The Edwin Austin Abbey Trust Six Scottish Murals

Between 1961 and 1988, The Edwin Austin Abbey Memorial Trust Fund for Mural Painting in Great Britain funded six Scottish murals. Jane Adamson has already reported on one, in art-scot 3, and now she’s following the trail to in inform us on them all.

I am in Burlington House, Piccadilly, London, in the Royal Academy coffee shop, contemplating what I will have for lunch, but distracted from the salads, and looking over the tops of the wine glasses, I am drawn to the painted wall above.

Leonard Rosoman, detail from Burlington House Interior, Exterior

Many of you will know the colourful scenes on the wall I am describing: crowds in the Royal Academy courtyard; festive visitors in summer clothes flooding up its stairs to an exhibition; students painting a model. The life of the Royal Academy was captured on plaster by Leonard Rosoman OBE RA between 1985 and 1986.

Leonard Rosoman, Detail from Burlington House, Interior ,Exterior

‘Burlington House Interior Exterior’ is the title, the barely legible brass plaque tells me, a mural commissioned through ‘The EA Abbey Memorial Trust Fund for Mural painting in Great Britain’. How apt, as that’s why I was there.

Leonard Rosoman, Title plate from Burlington House Interior, Exterior

The Royal Academy looks after the Trust Fund records. The archivist, Mark Pomeroy, had kindly laid out a selection for me to inspect that morning on my second visit. A few months previously, I was on the trail of the Trust funding the Alberto Morrocco mural in St Columba’s Church, Glenrothes. A topic I wrote about in February 2023 in Issue 3 of art-scot. Then, I was only interested in the story behind that one mural, but on glimpsing through minutes with names like Sir Edwin Lutyens and Vanessa Bell on the committee, and noting there were other murals in Scotland, I was hooked. Where were they? Who were the artists? And, more importantly, do the murals still exist?

But I run ahead of my story as always. What was this Trust Fund?

The Edwin Austin Abbey Memorial Trust Fund for Mural Painting in Great Britain was set up in 1931 on the death of Mary Gertrude Abbey in memory of her husband, the American artist Edwin Austin Abbey (1852 -1911), an illustrator, painter, and muralist. His most famous set of murals are in the Boston Public Library. The Quest and Achievement of The Holy Grail took him 11 years to complete in his studio in England.

Edwin Austin Abbey with his wife Gertrude Mead, daughter of a wealthy New York merchant, lived in England and were very much part of the London establishment. Abbey was selected to paint the official scene of ‘The Coronation of King Edward VII’ when John Singer Sargent, the first choice of artist, and friend of Abbey’s, declined the task. This massive (2.75 x 4.5m) oil on canvas remains in the Royal Collection.

After her husband’s death, Gertrude was active in preserving her husband’s legacy, writing about his work and giving her substantial collection and archive to Yale University. The Trust Fund was part of that large legacy.

The trust funds (£80,000 and £2,000) were to be administered by the Trustees of the Royal Academy of Arts. Under the terms of the Deed:

“The selection of the Artists to be commissioned and the buildings to be decorated is left to the Committee”. In the margin, in pencil and underlined for emphasis, is the comment “this is definite”.

“Such a Committee is to consist of not more than 3 Members of The Royal Academy of Arts who are figures painters and architects nominated by and from amongst the President and Council of the Royal Academy”.

“There is also nothing to show whether the Artist selected is to have a free hand in determining the nature of the work he is to execute, or whether his subject is to be in any way prescribed. Presumably the subject will usually be chosen by the Owner of the selected Building and this in turn will effect the choice of Artist”.

“It is left to the discretion of the Committee to decide the method under which the selection of the Building and Artist shall be carried out”.

“Only those artists who have proven themselves draughtsmen, designers and mural painters of a very high order shall be entrusted with said commissions.”

This last sentence is pencil highlighted for emphasis.

The first meeting of the committee was held in 195 Piccadilly on 1st March 1938, with Sir Edwin Lutyens KCIE RA, Mr Henry Rushbury RA, and Mr F.V. Burridge OBE RE as Chairman and with Mr R. Blackmore in attendance. Sir Eric Maclagan CBE FSA, joined later. There is an interesting exchange in the minutes about the ‘Consideration of First Site’ for a mural. Sites such as the National Portrait Gallery, the Tate Gallery, St James Church, Piccadilly, and the Greek Church in Chelsea are amongst the names banded about and artists such as “Connard, Lawrence, John, Cameron and Duncan Grant”. Grand stuff indeed. Then the records go blank until 1948: World War Two intervened.

When the records resume it is with a notice that appears in The Times on 2nd April 1952.

Article from The London Times, 4th April, 1952 (Cutting courtesy: E.A. Abbey Memorial Trust Fund for Mural Painting in Great Britain, held by the Royal Academy, London.)

This brought a flurry of applications, including one from the Scottish Health Centre, Edinburgh. A project that failed to come to fruition.

It was six years later that the first mural in Scotland was successfully commissioned and executed.

In total over the period of 1961 to 1988, six Scottish murals were installed in public buildings, and these I list below as follows: site, artist, title, proposal and completion dates, size (very important as the artists were paid a rate per square foot), materials used, cost and the building’s architects. From the Royal Academy Edwin Austin Abbey Memorial Trust archives I have photographs of all the murals at the time they were completed, and where the murals still exist I have taken photographs of the same murals today.

Of the six: two are in the same location, one has been relocated, two have been demolished when building alterations took place, and the fate of one, at the time of this publication, is still being sought.

So, let’s start with the first commission. The dates in the text refer to entries in the Trust Fund’s minutes.

1. EDINBURGH UNIVERSITY STAFF CLUB, DINING ROOM, 9-15 CHAMBERS STREET, EDINBURGH

ARTIST: Leonard Rosoman OBE RA (1913–2012)

TITLE: Wheat, The Vine and The Olive.

PROPOSAL SUBMITTED: 10th July 1958.

DURATION: Work started 29th January 1959 and mural completed 20th January 1961.

SIZE: 11’ x 20’ = 220 sq ft.

MATERIAL: Oil paint on block board panels.

COST: £770 plus £100 for expenses and materials.

ARCHITECT: Basil Spence and Partners.

10th July 1958: “An application from the Secretary of the Edinburgh University was placed before the meeting in which it was explained the University had in progress the decoration and furnishing of premises to be used as a Staff Club and their Committee had approved a suggestion that a feature of the Club should be a mural painting by a well-known artist, a suggestion supported by the Professor of Fine Art in the University, Professor D. Talbot Rice, as well as the architect, Mr Basil Spence. The Club would be used for general functions such as banquets and receptions, the guests being other than Members of the University”.

The last sentence is important, for in the newspaper advertisement seeking applications to the Trust it states: “The proposed buildings should be such as are frequently visited by the public”. No murals were to be funded just for the elite.

10th July 1958 continues: “and if the proposal was carried into effect it was hoped to select a Scottish artist for the work”.

29th January 1959: Mr Dickey of the Committee had inspected and “it was agreed that a mural painting should be commissioned for the main wall of the dining-room… and for a similar wall in the Refectory. Mr Leonard Rosoman, who was familiar with the site should be entrusted with one of the murals… and that Professor D. Talbot Rice had received, after long negotiation, an intimation from John Maxwell of his willingness to paint a mural for the Club”.

3rd September 1959: Mrs Vanessa Bell felt obliged to resign from the Committee as “she found it too difficult to come to London when wanted” and Mr John Maxwell had to withdraw from the mural commission “owing to having developed angina.”

“Professor Talbot Rice had expressed the wish that Mr Leonard Rosoman should proceed with his design”, which he did.

And here is the sketch for the design, from the Trust archives.

Leonard Rosoman Wheat, The Vine And The Olive (Photograph courtesy: E.A. Abbey Memorial Trust Fund for Mural Painting in Great Britain, held by the Royal Academy, London. Photographer: Drummond Young, Edinburgh.)

Leonard Rosoman, of the Burlington House mural described above, was no stranger to Edinburgh. He moved there in 1948 to teach Mural Painting in Edinburgh College of Art. In 1954 he organised the Sergei Diaghilev exhibition at the Edinburgh Festival, where, with the help of his students, he made a large mural at the art college where the exhibition was held. These were heady days for mural painting.

In 1956 Rosoman moved to Chelsea School of Art and in 1957 to the Royal College of Art where David Hockney was one of his students. In 1960 he was elected an associate of the RA, becoming a full academician in 1969.

It was Professor D. Talbot Rice who wrote the letter of thanks to the Trust Fund on the mural’s completion.

The subject matter as outlined in the deed, would be chosen by the owner of the building, in other words, members of the university, guided by both Professor D. Talbot Rice and the architect, Basil Spence.

‘Wheat, The Vine and The Olive’? The reference I take to be from The Bible, Deuteronomy 8:8 “A land of wheat, and barley and vines, and fig trees, and pomegranates; a land of oil olive and honey”. Prefacing that is the verse “Therefore thou shalt keep the commandments of the Lord”, so that you will be in a land that never goes hungry – always food on the table. It’s a good subject for a university staff room dining room wall, the allusion being not only to food, but learning as well.

If it sounds oddly religious in 2023, it was painted over 60 years ago when church-going was the norm, Sunday was a day of rest, and Divinity a popular subject at Edinburgh University.

The subject of the mural is calm relaxation after a harvest. Characters sit lazily around a large central table, on which we see a basin of fruit, bottles of wine, and glasses; a vine trails idly over a cross-like structure, whilst a striped screen is being pulled by a figure in dungarees. Clothing is loose. Straw hats are worn. Someone has flopped in a deckchair. Dogs sprawl coolly shaded underneath the table. The mural breathes heat, and plenty. The colours purple, faded wine red, smudged black olive and wheat cropped fields. Tuscany meets East Lothian farmland. Edinburgh Staff Club is bathed in Mediterranean light.

But what was the purpose of the large striped screen to the left of the mural? That mystery was solved only the other day when the University of Edinburgh confirmed the mural had been removed in 2002. Photographs show it was painted in 5 panels, in colours richer and more vibrant than the sketch and the left hand panel had “a large rectangular hole in it to accommodate the serving hatch”. The striped screen disguised the serving hatch. Of course. What a playful piece of design.

The mural was destroyed in 2012.

Let’s move onto the second commission, also in Edinburgh.

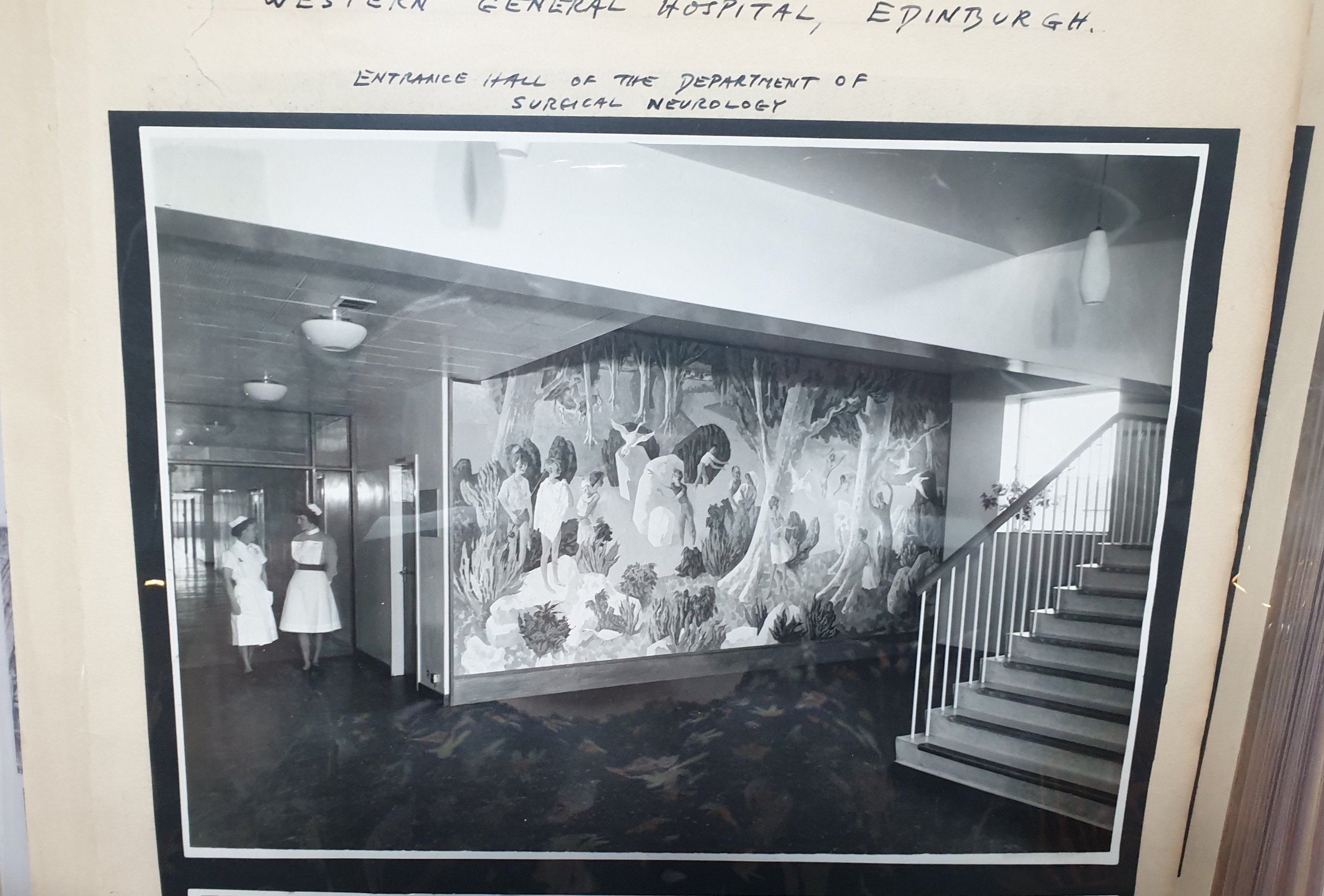

2. WESTERN GENERAL HOSPITAL, ENTRANCE HALL OF THE DEPARTMENT OF SURGICAL NEUROLOGY, EDINBURGH

ARTIST: Robert Lyon (1894–1978)

TITLE: ‘Pastoral’

PROPOSAL SUBMITTED: 1st July 1960

DURATION: Work started 6th October 1960, mural completed 30th April 1962, opening ceremony 12th May 1962

SIZE: 10’ 6” x 20 ‘ = 210 sq ft.

MATERIAL: Oil paint on board.

COST: £938.15. 0d and £176. 8. 4d for expenses and materials

ARCHITECT: John Holt, Southern Regional Hospital Board, Scotland

Robert Lyon, Pastoral (Photograph courtesy: E.A. Abbey Memorial Trust Fund for Mural Painting in Great Britain, held by the Royal Academy, London. Photograph: Photo Illustrations, 33 Cockburn Street, Edinburgh)

Of all the Trust archive photographs this is my favourite. Two occupants of the building, a staff nurse and junior, give scale to the piece and period setting. When did you last see a starched white apron springing from the clipped black waistband, except in a TV drama? And the floor, surely it must be linoleum, polished to a glisten, reflecting the serene woodland scene.

In searching for this mural, I went to the Western General Hospital. The building is still there but due for demolition. I investigated, but there was no sign of the mural. Perhaps it moved with the Department of Surgical Neurology, now called the Department of Clinical Neurosciences, to its new location at The Royal Infirmary on the eastern side of Edinburgh.

No, no mural there, that I could find. Instead, a very moving story about the man who developed neurosurgery in Scotland, Norman Dott (1897-1973). An Edinburgh man who attended George Heriot’s, Dott had chosen an engineering career until he got interested in medicine as a result of a lengthy period in the Royal Infirmary of Edinburgh’s orthopaedic ward after a serious motorcycle accident. At first his neurosurgery work had neither financial support nor hospital beds. He operated in a nursing home in the New Town of Edinburgh, until eventually he claimed a few beds and operating space in the Royal Infirmary and in 1938 he had the first dedicated neurosurgery department in Scotland.

Why dwell on this? Because that building due for demolition at the Western General Hospital was Dott’s dream. Opened in 1960, it combined neurosurgery, neurology and rehabilitation facilities under one roof. It was truly cutting-edge. Dott, at the age of 63, had achieved something remarkable. It was no surprise that he was made a Freeman of the City of Edinburgh.

I cannot believe, given Dott’s passion, that he would not have had a hand in choosing, if not the artist, then certainly he would have had a strong say in the subject matter: ‘Pastoral’. A rural ideal but given the context of the department and its care for its patients, emotional and spiritual support too. Seeing a photograph of this remarkable individual, stiff in his tweed suit (he never fully recovered from his motorcycle accident), I felt a little emotional too.

Now to the artist. The minutes record on 1st July 1960 that there was an application for two murals in the hospital. One in the Entrance Hall and the other in the Staff Lounge. The latter application was rapidly refused. Perhaps because it was not considered an area frequently visited by the public.

The Entrance Hall one proceeded.

7th July 1960: A mural by Mr Augustus John was considered for the site but “it would not fit” (the Trust seemed to have a John mural lurching about, but what that story is, I have no idea) and therefore decided to “invite Robert Lyon for a design”. Something designed for this site, this special department. Lyon duly proceeded.

Born in Liverpool, Lyon was three years older than Norman Dott: both men were in their 60s. Lyon had been Principal of Edinburgh College of Art from 1942 to 1960, so on the meeting date of 20th January 1961 when he was preparing the design, he was newly retired, and had moved.

The work, we learn from the minutes, is oil on board and Lyon is preparing it in his studio, not in Edinburgh, as the minutes record he “will be taking his mural to Edinburgh”. But from where? On 21st March 1962 there is an outing to view the finished work in Lyon’s studio, and given that three out of the five Trust Committee members go, plus the Secretary, I think his studio was in or near London.

By 30th April 1962 it was installed in the entrance of this life-changing building, which had taken almost 3 decades to come about. No wonder a dream-like scene was chosen as the subject matter: children bathing and playing; a couple central with a babe in arms; and swans (thought to symbolise grace, purity, gentleness) flying upwards out of this pastoral idyll. There is a fresh innocence about the work, a ‘hope for something better’, which it must have been for the many who entered its doors.

I can’t tell you what colours Lyon used. I only have the black and white photograph from the archive, taken just after the painting was installed.

This mural has not been found. Yet.

Let’s move on, optimistically, to the mural which started me off on this Edwin Austin Abbey Memorial Trust mural search. A mural that is still in its original position, and the largest of the six.

3. ST COLUMBA’S CHURCH, GLENROTHES, FIFE

ARTIST: Alberto Morrocco OBE FRSA FRSE RSW RP RGI LLD (1917-1998)

TITLE: ‘The Procession to Calvary’ aka ‘The Way of The Cross’

PROPOSAL SUBMITTED: 20th January 1961

DURATION: Work started September 1962, mural completed 11th February 1965

SIZE: 8’3” x 51’3” = 423 sq ft

MATERIAL: Painting direct on wall surface.

COST: £1,850 and £112.10.0 for travelling expenses.

ARCHITECT: Wheeler and Sproson

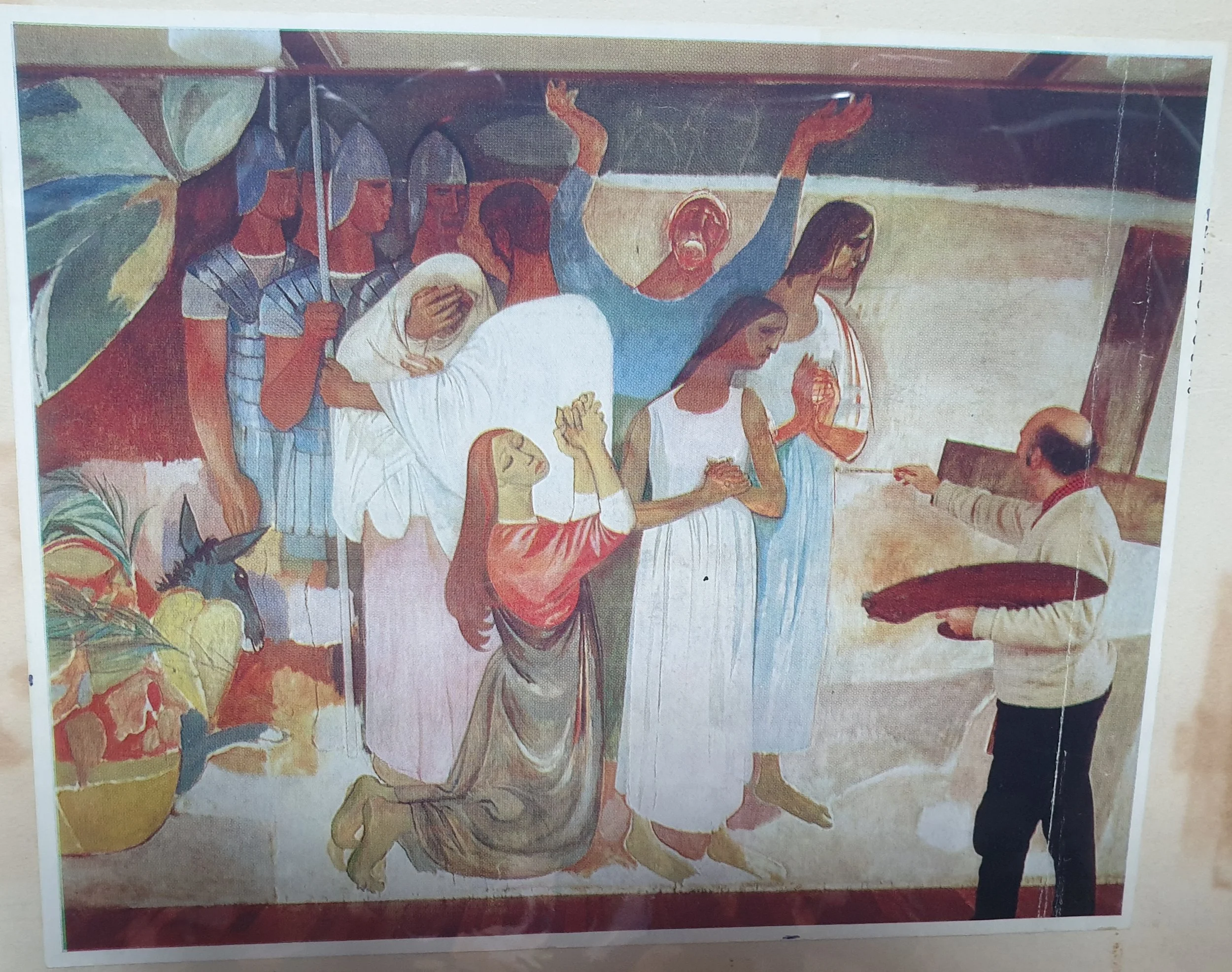

Alberto Morrocco The Procession To Calvary (Photograph courtesy: E.A. Abbey Memorial Trust Fund for Mural Painting in Great Britain, held by the Royal Academy, London. Photograph: Joseph McKenzie ARPS)

I have written at length about this in the February 2023 Issue 3 of art-scot, so will make this entry brief.

The first approach to the Trust was on 20th January 1961, when they received an “Application for painting a frieze mural on four sides of the church. Architects recommend mural on heavy beech veneered plywood, that subject be ‘History of the Church of Scotland’ and that Mr Alberto Morrocco ARSA be considered as the artist”. This was to be a mural for a new church in the New Town of Glenrothes, Fife.

The artist, son of Italian immigrants who had settled in Aberdeen, had trained at Gray’s School of Art in Aberdeen and was at the time Head of Painting at Duncan of Jordanstone College of Art in Dundee, a position he had held since 1950.

This was not the first time Alberto Morrocco’s name had been proposed for a mural. Six months previously in July 1960, the architects Thoms & Wilkie had applied for St John’s Roman Catholic Junior Secondary School in Dundee. The application was refused. “A picture by Mr Alberto Morrocco in the Royal Academy Summer exhibition was inspected but did not find favour”. Remember those terms of the deed? “The selection of the Artists to be commissioned and the buildings to be decorated is left to the Committee”. Here is an example of them doing just that.

What changed in those six months? Was it the persuasive powers of the architects? Anyway, Mr Anthony Minoprio from the Committee agreed to inspect St Columba’s Church “but notes that the building materials appeared to be of poor quality” and in June 1961 after his inspection “reports that wall at back of Chancel would be best site for mural”. Which is exactly what happened.

Alberto Morrocco The Procession To Calvary in situ, 2023.

If we look at the photograph above, you can clearly see where the architect intended the original mural to be painted. On the plywood panels, above and surrounding the congregation, in a central position, echoing one of the earliest post-reformation churches in Scotland at Burntisland. And the first church to have a square plan.

That also explains the coloured glass above, which would have flooded the mural panels with light. Poor quality building materials (the beech veneered plywood) meant the mural moved to the back of the church, with a design change too.

I think this decision, which must have been devastating to the architect at the time, was fortunate, for it spared us from having yet another “History of the Church of Scotland” soaring above our heads. Instead, there was a rethink and in its place is this magnificently larger than life portrayal of Christ on his last journey, providing an intimate backdrop for worship: Jesus in our midst.

Alberto Morrocco, Detail from The Procession To Calvary

Morrocco provided two designs for this wall, given he had already given one design for the original site he must have been praying for third time lucky, and happily it turned out to be so. In September 1962, his second design was approved by the church and he commenced work.

Remember the terms of the deed: “the subject will usually be chosen by the Owner of the selected building”, so the church has chosen the subject.

Alberto Morrocco painting The Procession To Calvary (Photograph courtesy: E.A. Abbey Memorial Trust Fund for Mural Painting in Great Britain, held by the Royal Academy, London).

17th October 1963 records “Morrocco at work and submitted photographs”. This is probably the date of the above photograph in the archives. Some congregation members of St Columba’s Church remember watching him at work, and how proud they were. Rightly so. It is a much-loved piece.

By 3rd November 1964, he was virtually finished. He was paid the balance of his fee and his expenses were reimbursed, at 6% of his fee: a sizable amount. There was all of that driving from Dundee to Glenrothes via Perth, pre-Tay Road Bridge - a long journey - which also helps explain why this in-situ mural took so long to complete: over two years.

St. Columba’s Church became a Category A Listed building in 2004:

“An influential and liturgically-experimental centrally designed church which took its model from Burntisland Parish Church. Listed for its contribution to ecclesiological change, the quality of its stained glass and mural”.

There you go, Morrocco’s mural vindicated!

One last note: it was originally called ‘The Procession to Calvary’. That’s how it is labelled in the archives, but at some point, there was a name change to ‘The Way of the Cross’.

That was not the only name change. The Trustees at the beginning of the 1970s start to administer two funds and their letterhead became:

THE EDWIN AUSTIN ABBEY MEMORIAL TRUST FUND FOR MURAL PAINTING IN GREAT BRITAIN

THE E. VINCENT HARRIS FUND FOR MURAL DECORATION

The two trusts do not concern us here, as none of the next three murals were paid for out of this new pot.

However, given the Committee were now running two funds for mural painting, they chose at this point to list the murals which had been commissioned under The Edwin Austin Abbey Memorial Trust Fund for Mural Painting in Great Britain. There were 31 in total, and 3 of these were in Scotland.

I have attached this list in Appendix A at the end of this article.

It is outside the scope of this article to discuss or even tackle the other commissions, but it would make for an interesting area of study.

Moving forward, we jump a few years, to St Andrews this time and another Dundee artist.

4. UNIVERSITY OF ST ANDREWS, STUDENT UNION, ST ANDREWS, FIFE

ARTIST: David McClure RSA RSW

TITLE: ‘Earthly Paradise’

PROPOSAL SUBMITTED: 5th December 1972

DURATION: Work started 6th February 1974, mural completed 14th July 1975.

SIZE: 6’ 8” x 24’ 6” = 165 sq ft.

MATERIAL: Paint on plaster wall.

COST: £1,200 and £100 expenses.

ARCHITECT: H. Anthony Wheeler of Wheeler and Sproson

The first application in December 1972 from the architects, Wheeler and Sproson (those self-same architects of St Columba’s Church, Glenrothes above), was for a mural at the top of the staircase on the second floor. The building was still incomplete. Completion was expected in early March 1973.

The records then leap.

On 6th February 1974 the Committee are asked to “inspect and vote for or against a sketch design by Mr David McClure RSA for the mural painting to be commissioned for the north wall of the dining room on the second floor of the new Student’s Union of the University of St Andrews (Architects: Wheeler and Sproson). It has been accepted by the university”.

13th March 1974: the sketch design by David McClure is approved. The Student’s Union Dining Room Wall it is. This is the second dining room wall in a Scottish University to have an E.A. Abbey Trust funded mural; the first was the Staff Dining Room in Edinburgh.

By July 1975 the mural was complete – from start to finish in just over a year.

David McClure, Earthly Paradise (Photograph courtesy: E.A. Abbey Memorial Trust Fund for Mural Painting in Great Britain, held by the Royal Academy, London. Photograph: Mr Harvey of Leven.)

How can you not be captivated by Mr Harvey of Leven’s mid-1970s photograph? Tan banquette seating lining the wall with down lights dangling through the ceiling tiles (don’t miss those fire hazards one bit), I almost want to be there, without the loon jeans, of course.

I have to be captivated, as this is the only photograph I have of the mural in situ. On enquiring about the mural, in early July, the University of St Andrews came back very promptly.

Firstly, with details of the oil painting sketch for the mural, which they have in their University of St Andrews Libraries and Museums collection. I attach a link here: Sketch for Mural, Student's Union, University of St Andrews | Collections | University of St Andrews (st-andrews.ac.uk)

However, a second separate email from the university brought a different tale.

“Bad news regarding the mural formerly present in the Student’s Union…the mural wasn’t removed before the building was handed over to Morrisons Construction during our redevelopment and must have been destroyed when the walls were removed…I’m very sorry to be the bearer of bad tidings”.

These things happen. Things go missing, things get destroyed, some things survive: more than we realise. Memories for a start, so I am consoled that for over 40 years students ate, drank and partied with that McClure scene behind them.

David McClure was born in Lochwinnoch, and graduated from Edinburgh College of Art in the early 1950s, where he must have encountered the two artists already considered, Leonard Rosoman, who taught mural painting, and Robert Lyon who was Principal, plus the two artists I comment on next, Robin Philipson and James Cumming, who both lectured there at the time.

My point? There is a lot of overlap and exchange within these five Edinburgh College of Art artists. McClure taught for a spell at Edinburgh College of Art however the bulk of his life was spent further north in Dundee. From 1958, he taught at Duncan of Jordanstone College of Art, taking over in his last two years as Head of Painting in 1983 to 1985 from his friend and colleague Alberto Morrocco.

McClure’s experience for the project? Whilst teaching in Edinburgh, in the 1950s, McClure painted murals and ceilings in the reconstruction of the King’s Room at Falkland Palace, Fife. The work can still be seen today.

McClure’s subject for the dining room wall was “Earthly Paradise”. He conjures it up as warm, given the scant clothing everyone is wearing. The central man astride the bridle- and saddle-less horse looks out at us, dog attentive at his side, around them are white lilies, birds and horned animals. Adam and Eve characters are entwined to the right by the tree.

What was his inspiration? The figures on the extreme left and right look like they’ve escaped from a Gauguin ‘paradise’. Perhaps he also drew from ‘Earth (The Earthly Paradise)’ by Jan Brueghel, the Elder (1607-1608), which would explain those horned animals, or Pierre Bonnard’s ‘Earthly Paradise’ (1916 -1920) with its Adam and Eve.

I only have access to site photographs, but composition-wise, this painting is similar to the one by Robert Lyon for the Western General Hospital. Given the small scale of Scottish art circles at the time, McClure would surely have known of the other three murals that preceded him.

And colours? Earthy. It was the 1970s.

Onto Dundee next and another Edinburgh College of Art artist, Sir Robin Philipson.

5. DUNDEE COLLEGE OF EDUCATION, DUNDEE (IN LIBRARY, NEAR TO LIBRARIAN’S OFFICE)

ARTIST: Sir Robin Philipson RA PPRSA FRSE RSW (1916 – 1992)

TITLE: ‘High Summer’

PROPOSAL SUBMITTED: 24th September 1974

DURATION: Work started 27th September 1977.

SIZE: 14’ x 11’6” = 161 sq ft.

MATERIAL: Oil paint on board.

COST: £1,800

ARCHITECT: Thoms & Wilkie

The first application was on 24th September 1974. “Application for mural painting(s) in new building for completion, Autumn 1974. (Architects: Thoms & Wilkie). Drawings available; five sites suggested. Inspection required.”

Thoms & Wilkie had applied before, if you will recall in 1960, for their St John Roman Catholic Junior School in Dundee, and were refused. Undaunted, here they are again, fourteen years later, with a new application.

In July 1975, the painter, Frederick Brill, and the Secretary of the Trust inspected the building, recommending the site in the Library. Robin Philipson was suggested as the artist. Everyone was playing safe with their artist choices. Robin Philipson had been appointed President of the Royal Scottish Academy two years before. He was duly invited to submit a sketch design for a wall in the library by the Librarian’s Office and in November 1975, Philipson agreed.

By March 1976, approval of his sketch design was given, and while hoping to complete in early 1977, he was more or less on target, for by 1st September 1977 the mural was awaiting installation.

Robin Philipson, High Summer, in situ, 2023.

The mural still exists. Here it is, but not in the original building it was planned for. Dundee College of Education was demolished at the end of 2009, and the mural was moved to the Queen Mother Building, University of Dundee, Small’s Wynd, in the area Dundee Council calls the University Conservation Area. The mural hangs high in the area they call ‘The Street’. Anyone can go to view it and I suggest you do. It’s a cracking painting. Marginally it is the smallest of all the six murals, but hopefully my photo gives some sense of its scale.

HIgh Summer in original location, Dundee University Library, courtesy Matthew Jarron, University of Dundee Museums

Here is a photograph of the mural in its original position by the library, and I found an online article by Mark Chalmers written in 2018, which gives a flavour of the building and its atmosphere. He heads his piece ‘Dundee’s Burrell: Thoms & Wilkie’s Swansong’.

I quote from his article in relation to the library, at the start of the 2000s:

“Like the building fabric, the interior fit-out was also perfectly preserved from the late Seventies, with the original fawn-coloured needle-punch carpet, sage green moulded plastic chairs, and timber study cartels.

It was a sanctuary, and the glazed gallery around the edge of the library was reminiscent of both Jim Stirling’s work at St Andrews, Leicester and Cambridge; and the later Burrell Gallery in Glasgow was even closer in execution…

On a weekday afternoon you could sit on the bright edge of the library and flick through books from the 1970s that had long disappeared from other libraries…I got into Saul Bellow and Lawrence Durrell, and rediscovered Joseph Heller, thanks to the original librarian’s catholic tastes”

What did the librarian make of this magisterial mural next to his office? I suspect he would think Philipson would find Bellow, Durrell and Heller good company.

Robin Philipson, Detail from High Summer

‘High Summer’ sings yellow. Philipson’s signature fighting cocks are in the bottom left hand corner; models draped over frames to be painted; zebras shadowy behind, with Spanish style bulls; a greyhound running furiously off the canvas below.

It was hung lower down in its original position. I like a face to face encounter with a mural: tempting you to touch it.

For the last mural, you can do just that: touch it. Much to the consternation of its new custodians. It sits at floor height. For this commission I head to Linlithgow, as far west as the commissions go. The artist was by the recently retired Edinburgh College of Art lecturer, originally from Dunfermline, James Cumming.

6. LOW PORT COMMUNITY CENTRE, LINLITHGOW, WEST LOTHIAN

ARTIST: James Cumming RSA (1922 – 1991)

TITLE: ‘The Community; A Festival of Time’

PROPOSAL SUBMITTED: 1st June 1987

DURATION: Work started 27th January 1988, mural completed 20th July 1988.

SIZE: 17’ x 20’ 8” = 350 sq ft.

MATERIAL: Painting directly on wall surface.

COST: £5,012

ARCHITECT: H. Anthony Wheeler of Wheeler and Sproson

James Cumming, The Community, A Festival Of Time, in situ 2023

Last, but by no means least. Here it is in position, on the landing, midway up the main staircase. Looking as crisp as when it was first painted.

A whole article could easily be written about this mural, and indeed many articles have been, especially as there is also the uplifting tale of how it has been saved.

I had read that St John’s Church, Linlithgow, was hoping to take over the empty Low Port Community Centre, the site of the mural. I wrote to St John’s and an email came in from Heather Begarnie of the church:

“Thank you for getting in touch. We expect to get the keys to the Low Port Centre on 1 September. The mural is still in the building and Historic Environment Scotland are assessing it with regard to it being listed. We can arrange an ad hoc visit if you would like to view the mural.”

Would I like to view the mural? Of course. I rang her back immediately and drove over to see it that afternoon. Always good to end a Friday on a high note, and this was one of those.

In late 2021 Low Port Community Centre was up for sale by West Lothian Council and the mural was under threat. Local action galvanised many in Linlithgow to save the mural, culminating in Local Constituency MSP for Linlithgow, Fiona Hyslop, adding her support to the artist’s daughter, Laura Cumming, Chief Art Critic of The Observer, in wishing to save James Cumming’s final masterpiece. On 28th December 2021, she wrote on her Constituency website:

“I am very concerned that by selling off the Low Port Centre in Linlithgow, West Lothian Council are in danger losing the important James Cumming mural painted behind the main staircase in the building which is quite unique, reflects the spirit of Linlithgow, and is irreplaceable.

The artwork is recognised in Linlithgow and beyond by locals, visitors and other members of the art community. The mural is symbolic of the nature and characteristic of community and spans across generations.

I have written to both Historic Environment Scotland and Creative Scotland urgently for their support in retaining this important piece of art, history and heritage for the local people and future generations to enjoy”.

The electrician who let me into the building commented “Aye, there’s a whole lot of history in Linlithgow”. I looked at him quizzically. “I’ve worked around the town for decades, and there’s aye ways something to learn”.

Always something to learn. Too right.

This mural is a complex piece so ‘The Community: A Festival of Time’ has an accompanying chart to explain the characters within the story – thirty nine in all.

The Community: A Festival of Time

James Cumming, Detail from The Community, A Festival In Time, Character 38 ‘The Media’ and dog.

But how did it all come about?

The first mention in the Trust’s minutes is:

9th June 1987, when the building was called Linlithgow Community and Outdoor Education Centre: “Prof. Dannart (of the Committee), to consult the architect, H. Anthony Wheeler, and, subject to satisfactory outcome and approval of a scale drawing of the wall in relation to the half-landing, invite James Cumming to submit a sketch design”.

20th January 1988: “Artist, James Cumming, is now preparing sketch designs and a Certificate signed by Lothian Regional Council Education Authority has been received”.

20th July 1988: The building is now called Low Port Community Centre, Linlithgow. “The Secretary reported that the commission at Linlithgow by James Cumming now complete. Following a query by the artist, the inscription on the work, required under the terms of the fund, was agreed”.

That’s it: three entries in the records - sketch to finish in six months. Is it the fastest commission executed? Certainly, the fastest Scottish mural. Cumming must have gone to it with a will.

Sandy Wood of the RSA (note 1) explained: “Cumming lived at the Centre during the week and was to become a favourite with the people there, many of whom still remember his colourful wit and personality. He took the idea of developing a community mural seriously, and was clear that it should be something that everybody could connect with and appreciate, no matter what their understanding of art.”

In 1990 the mural was given the Saltire Society Award. Cumming died the following year.

James Cumming, Detail from The Community, A Festival In Time: Character 3 ‘Ancient Monuments’ and Character 33 ‘Nursing’

Cumming lectured at Edinburgh College of Art from 1950 to 1982, teaching in both Humanities and Painting, and had amongst his students Alexander (Sandy) Moffat and John Bellany.

On 6th February 2020, I attended a talk in Perth Museum and Galleries given by Moffat on the John Bellany paintings which were on display in the gallery.

On that day I wrote in my diary:

“Sandy Moffat’s talk on John Bellany enlightening. A firsthand account of his friend and fellow student at Edinburgh Art College. He spoke to the paintings. Done as student works. First, the large boat building mural (‘The Boat Builders’ 1962). Their tutor, James Cumming, had been teaching them about the Mexican tradition of murals in the 1930s and Diego Rivera.”

Moffat mentioned it was worth seeing James Cumming’s Linlithgow mural. For three years it has been at the back of my mind to find it. And now I have.

What have I learned?

We have much to thank Edwin Austin and Mary Gertrude Abbey for.

The successful applications cluster around themes, artists, and places: Edinburgh and Dundee recur.

All six artists were teachers: four of the artists taught at Edinburgh College of Art (and a fifth for a short spell) and two taught at Duncan of Jordanstone in Dundee. All the murals are in the East of Scotland. It was always down to architects to commission and Kirkcaldy based Wheeler and Sproson, who applied and were successful in three instances, championed murals in their buildings.

The locations were three places of education, one hospital, one church and one community centre. Interestingly, it is only the latter two that have their murals still in their original location.

All six murals feature warmth, often summer, and optimism, for even ‘The Way of the Cross’ has hope.

As I type this in late-July, I am optimistic too, perhaps I will find that last Edinburgh mural.

Note 1. From an article by Sandy Wood in The Black Bitch, August 2016, p.6

My thanks to:

The Royal Academy for giving access to The Edwin Austin Abbey Memorial Trust Fund for Mural Painting in Great Britain records and photographs, and to the archivist Mark Pomeroy.

The Minister of St Columba’s Church, Glenrothes, Rev. Alan Kimmitt, who started me off on this trail.

The University of St Andrews staff and Dr Gearoid Mac a’ Ghobhainn, Collections Curator for showing me the David McClure sketch.

The University of Edinburgh staff, in particular Claire Walsh and Liv Laumenach who helped me confirm the fate of the Edinburgh University mural.

Matthew Jarron, Curator Museum Services, University of Dundee.

Heather Begarnie, Community Development Manager, St John’s Church, Linlithgow.

LOCATIONS OF EXISTING MURALS (3)

St. Columba’s Church, Rothes Road, Glenrothes, Fife KY6 1BN

Queen Mother Building, University of Dundee, Small’s Wynd, Dundee DD1 4HN

Low Port Centre, Blackness Road, Linlithgow EH49 7HZ

DEMOLISHED MURALS (2)

Edinburgh University Staff Club, Dining Room, 9-15 Chambers Street, Edinburgh EH1 1HT

University of St. Andrews, Student Union, St Mary’s Place, St Andrews KY16 9UZ

MURALS NOT FOUND YET (1)

Ex-Western General Hospital, Entrance Hall, Department of Surgical Neurology, Edinburgh EH4 2XU

APPLICATIONS FOR MURAL COMMISSIONS THAT FAILED TO COME TO FRUITION (7)

1955 Edinburgh Scottish Health Centre

1960 Edinburgh University: Salisbury Green Halls of Residence

Architect: WH Kininmonth

Location: Senior Common Room and Junior Common Room

1960 Edinburgh University: Engineering Extension, Kings Buildings, Mayfield Road

Architects: Stephenson Young and partners, Edinburgh

Location: Entrance Hall

Artists considered Ian GM Eadie and Anne Redpath “if she has any experience in mural work”

1960 Dundee: St John’s RC JS School

Architects: Thoms & Wilkie, Dundee

Location: Dining Room

Artist: Alberto Morrocco

1966 Edinburgh University: Department of Molecular Biology

Architect: Kingham Knight Associates

Location: 2 sites in Entrance Hall on the 6th Floor

1975 Livingston: West Lothian Sports Hall

Artist and work: ‘Climbing Wall’ by Mr. George Garson to be executed in 1977-78

1977 Edinburgh: Royal Lyceum Theatre

Application for various mural paintings: sketch design for one of them by John Byrne

APPENDIX A

WORKS COMMISSIONED THROUGH THE EDWIN AUSTIN ABBEY MEMORIAL TRUST FOR MURAL PAINTING IN GREAT BRITAIN (1950 – 1971)

Marked in bold type are the Scottish Commissions

1. WHITECHAPEL ART GALLERY, LONDON, E1

“The Seasons” by John Napper, 1950-51 (240 sq ft)

2. BRISTOL COUNCIL HOUSE

Conference Room Ceiling by WT Monnington RA, 1953-56 (3,200 sq ft)

Council Chamber Ceiling by John Armstrong, 1953-55 (3,600 sq ft)

3. UNIVERSITY OF LONDON UNION, LONDON, WC1

“The Scholar Gipsy” by Gilbert Spencer ARA, 1955-56 (155 sq ft)

“Charivari” by Clive Gardiner, 1955 (125 sq ft)

4. LINCOLN CATHEDRAL

Walls of the Russell Chantry by Duncan Grant, 1955-59 (360 sq ft)

“The Good Shepherd ministers to His Flock”, “Sheep-shearing”,

“The Wool Staple in medieval Lincoln” and “St Blaize”.

5. ST PHILIP’S CHURCH, HOVE

“All ye works of the Lord, Bless ye the Lord, Praise Him and magnify Him forever” by Augustus Lunn, 1957-58 (273 sq ft)

(One-third of the cost paid by the church)

6. UNIVERSITY OF EDINBURGH STAFF CLUB

“Wheat, the Vine and the Olive” by Leonard Rosoman ARA, 1960 (220 sq ft)

7. EVILINA CHILDREN’S HOSPITAL, LONDON, SE1

“Pearly King and Queen” by Betty Swanwick, 1960 (57 sq ft)

8. QUEEN ELIZABETH COLLEGE, LONDON W8

“Nutrition” and “Biology” by John Brine, 1961 (111 sq ft)

9. WESTERN GENERAL HOSPITAL, EDINBURGH

“Pastoral” by Robert Lyon, 1962 (210 sq ft)

10. ST MICHAEL AND ALL ANGELS’ CHURCH, LONDON E8

Eight wall paintings by John Hayward, 1962 (960 sq ft)

11. ST FRANCIS CHURCH, LUTON

“To the end of time” by Mary Adshead, 1962 (600 sq ft)

12. ROYAL MARSDEN HOSPITAL, SUTTON

“The Park” by John Armstrong, 1962 (544 sq ft)

13. ST PHILIP’S CHURCH, LONDON, SE1

“The Angelic Hierarchies” and “The Cruxification”

By John Hayward, 1963 (656 sq ft)

14. SHEFFIELD TEACHING HOSPITAL

“Whitby” and “Chatsworth” by Richard Eurich RA, 1963 (238 sq ft)

15. NEWPORT, MON., CIVIC CENTRE

Wall paintings in Central Hall of “The History of Newport”

By Hans Feibusch, 1961-64 (3,000 sq ft)

(Half the cost paid by Newport).

16. MANCHESTER CATHEDRAL

“The Sermon on the Mount and the Beatitudes” and “The

Transfiguration” by Carel Weight ARA, 1963 (40 + sq ft)

17. WOODFORD GREEN UNITED FREE CHURCH

“God in Creation” by Jean Clark, 1963 (405 sq ft)

18. ST. ANDREW’S LUTHERAN CHURCH, RUISLIP

“St Andrew, Fisher of Men” by Norma Blamey, 1964 (77 sq ft)

19. UNIVERSITY OF LONDON UNION, LONDON, WC1

Two abstract paintings by WT Monnington RA, 1964 (192 sq ft)

20. UNIVERSITY OF HULL, PHYSICS BUILDING

“Atomic Bodies”, “Heavenly Bodies”, “Interference Patterns”

and “Radiations” by Edward Bawden RA, 1964 (478 sq ft)

21. ST COLUMBA’S CHURCH, GLENROTHES

“The Procession to Calvary” by Alberto Morrocco ARSA

1963 -64 (423 sq ft)

22. YVONNE ARNAULD THEATRE, GUILDFORD

Fired metal screen in Foyer by Stefan Knapp, 1965 (200 sq ft)

23. BIRMINGHAM DENTAL HOSPITAL

“Fair-ground Scene” by AR Thompson RA, 1965 (294 sq ft)

24. CHURCH OF CORPUS CHRISTI, WESTON-SUPER-MARE

“Christ in Majesty”, “St Mary Magdalen” and “St Peter”

by Jean Clark, 1966 (108 sq ft)

25. UNIVERSITY OF MANCESTER INSTITUTE OF SCIENCE & TECHNOLOGY

“Metamorphosis” by Victor Pasmore CBE, 1968 (770 sq ft)

26. KING’S COLLEGE HOSPITAL DENTAL DEPARTMENT, LONDON, SE5

“At the Seaside” by Robert Lyon, 1968 (160 sq ft)

27. LONDON GRADUATE SCHOOL OF BUSINESS STUDIES, LONDON, NW1

“The Lovely Vision of Regent’s Park” by Leonard Rosoman RA, 1970 (288 sq ft)

28. ST MARY’S CHURCH, CHESHAM, BUCKINGHANSHIRE

“Holy Week” by John Ward RA, 1970 (384 sq ft)

29. CARRS LANE CHURCH, BIRMINGHAM

Three Roundels by Edward Bawden CBE RA, 1971 (144 sq ft)

30. ST HELIER HOSPITAL MEDICAL CENTRE, CARSHALTON, SURREY

“Lysistrata” by Arthur Boyd, 1971 (280 sq ft)

31. INTERNATIONAL STUDENTS TRUST, LONDON, NW1

“Summer Eclogue” by Roger de Grey RA, 1971 (176 sq ft)