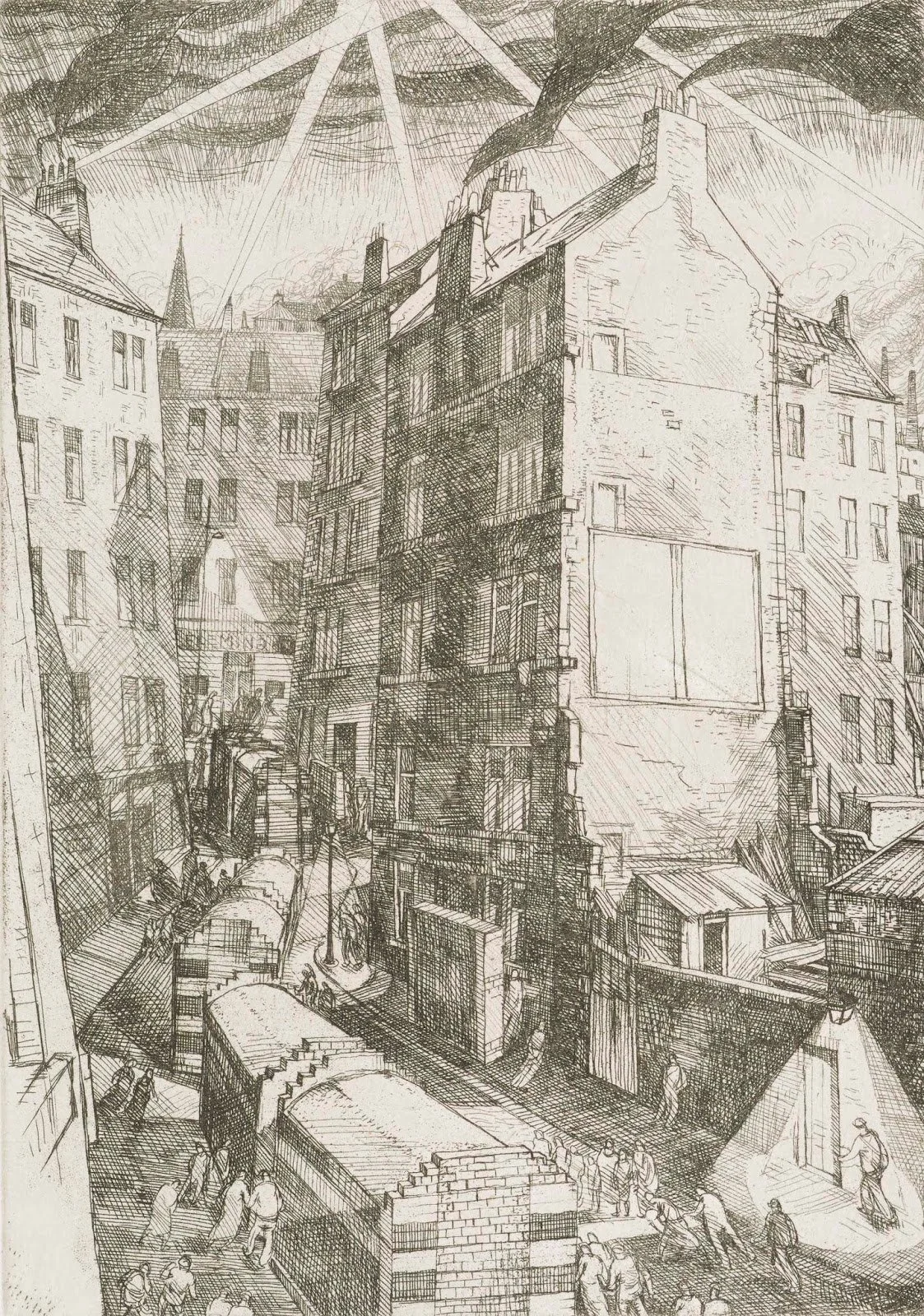

Modern Suburbia

In my Post Dip. year I did Modern Suburbia which was done from Knightswood where I was staying at the time, which was a suburb in the west end of Glasgow. I also did the Head of a City Youth, an early attempt at a Self-Portrait and one or two things like that. I was being pressed to go in for the Prix de Rome in engraving and that’s why I started off doing these very elaborate drawings of the Nativity, Gethsemane and the Trades Holiday. I also submitted The Scottish Highland Loch, there’s only one print of that. The plate disappeared, it must have been in the fire.

I submitted a series of drawings of these things, plus a life-drawing. Well, I finished second. By this time I had got my travelling scholarship and when I went south I was invited to the Royal College to meet Robert Austen and Malcolm Osborne. They quite bluntly told me that if I’d been at the Royal College I would probably have won it but they said ‘You know, people don’t do big plates like that’ which I thought was rather funny because I had done it. However, I was invited to stay in the Royal College to use the studios because at that time I was copying Dürer’s St.Anthony. I was going there every day and met some very interesting people – Leslie Brammer, for example. He did a marvellous set of etchings of the Potteries – a really superb etcher.

With regards the subject of these religious plates, the current mode in the art schools at that time was a period for so-called composition. There was a monthly composition with a criticism by staff afterwards and before the whole class, and the subject was always laid down. Jacob wrestling with the Angel, The Fiery Cross or the Agony in the Garden, among others. Augustus John’s most famous early painting The Brazen Serpent, and it is still hanging in the Slade, was a summer composition. One of Stanley Spencer’s first was The Nativity. They never said to you ‘Go out and do the Castlegate Market or something like that’. You always had to do religious subjects and so it was quite natural to think along these lines. This explains why the Augustus John and Stanley Spencer above and my Gethsemane have religious subject matter.

There was this hierarchic situation, where religious subjects were at the top, historical subjects in the middle and at the bottom were landscape and still-life. Just as watercolour was always below oil and of course print-making was below watercolour. And this is why, by this idiotic system, you charged, say £50 for an oil painting and 2 guineas for a watercolour and you only charged a guinea for a print – that’s what I was getting to start with and I thought I was being well paid. I suppose size had something to do with this rather stupid assessment.

When I went to the Continent on my Travelling Scholarship, I was away for a full year. I went first to London and spent three months there. Courtesy of Malcolm Osborne, the Professor of Etching and Engraving at the Royal College, I spent most of my time copying the Dürer and having finished there I moved over to Paris, where I looked at the Degas’s and various other French masters. I had a great enthusiasm for Degas then, and still have. I didn’t do any drawing in Paris at all. I spent most of my time doing the galleries. Another artist who interested me at that time was J.E. Laboureur, who was one of the few French engravers I admired along with Charles Meryon. Most of my time was spent looking at the print-sellers’ boxes along the quays and reading Shakespeare. I used to sit in the cafes at night reading Shakespeare out of an ‘Everyman’ book. It was the first time that I had read Shakespeare other than at school and enjoyed him, and I was also reading G.B. Shaw and Aldous Huxley in Tauchnitz editions. Then I went down to the south, to Avignon and I worked round there. I really started to draw then. Previous to that I had been looking. Showing how ill-coordinated my Art History was, I actually arrived at Santander in Spain where the famous Altamira caves are without knowing that’s where they were. I was very interested in prehistoric art too – a sad loss.

St Gimer, Carcassonne

After working in Avignon and Arles, I made several drawings at Les Baux. I remember seeing a drawing or an etching by James MacIntosh Patrick of Les Baux and I was fascinated by it so I decided to go there. I then went west along the coast. I drew one or two drawings of La Ville, Carcassone and one of the church – St.Gimer.

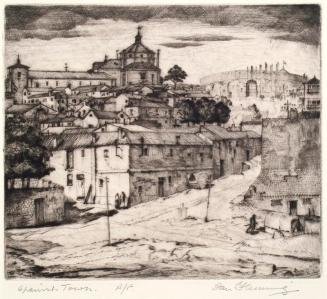

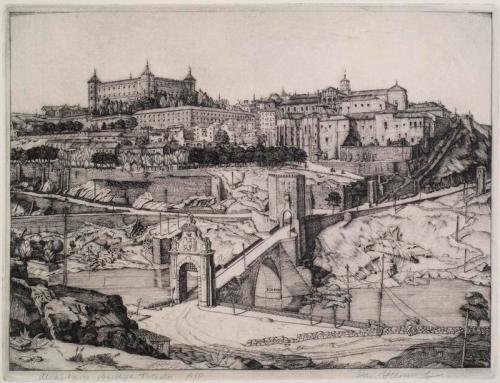

Then I went into Spain. I was absolutely fascinated by El Greco. That’s why I eventually finished up in Toledo, where the Casa del Greco is. I went to Madrid, Seville, Granada, to Valencia and to Barcelona but I had been away nearly a year and felt by then it was time to come home.

I was very disappointed in the Grecos because they were nearly all portraits and nearly all the same. The same colours, brown, reds and purples. The thing that did impress me, in the Church of San Tome in Toledo, was the famous Funeral of Count Orgaz. I was also very impressed by the Prado with many fine Grecos, Velasques and Goya – seeing them in the original for the first time.

Spanish Town

drifted on to dry point

When I came home I went to the College of Education. I was the first secretary of the SRC from the art group. I took the Board of Education examination. Previous to this I had won a scholarship to the Royal College but I turned it down because I felt I had been at it long enough, since it meant three years in London. It was during this time I finished the Gethsemane plate and made the changes that you see. I had a studio at home by this time, where I used to work in the evenings right up to about two in the morning. I found that I could work better in the quiet of late evening. In the Gethsemane drawing, the trees which I used to simulate flames were rejected in the engraving because you couldn’t see through to the landscape. In any case, it’s a damned sight easier to draw trees without leaves than trees with leaves, especially when you are engraving. The first thought was wrong – to try to incorporate a tonal scheme into a linear. It doesn’t matter if it was a good thought in the first place, it was wrong for the medium.

E.M. Lumsden was impressed with Gethsemane and when he was on the Awards Committee of the RSA he asked them to look at this print with a view to giving me the Guthrie award, Sir Frank Mears, who was the President at the time, was almost appalled. He turned round to Lumsden and said ‘But who ever saw Jesus Christ in trousers?’ and Lummy said ‘And who would ever imagine him without them?’ Several years later it appeared along with work by members of the Society of Artist Printmakers in a big exhibition in Paris and the French government purchased Gethsemane along with Willie Armour’s wood engraving, Old Davie.

Gethsemane

When I came back from my year abroad I found that line engraving was a bit arduous for some of the drawings I had brought back – and I automatically drifted on to drypoint, which is of course a form of engraving – working up the drawings I’d done abroad. I only developed a certain number of these drawings, possibly because I was beginning to get a bit suspicious about this topographical side of my work – picturesque views.

Alcantara Bridge, Toledo

Charlie Murray always emphasised this ‘mood’ idea and that there was no point in being purely topographical. His main criticism of me at that time – in particularly of the print of The Alcantara Bridge – was ‘too damned factual – not enough mood’ and he was right, it is too damned factual. This is what I felt about engraving – you couldn’t get this sense of mood which he got in his drypoints and etching and I think that might have been one of the reasons why I drifted over to drypoint – because there is greater opportunity for tonality and also for mood in drypoint. In engraving you get a positive and rather static line.

That was one thing that surprised me when I was studying the Rembrandt prints in the Rembrandt’s Huis in Amsterdam recently, practically every one, which I had imagined was pure etching, was etching, drypoint and engraving. They were absolutely marvellous. You don’t get the same idea looking at a reproduction in a book but in the actual prints you can see the drypoint quite clearly. This mixed medium gives a richness of line.

the first etching I ever did

One thing that was quite obvious from the volume of work that was there in Rembrandt’s Huis, was that Rembrandt must have handed quite a bit of work over to professional engravers. You actually see an engraving of the workshop and there is a whole lot of ‘bods’ working away like billyo. This is why I find it very difficult to associate myself with the procedures of today. For instance Hockney dashing off a thing and getting someone else to print it. The same with Paolozzi, who takes it even further. It is a collaboration, but I had been brought up with the idea that I had to do a print by myself from initial drawing through to printing the final print. In my day the whole ethos was that you had to do everything from start to finish. You should not use a photograph – you should do this or that, too many rules in fact. I was using a ruler last night on an etching plate and I remembered going for an interview for a job to Liverpool School of Art after I qualified (I was also coming up for an interview at Glasgow at the end of the same week so naturally I was hoping I didn’t get the Liverpool job.) I turned up with a Still-Life which I had done for my Diploma – with square patterns in it. The Chairman of the Governors said ‘Mr Fleming, did you use a ruler for that?’ and I said ‘Yes’. He said, ‘You know you shouldn’t use rulers.’ There was this attitude that you shouldn’t use mechanical aids. You must have tremendous courage to draw a straight line freehand, just like that. I wonder how many set squares, ‘T’ squares, rulers, Ian Howard uses. He gets all those elaborate structures, lines this way and that way. They wouldn’t be possible without these mechanical aids and I think they would lose something of their quality drawn freehand. But this was the hard and fast academic attitude rules which had to be obeyed, or ignored at your peril.

I always regarded Art as being an expression of the individual and his emotional reaction to the visual world and the artist tried to find the best means or media for this expression. I was always fascinated by a sharp point, I liked a line. The way you cut wood, you have to be precise about it – you cannot have a dithery piece of woodcut or a vague line in engraving – you’ve got to be absolutely precise and know that that line goes from there to there and there is no dubiety about it. This is one of the disagreements I had with Bobby Blyth. He used to judge life-drawing on an entirely different basis from the way I would judge life-drawings. He used to think that anything that was vague or indeterminate was sensitive. Which is a load of codswallop, but he was right about so many other things. It was all the sort of genteel stuff that comes from Raphael, and Bonnard, too, has what I’d call that spongy line. Edinburgh fell hook, line and sinker for this and for colour, and if you had colour and mass, line went out the window. Did not Willie McTaggart in a television interview say that Etching was quite meaningless to him?

Botanic Gardens, Glasgow

When I was appointed to the staff at Glasgow I was offered the etching job but I didn’t take it. Then I was given the opportunity to teach the third year drawing and painting. Etching was peripheral to the activities of the school.

The pay wasn’t that good anyway. Mind you, the pay for the drawing and painting job wasn’t that hot either. I started off with £120 per annum and £30 for lecturing. At first it hindered my own work because I had to prepare a series of Art Lectures. I was literally one lecture ahead all the time. Such work as I was able to do was not painting but was largely etching and engraving because I could do that in my studio at night. Most of the things I did from the foreign drawings were drypoints. The first etching I did appeared round about 1935.

Glasgow School of Art

By this time I had met Willie Wilson. We were both members of the Society of Artist Printmakers. Because it was centred on Edinburgh most of the Committee were from Edinburgh or Glasgow. The Society of Artist Printmakers was actually formed in Glasgow in 1921, by the students of the Glasgow School of Art – people like Chika McNab and Ian Cheyne. It operated first in Glasgow from this student body. Josephine Haswell Millar, who took etching at that time, was one of the founder members. I think Agnes Miller Parker was another. But then E.S. Lumsden arrived on the scene and he became President and took the whole thing over to Edinburgh. He had recruited a large number of people from the south, Graham Sutherland, John Copley, who was a very, very fine black and white lithograph man, and R.G. Dent, who was the Head of Cheltenham College of Art. Because there were so few of us up here in Scotland and because we couldn’t get people from the south to travel up for committee meetings I was made a permanent Member of the Council of the Society. Willie Wilson was the permanent Secretary. Ian Cheyne was the permanent Treasurer. Ernest Stephen Lumsden was the President. He was very dictatorial. It was more or less through these connections I turned to etching.

As far print making is concerned, two people influenced me more than anybody else, that is apart from the usual influence on had from Dürer, Meryon, Bone and Whistler. The two people were Willie Wilson and my mentor, Charlie Murray. Willie Wilson trained under Adam Bruce Thomson who took the etching class in Edinburgh, while he was working in, I think, Bartholomews the map firm. And he had gone to classes at Edinburgh College of Art at night and had become interested in stained glass and etching. Willie was a terrific influence. I admire everything he did and as far as I am concerned he was the best etcher of us all. He is also a very fine watercolourist. His Paris water-colours are as good as anything done there. Some of his work done round Eyemouth and Burnmouth is really superb.

School at Elgol

After we had been introduced to one another we used to show one another our work. I would go through from Glasgow in the evening at 7 o’clock and he would meet me. A fortnight later he would come through to Glasgow. By that time, he was working in stained glass with a firm called Ballantynes. Then his etching brought him into some considerable prominence. He was exhibiting at the RSA. I first exhibited at the Glasgow Institute in 1928 and at the RSA about 1930 – always prints. It inevitably followed that we started to work together and we went off sketching together. We did Loch Long, Skye, Elgol and the Fife Coast. I hadn’t done any harbours up until then but I went with Willie to places like Largo and St. Monans. I literally visited every harbour between Leven and Ardersier.

When the two of us were down in Kirkcudbright, I introduced Willie to Sivell and Sivell had previously noticed this big etching of Willie’s in the RSA and Sivell said, ‘Oh aye, you did thon big thing of Coruisk in the Cuillins – fu’ o sound and fury and signifying damn all’. That sums up Sivell. He was always putting people down. It was ‘Me and Botticelli’. ‘Aye’ he said, ‘It’s like a Botticelli is all right. Me and Botticelli have got the same way of doing things. Come tae think of it, it might even be better than Botticelli.’ He had a terrific egotism which showed itself in his remarks to Willie. Willie Wilson was a very considerable artist – his reputation is in a limbo at the moment, but I’m sure he’ll come through.

The general aim in etching then was for ‘visiting card precision’ which implied you had a perfect ground. There was one fellow in the School of Art who used to tip-toe into the etching-room, so that he wouldn’t disturb the dust on the floor, lay his plate against the wall with its face towards the wall. He’d then put the lights on in the heater and wait until everything had settled. He’d then tip-toe in again, put his plate on the heater and lay his ground. This was always a bit of a joke between Willie and I. He said to me one night, ‘I don’t seem to be able to get the sort of quality of ground you and Willie Wilson get – the feeling of tonality. What do you advise me to do?’ I said, ‘Walk into the etching room, lay your ground, put the plate on the floor and jump on it.’ He looked at me as if I was completely crazy, so I took pity on him and said, ‘Look, what I’m trying to say is, you should be master of the ground, not it master of you.’ We even used to use sandpaper on the plate to give foul biting, the equivalent of something like aquatint. The etchers of that time were obsessed by the cleanliness of everything. Old Lumsden would have been horrified if a scratch appeared on his plate. Nowadays with open bite, lift grounds and photo-sensitive grounds and what have you – anything goes.

At that time etching was just about to be clobbered. The Bell Publishing Company asked me if I would do a series of etchings for them. They gave me a list of subjects to do. I could either go and visit these places or work from photographs. This to my mind was demeaning, so I turned the whole thing down. What they were wanting were things like the Brig of Balgownie, Stirling Castle and the Brig of Turk – purely topographical. Unfortunately that was one of the great weaknesses of etching at that time. I think this is one of the reasons why etching did go out of favour. The Scottish and British etchers all thought that you had to go abroad, to France or Italy, to work. Whistler went out to do his Venice set and yet most people would agree his greatest prints were his Thames set. I couldn’t be bothered with this topographical stuff. I felt that etching and engraving, and painting for that matter, should say something. I think this derived first of all from my interest in Japanese prints, where there is a lot of mood.

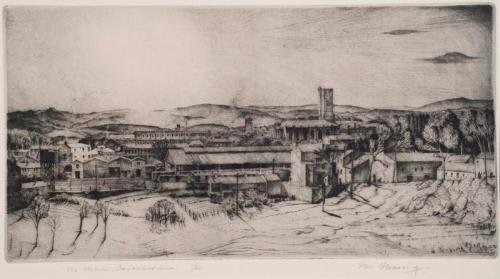

The Station, Carcassonne

In recent years I was going back in the train to Glasgow from one of these Varnishing Day dinners at the Academy. I had embarked on the series of Sunbursts. On the train Mary Armour said to me, ‘What on earth induced you to come to these Sunbursts – you have never done anything like that before? You were always interested in harbours.’ Well of course I was interested in harbours, but I’ve been interested in other things and you can look back to my very first prints – to the Parkscape, Rain and Sunshine, the Mill with the moon, the Sunrise in Galloway, in the drypoints of the Station at Carcassonne and Avignon from Villeneuve you have it again – you’re facing right into the sun. I have always been interested in seeing things against light – this circular movement too. Macintosh Patrick, who was in the year ahead of me at Glasgow, came up to me and said, ‘Always know an Ian Fleming,’ this was during what we might call my harbour period, ‘There’s always a life-belt in it.’ Here you have this circular thing again! – a sun or moon. At the beginning of the war, I was exhibiting in Glasgow, with a Glasgow group, and a Jewish psychiatrist, a refugee from Germany, was rushing round looking at the paintings and he said to me, ‘I’ve been looking at your paintings – psycho-analysing them and you’ve got a vaginal fixation.’ I looked at him and said ‘What do you mean?’ ‘Well,’ he said, ‘There’s lots of circles.’ From that moment on I was very suspicious about psychiatry.

Shelters in a Tenement Lane

I left the School of Art in 1940 for War Service. I tried to get into the army but was rejected because I was in a reserved occupation. Eventually I got into the Police War Reserve and went through the blitz in Glasgow in 1942. A number of sepia wash drawings were made – one is in the People’s Palace, Glasgow.

In the etching, Air Raid Warning, with the two policemen I deliberately tilted up their faces and tilted the police box to give the idea that you were looking up, from down below the ground in a shelter. The Glasgow Tenement was of a shelter in a tenement lane and that was really done from memory, as were all these blitz plates. Except, that is, the Bomb Crater, Knightswood which was just across the road from my window. I was always very concerned with memory drawing and I introduced it to the teaching at Glasgow. Because I believe all drawing is an act of memory. Even if you are drawing from a model, the very fact that you look up at the model and then put your head down to indicate the lines on your paper is an act of memory, even if it’s a very short act.

I got out of the Police, because I wanted to see what was happening in Europe. It was a quixotic gesture but it did enlarge my experience.

You have to be able to draw a human figure from memory. These war drawings, the water-colours were all done from notes on the back of notepads. When I landed in Normandy I was carrying sheets of drawing paper in the bottom of my mapcase. Whenever I got the opportunity, whenever we got a place that had a little stability, I was able to snatch some time and do some drawings. I didn’t do anything, by way of etching, of these things. The so-called war prints are all of the blitz in Glasgow.

But you have to go through a period of intensive study of visual facts before you can rely on your memory.Every one of the trees in Gethsemane was drawing in isolation.The actual structure was taken from the famous Fossil Grove in the Whiteinch Park in Glasgow.I introduced the fossilised trees for the tree roots.When I was in my Post Dip. year I used to go home every night with my sketch book and draw what the class had drawn – trying to improve my memory.When Willie Wilson and I were up in Skye, we would take the watercolours we were doing to a certain stage, then go back to the hotel and in the evening we would

Pocra Quay

During the years after the war, there was no etching of any sort being done anywhere. The Society of Artist Printmakers just went into oblivion. All I did in those years was the little thing of Hospitalfield which I did as a Christmas card.

The trouble at that time was that you were hidebound by what we called ‘visiting-card precision’, even in etching. It was only after I started to work up here in Aberdeen in 1954, when we decided to develop printmaking at Grays that I took up etching again. The etching press was set up in the room above the archway between the Art Gallery and Grays. It was then that I did that big Moonlight Harbour. I decided that the only way to do it was to sit down and work out some of the problems that I’d forgotten about because I hadn’t done etching since the war. I had done no aquatint before that. I also started the Pocra Quay, 1957, but it didn’t get finished till much later. Then, when we moved over to Garthdee, we decided to develop Printmaking, firstly in the Design and Crafts Department, then in the Drawing and Painting Department. (Note 4)

take off the old jacket

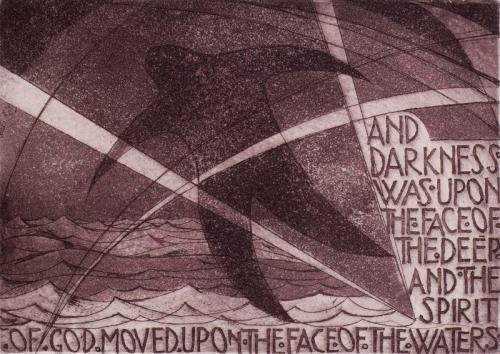

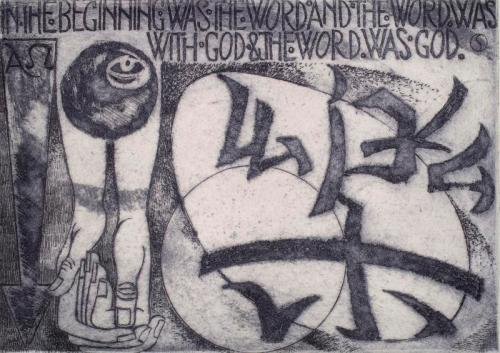

When I came down here to Peacock I thought, ‘Well fair enough, I’ll have to take off the old jacket and get busy again’ and I started off on the The Creation Series. There is a small etching from very early on of that subject. Every student had a bash at it. It usually started off with moons and suns and since in composition, you had to have two figures, it was usually referred to as ‘Adam and Eve’. Everybody seemed to find it a challenge. Paul Nash did a series – he divided it into the days. Charlie Murray had a shot at it and we all had a shot at Resurrections. There were certain subjects which became very popular. When I first started, one of the first colour woodcuts I did, was The Bridge of Isla in Perthshire – because everybody did bridges. This all sprang from Frank Brangwyn who did all the bridges of Europe in a series of powerful and large etchings.

Creation Series: And Darkness

Creation Series: In The Beginning

The Creation suite (Note 5) was used as the first exhibition in Peacock’s shop in Marischal Street. It was actually shown in the RSA and sold so many copies, that I made over £1,000 on the prints. It caused quite a row in the Academy because the sales attendant kept sticking big red markers all over the print. The glass was absolutely peppered with red spots – a case of academic measles.

When I had finished the Creation I was struggling with the idea of doing something abstract and that’s how I got on to the Comment series. An abstract to me seemed too dehumanised. It’s not the particular method that you are using, but the effect in the end that’s important. If you are doing a print of any sort, while it’s a multiple, it has got to be a multiple that says something. It’s not enough to say simply, ‘This is a lovely bit of texture’. This is why I took up the question of the Comment series. I felt that etching or a print should say a little bit more than either the simple representation of a scene or an interesting arrangement of abstract shapes. Or effects of mass or texture. It’s fair enough for an abstract artist, one begins to ask if that is enough. I can understand why music can be an abstract art. The representational stuff, such as Ketelbey’s Persian Market, is usually inferior.

Music gets right inside you and affects you emotionally. I am prepared to accept up to a point the argument that colour, or shapes can affect you to the same intensity. I don’t totally believe it. Even colour is always outside you, whereas sound is inside you. There’s not the same intensity. And a black and white abstract arrangement of shapes is of rather cerebral interest. The visual side must always have some parallel to the representational – it must appeal up there in the brain as well. I am quite prepared to accept the criticism but this might be a deficiency in myself.

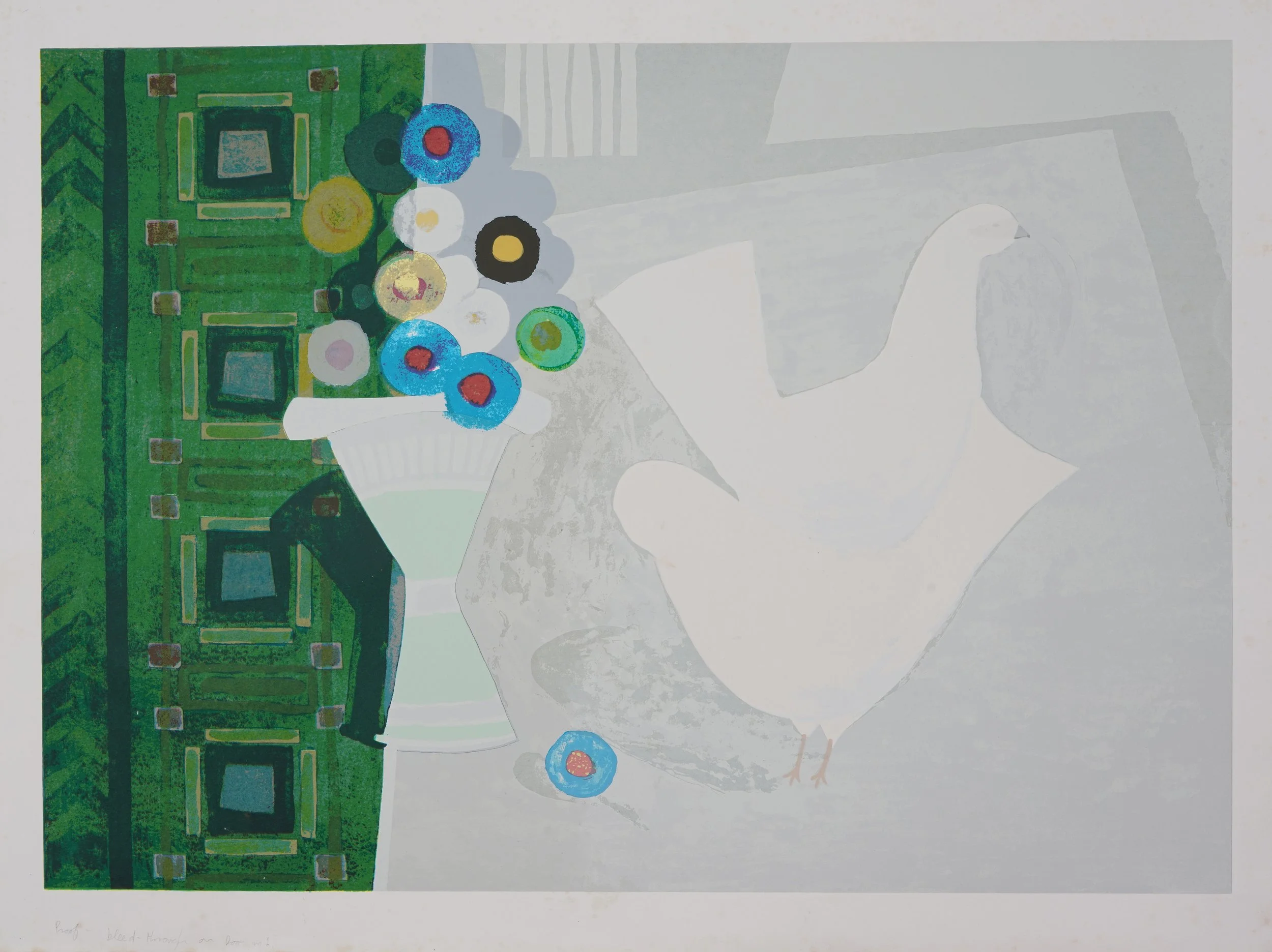

Comment Series: The Meek Shall Inherit..

Comment Series: The Face of Violence..

Comment Series: Little Boxes

Comment Series: How Original!

The silkscreens were largely conceived as a watercolours and I decided I would like to give them more permanence. The reason I asked Malcolm McCoig to print was because he seems to get all sorts of effects in silkscreen and when I told him this, he took it as a sort of challenge. He went to great trouble, doing all sorts of separations and trials. It became almost a game to see what would result. That’s how we produced The Preening Fantails – it was a collaboration between myself and Malcolm. In all the other silkscreens, I’ve done the separations myself. Malcolm has this terrific knowhow – he is the supreme silkscreen printmaker and an original if ever there was one.

The Preening Fantails

I don’t know why I started using lettering in my prints. When I was over in America I was very interested in Ben Shahn. He has been dismissed rather summarily as being a social realist. But his book on the ‘Beauty of Lettering’ impressed me. He used lettering a lot and he had a comic way of thickening bits and almost using them as part of the drawing. When I was in Manchester Central, the capital of New Hampshire, I went into a workshop and there was a girl who had obviously been influenced by Ben Shahn and had used lettering her paintings beautifully in a very integrated way and I decided to investigate the possibilities of this. I used it first on Christmas cards and such like things.

I couldn’t be bothered with lettering when I was a student but David Hodge, in Grays here, was an expert letterer. I explained to him that I couldn’t be bothered with lettering and he said, ‘What’s your trouble?’ I said, ‘I don’t know.’ He said ‘One thing you’ve got to remember is, it’s not the letter itself you should be concerned about, it is the space between the letters.’ I suddenly saw this was true of Ben Shahn, Edward Johnstone and David Jones, who used lettering alongside their engravings. I realised that these chaps were all concerned with the space between. They were interested in what they could do with lettering without being too pedestrian with the Trajan Column and all the other traditional styles.

Images can be used as symbols to convey something, like words. In The Bell Jar, I used the image I had got from reading Sylvia Plath’s poetry. I got the visual idea of this woman under a bell jar – as she imagines herself. Then I got the idea of the shape that everybody has when they are dreaming or depressed, of corridors and so you get the figure running through the corridors. All this came as a result of reading her letters and poetry. I don’t know if you would call that illustration or what you would call it, but in my book it is a valid excuse or stimulant for picture-making or printmaking.

Glasgow Triptych

Ian Smith and Bill Baxter came down to look at the Glasgow Tryptych. I was telling them that I hadn’t proceeded with it because I felt the left hand side was out of scale. There was, therefore, a sort of ambiguity about the whole triptych. I was concerned about the unity of scale, so I scrapped it and did what you see now and which has something of the same scale and therefore you get a homogeneity that you wouldn’t otherwise have. The plate I rejected appears as a singleton in another guise, Glasgow Kids Playground.

…..& get busy again

Finally in this interview, I feel strongly that I must say something about Peacock Printmakers, after all this is a Peacock sponsored show. I was appointed Chairman in 1974, and in accepting this with enthusiasm I regarded it as an honour and an opportunity to resurrect myself from the dead, so to speak, as a retired Art School Head and to identify with the young, and the upcoming; to engage in an activity that was all important to the art world of Aberdeen, to associate myself, with diffidence I may add, to a venture that was challenging and so worthwhile – a venture long overdue and made a reality by the vision and energy of two men and one woman, namely Arthur Watson and Malcolm McCoig, plus the exceptional experience and ‘know-how’ of Beth Fisher. I often wonder if the rest of Scotland, and especially the Lowland belt, realise what is happening up here in Aberdeen. Oil has helped, but it is not the whole story – civic pride, individual dynamic, an Art Gallery well above the normal, coupled with a Civic Theatre now bursting at the seams, and of course Artspace and Peacock Printmakers. Yes! The Arts in Aberdeen are in good nick and long may it continue.

Glossary

Relief

Printing method in which lines are cut into the surface of a block of either wood or lino. Ink is then rolled onto the surface of the block, leaving the cut areas uninked. Paper is laid on the inked block and the ink is transferred from block to paper using pressure, either from a press or by hand burnishing.

Woodcut

Method in which lines are cut into a plank of wood using a range of knives and gouges. Printed relief.

Linocut

Method in which lines are cut into a piece of linoleum using a range of gouges and v-cutters. Printed relief.

Burin

Metal tool with a lozenge-shaped point, used to engrave lines in wood or metal.

Wood Engraving

Method in which lines are engraved into the end grain of a dense wood, such as box, with a range of burins and other tools. Printed relief.

Keying

The registration of different colours in multi-coloured print.

Intaglio

Generic term covering line engraving, drypoint, etching and aquatint. Printing method in which lines are incised into the surface of a plate – normally copper, zinc or steel. The plate is covered with ink, and the surface is polished, leaving ink only in the incised lines. Damp paper is laid on the plate and run through a press under great pressure, which transfers the ink from plate to paper.

Burr

Minute shaving of metal raised by a drypoint burin. In a drypoint the burr, which holds ink, is left, and prints a soft velvety line, while in an engraving, any burr is removed, leaving a crisp hard line.

Line Engraving

Method in which lines are incised into the surface of a metal plate using a burin. Printed intaglio.

Drypoint

Method in which lines are incised into the surface of a metal plate using a steel or diamond point. A burr is raised which holds ink and prints a soft velvety line. Printed intaglio.

Hard Ground

A wax based substance which is melted on to a plate to form an acid resistant layer when dry. This layer is drawn through, using a needle to expose the bare metal of the plate. When the plate is immersed in a bath of acid, only the areas exposed by the needle are attacked.

Soft Ground

A ground which remains soft. A sheet of paper is laid on the ground and a drawing is made on the paper with a pencil. Where the pencil has pressed the paper into contact with the plate, the ground is transferred to the paper. When the plate is etched, a granular pencil-like line results.

Etching

Method in which a metal plate is coated with an acid resistant ground. This ground is drawn through using a needle to expose the bare metal of the plate. When the plate is immersed in a bath of acid, only the areas exposed by the needle are attacked. The longer the plate is left in the acid, the deeper the line, the more ink it will hold and the blacker it will print. Printed intaglio.

Foul Bite

An area of irregular tone formed when acid bites through pinholes in an imperfectly laid ground.

Aquatint

Method in which a metal plate is covered with a fine resin dust. This dust is melted to form an intricate pattern of acid resistant particles fused to the plate. Any areas which are to be left white in the finished print are painted out with an acid resistant varnish. The plate is immersed in a bath of acid which eats away the exposed metal surrounding the resin granules. A full range of tones from white to black is obtained by alternate etching and painting out: the longer the etch, the darker the tone. Printed intaglio.

Open Bite

Method in which a large area of plate is exposed to acid and etched, normally quite deeply. Because there is no network of fine lines or aquatint resin to hold the ink, an area of open bite prints as a pale to mid tone, becoming darker towards the edges.

Silkscreen

Printing method in which fine mesh is stretched on a frame. Part of the mesh is blocked by a stencil. Ink is pushed, with a rubber-bladed squeegee, through the remaining areas of open mesh onto the paper below. Stencils can be made by a wide range of techniques using hand painting, cutting and resists.

Separations

These are made by painting with opaque paint on clear acetate. A different separation is made for each colour to be printed, and a stencil is made from it by passing light through the separation onto the screen, which has been given a light sensitive coating. Separation can also be made photographically.

1986 Ian Fleming recorded interview with Malcolm McCoig

MM: Perhaps you could tell me about first being introduced to Peacock.

IF: When I first became acquainted with the idea that it was proposed to have a Printmakers Workshop in Aberdeen, I rather felt very, very pleased that ex-students of the Art School and members of staff should get hold of this idea and try and pursue it.

I had had knowledge of one in Glasgow but I never visited it. I actually went out of my way and visited the Edinburgh one and I was rather impressed, although at that particular time it was really a shop in The Netherbow in Edinburgh.

The next thing was I think it was you who actually told me about a meeting that was to take place in the Art Gallery and would I come along? I went along and I was extremely impressed by this lady (Note 6) who had come up from Glasgow who was obviously American who outlined the whole idea of a workshop and how to start it. I was extremely impressed by the way she divided off all the various aspects of it such as funding, how to get money out of the Arts Council, what we would be required to do, and one of the major problems seemed to be the finding of a proper building, the stocking of said building, and getting a mortgage or some other money to run it. It was all very impressive and very optimistic.

But counter to my usual reaction to these things, on afterthought, I was extremely pessimistic. I didn't think that we had the necessary know-how up here to be able to carry it through.

The next thing I heard was that they were going to have another meeting at which they actually formed a committee and got down to it and as far as I was concerned I was extremely surprised when two representatives from the new proposed workshop visited me one night and asked me if I would be Chairman. One of them was Ian Guthrie, the Secretary to start with - Secretary and Treasurer. That painting of his is downstairs. I don't know who the other man was. Do you remember?

MM: I can't remember that, Ian. I can't remember how we got you involved. The important thing was that the reason that printmaking actually started in Aberdeen is that you helped to introduce it into the school. Otherwise it would never have happened. It was the frustration of students leaving the college here, printmaking students, who had nowhere to go, (that made it happen). In fact you were the start of it all.

IF: I couldn't say that.

MM: I know you couldn't say that, but I can say it.

IF: Then I went on to find out just precisely where I could help, Now, I happened to be a member of the establishment. As an ex-President of Rotary, as ex-head of the Art School, as a member of the Royal Scottish Academy, I had obviously covered a wide range of art interests and there was a certain amount of prestige attached to that at that particular time and I was therefore able to front the whole situation, but as far as I was concerned that seemed to be the entirety and I then realised that the new director, Arthur Watson, was the man who seemed to be supplying all the initiative. There was no question about that. That is absolutely true.

MM: One of the reasons we asked you to be Chairman (it’s funny) was that no-one ever came into our head that it would be anyone else. I know you listed all of the things that you were part of. We kind of knew that, but as young lads then, we weren't too concerned about that. We just felt this is the right man, a really well known printmaker, plus you knew a lot of folk and we thought we could use you, in the nicest possible way, and also I think it inspired you to do things. It came at the right time. You were just about to retire.

IF: I just had retired.

MM: You just had retired, so it seemed that it was just ideal.

IF: Well, when I was invited I asked Cath, ‘do you think I should get involved in this?’( Note 7). At that particular time I had a whole lot of projects in mind, exhibitions etc. etc. and she said, ‘well, you better get on’., and when I decided that I would get on, I was rather excited about the whole idea and that's why I took off my jacket and really got down to it. We did a lot of research, oh! and another thing, this shows how carefully everything was planned. We were hunting for premises, we had actually divided the town into areas and we took a one mile radius from the Monkey House to make it accessible, and each individual was meant to perambulate around his section and try and find out where the best premises were. We had already turned up the Police place down at Peacock.

I thought that people wondered why we called ourselves Peacock instead of Aberdeen Printmakers Workshop. I pointed out that there was a listed building down Peacock's Close where we made our first residence. A famous dancing master called Peacock had actually worked there and so there was a certain tradition, and we decided rather than use the word "Aberdeen", that Peacock Printmakers sounded rather nice.

MM: In fact we decided that in one of the lounge bars of the Caledonian Hotel.

IF: That's right. I was going to start talking about how we held meetings in the lounge bars of practically every howff in and near Union Street, and that's where we actually got started. Arthur and I went down to various roups, especially of defunct print works, in order to collect the initial furniture which was necessary to set up printmakers. We begged, borrowed, and stole. We literally stole stuff from across the road. I thought that this is getting too bumptious as far as I was concerned. That's why I scrapped it.

Another thing that I could say was that we started off with a committee of 15 to 20 and I personally found that this was too much once a month and we were not in the initial stages getting to the core of the matter. Because things were developing too fast and we were trying to get overdrafts from the bank and you had to be there all the time practically, and all this work devolved on to Arthur Watson, the director. I think on my suggestion we should meet once a week, Tuesday, and the committee should be reduced to five, with the director in attendance, but without a vote.

Concurrently with that, we had constant interviews with lawyers and architects, and constant interviews with various people trying to get funding that was necessary, and again Arthur played a terrific part.

MM: I think you must of too, because it was a kind of duet the pair of you were at that time. I wonder what you think, Ian. You'd been retired for only a couple of years and here you were spending a lot of time doing a lot of extra committee work and running about town. You must have felt it was worthwhile. Did you think it was time wasted, was it frustrating?

IF: No, I thought it was a marvellous idea. In view of the fact that I had felt very strongly about printmaking, and had always been very very conscious of the importance of printmaking. As a matter of fact, this month I am speaking at the Scottish Art Historians conference. It's to be held in the Modern Gallery. I can't remember the date. Sometime in October. I'm supposed to speak on the art situation in the 20's and 30's in Glasgow. I just jotted down a note on the importance of the Society of Artist Printmakers who were then operating and were the only people in Scotland who were operating. Largely speaking they kept etching alive through people like Willie Wilson and myself and one or two others, which started to blossom, because the influence of people like Hayter (Stanley Hayter 1901-1988) and Gross (Anthony Gross 1905-1984) in London began to percolate up to the frozen north, but in keeping with what was actually happening in Scotland with people myself who were still operating.

That's one of the main reasons why I opted to start it again in Gray's and was so enthusiastic about it. I can also say that I was tremendously impressed with the potential of silkscreen when Peter Perritt came up, but it was only - and this may sound surprising - at the level of fabric, of textiles, and believe it or not Christmas cards. It was a nice way to do it. It was only when Malcolm McCoig arrived on the scene that through perhaps the influence of Bob Stewart that it suddenly dawned on me that there was a wider potential for silkscreen. So therefore when you arrived at Gray's and you produced various people you were God's gift to Peacock. (Note 8)

MM: I don't know about that.

IF: I think so. I think you're one of the most original artists to come out of Scotland from the 40's right through to the present day. I'm not so sure if all these whiz-kids who are running around will live because some day somebody's going to discover you.

MM: I'm still waiting on that.

IF: But they will.

MM: That's nice to hear you saying that, but talking about printmaking, I think you were obsessed about the printmaking. When I read about how you spent a post diploma year in Glasgow, and then the obsession was carried on when you introduced it in Hospitalfield. It seemed right that you were the guy who was actually going to do something about it in Aberdeen. Now you introduced it in the school, and all of a sudden you had a member of staff who was obsessed about printmaking - a different medium, right enough, but that doesn't matter, it's still the printing thing which gets into you, under your finger nails, getting filthy and all that - and then you had a student who was obsessed about printing who was Arthur, and it seemed to be that team of three, finally, without blowing our own trumpets, that actually helped to make the thing go. If you don't have those kind of obsessions the thing never gets off the ground. I think from your point of view it must be satisfying to think that Aberdeen is now known as the printmaking capital of Scotland.

IF: I'd agree with that.

MM: We've now got two guys in post-graduate printmaking this year in the school who have come up from Glasgow to do it. It's quite interesting that the eyes are now looking towards the North East as far as printing is concerned.

IF: Yes, I quite agree with that, but I couldn't write that.

MM: I know. We don't need to worry about what we're writing. I find it interesting because it becomes clearer as I go on what actually did happen. It's the old story, when you're steeped in it you don't actually know what's going on historically. It's only once you get past it and you look back you can see "oh that's the role he played and that's what he did and such and such.."

IF: But I felt that my presence there was actually helpful. I also had a very good relationship, strangely enough, with most of the people in the Arts Council, because I was prepared to accept rebuffs and try and find a way around about them.

MM: How did you find being involved with all of these young group of folk, was that not quite exciting? You'd obviously been a good teacher all of your life and the minute you get up to the higher echelons of running a school you don't see students an awful lot after that apart from complaints or worries or folk weeping or whatever it is. You seem to have a very nice rapport with folk at all levels and I wonder whether if you felt this youthfulness was quite nice not to control but to help steer..

IF: I found that most exciting. In fact I felt a relationship to you folk, in the same way as I had with MacBryde and Colquhoun, and Willie Wilson, and all these people. I had this sort of rapport with them, and believe it or not, it is only in the last two or three years that I've really felt my age. Up to that I was always surprised to discover, when looking in the mirror, that I was 60 or 65 because I never felt like it. I think what you will find is that that's what happens to you. Something inside you remains the same. It's modified slightly by age, but you're still - I don't know whether it's peculiar to certain individuals or to artists - but you're still excited enough in this creative sphere to get excited every time you sit down to do something that you like.

It's only recently that I find myself getting bored: "I've got to work for an exhibition. Oh Christ. When is it?" It's only now that I've decided that in the future after mucking around with frames and doing all sorts of things, I've decided in the future I'll damn well not produce my own frames. It's time consuming. It's nerve wracking. It's everything..

One other factor which is nothing to do with art. Every now and then, you discover that all of your contemporaries, every one of them, they're away. Your father, your mother, your cousins, your uncles, your aunties, all the people who went through art school with you, all the members of staff that you've worked with. They're either away somewhere and you don't know something about them, or they're dead. And you're working with another lot. And I think after a certain age you get this feeling that if you plunge into a situation such as you had, or I had, with Peacock, it acts as almost a spur. You begin to see things as coming alive again, in the best sense of the word.

Up to that time, when Willie Wilson died, or when I go down to the Academy for example, I don't know a single bloody person in the place. I know them, but they're not part of a creative area of my life. They're not part of that at all. Anyway, Bruce Thomson, Donald Moodie, Willie McTaggart, Bill Gillies, Hugh Crawford and all that crowd.

You see Davie Donaldson was a student of mine. He says I helped him a lot. I don't know whether you saw his catalogue where he blows me up like nobody's business. Well I was never conscious of having many dealings with Davie, but I must have had, because he insisted that this was so. All these people are different strata, but if you inject yourself into that it becomes exciting.

1. Thanks to Peacock Visual Arts and Ian Fleming’s Estate for permission to reprint and use images, and thanks to Sandy Wood and Robin Rodger at the RSA for their help and support.

2. Original interview and transcription by Anne Whyte

3. This photo is printed in the 1986 Peacock Printmakers Exhibition at the Talbot Rice Gallery, Edinburgh brochure. It is not credited, however MM thinks it was taken by Andy Dewar, on a timer.

4. MM: “When I arrived at Gray's, printmaking was done under George Mackie and was really used as illustrations for graphic projects. Main printing methods were etching/aquatint and stone lithography. I can't remember any other department being allowed to use the equipment. When Gray's moved to its new Garthdee site, Gordon Bryce, a painter from Edinburgh, was appointed in charge of Printmaking, still in the Design Department. Any screenprinting on paper was done in Printed Textiles, usually by students who took this subject as a secondary choice.

This set up continued for many years, but after the big restructuring of changing from Diplomas to Degrees, printmaking came under Fine Art, but Design students could still use the equipment. Before all this, Sandy Fraser and Derek Ashby created a small printing set up within Drawing and Painting. The former Peacock etcher and former Gray's painter, Lennox Dunbar finally took over the running of Printmaking with good part time help from Beth Fisher. Michael Agnew is the current head of department.”

5. MM: “I asked Arthur Watson about the "Comment" & "Creation" series. He said all of the plates were not copper (they were too dear) as he used a lot of much cheaper zinc ones.”

6. Beth Fisher

7. MM: “Cath Fleming was always there for Ian, backing him in all that he did and encouraging him to mix in with the "young guys". She always appeared in his Christmas cards - as did his Fox Terrier. Latterly I printed all his cards, which was the same format each time. A pen and ink drawing on a sheet of A4, printed in a single colour, often on a toned piece of card, folded in a concertina format. That is where I first encountered his use of "Ben Shan" type lettering (later used to great effect in the "Creation" & "Comment" series) Cath had a very calming effect on all she met, having a very typical Glasgow humourous and sensible approach to life, maybe not taking it all that seriously? She had a large marvellous collection of Staffordshire flat back ceramics which I think she donated to Aberdeen Art Gallery. She was a delight to have known”.

8. See article on Malcolm McCoig in Art-Scot Issue 1