Jane Hunter: Out of the Blue

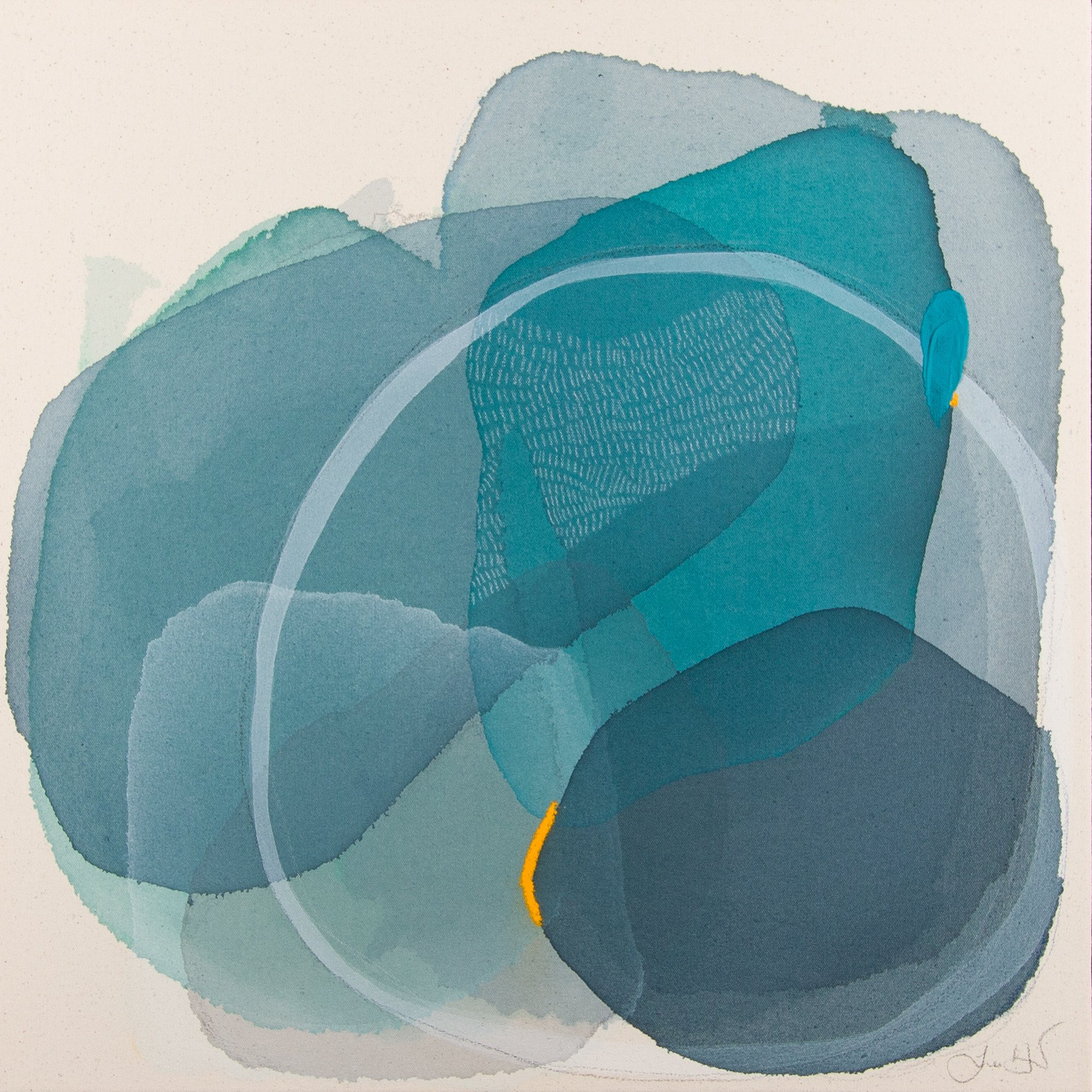

Jane Hunter is settled in her airy flat high up above Rothesay’s rooftops. From her kitchen window, she can pretty much see the whole of the town, but crucially she has a wider view of the world. The hill on her horizon, which she calls her muse, is also a constant reminder “that there’s all this wide open space beyond.”

Jane Hunter, Belonging, 2023

She moved to Bute in December 2022, and it already “feels more like home than anywhere else I’ve lived”. I wonder why. “I think the word that keeps coming up is proximity. Proximity to amenities, to workspace, which is different to living in a big town, and in a practical way makes things easier, but more importantly, the proximity to nature, the sea, and the small community that I’ve become part of, galvanizes my connections to all of these things, and makes me feel more part of them.”

Despite spending all of her life to date living in Renfrew and Paisley, she has a sense of belonging to her new island home. “A lot of that has been to do with people and that’s been luck. Meeting the right people when I first got here made me feel so comfortable, accepted and at home. These are people that completely get who I am, and got me really quickly, which I never felt really before in my life. I feel that I’m learning from them, and we’re sharing knowledge and feelings and all those aspects of life that really make you feel part of somewhere.”

Jane Hunter, Seeking, 2023

Chance and choice are constant companions in Jane’s life and art. She had never been to Bute before she and her partner travelled to the island to view property for sale. She had no family or friends there. Visiting her less than six months later, her home feels like a choice, a place that reflects her neat and ordered character, satisfies a longing for settlement and belonging, and, just over the hill, offers all the wonders of nature that provide creative inspiration and emotional anchor.

Her home is where her art is right now too. It is her paintings hanging on and leaning against the fresh white walls in her living room, her notebooks, sketchbooks and current reading neatly piled on the kitchen table, and her spare room meticulously organised into a studio where each tool has its dedicated place.

After the move, she didn’t paint for three months. Creating an ordered space to work in – physically and emotionally – took priority. Now she’s preparing for a solo exhibition, which she’s called “Confluence“ and which will be at Tighnabruaich Gallery from 12th August to 3rd September, 2023.

Her paintings are abstract inasmuch as they eschew the tangible, but for Jane, they’re representative. The subjects are nature and feelings. Prior to painting being her main focus, Jane worked in textiles and developed techniques that recreated and re-presented two dimensional maps in coloured textures.

Jane Hunter, Shelter Of The Kyles, 2018

Is her subject matter still the same? “That’s what I’ve always held on to.” she says, “No matter what I was making, whether it was maps of a very specific place, geological diagrams of a certain rock feature, or communicating my experience of being in a landscape, belonging, the sea… it’s all about communicating deeper meaning of place to an audience. The geology and topography was about showing people landscape and the world from a different perspective, so that they could get to know it at a different level, and I think that that same strain, that same thread, is what links all of my work together. I want to help people find connections, form relationships and begin conversations about how we live side by side with and care about the natural world we are part of. That’s my intention anyway.”

Jane Hunter, Kyles of Bute, Sheared, 2018

Nature is at the heart of her colour choices: both physical and human nature. “It’s double stranded in terms of colours. There are definitely literal representations of water, blue sky, blue water, green plants, lichen, mosses; yellows that come up in gorse, or there’s a yellow line on the ramp at the ferry, things like that that come up a lot. White marks come up a lot too, because the movement of water often shows up as a white mark. Equally important, if not more so, is the emotional representation of colour. For me, blue means so many things. I’ve read a book recently, ‘A Field Guide To Getting Lost’ by Rebecca Solnit, that’s nailed the colour blue for me, where blue is the colour of longing and of destiny. The world is blue at its edges, it’s where there is depth; blue is the light that got lost, the colour of solitude and desire, of here seen from there… and that sparked a lot of thoughts for me about feelings of belonging. It’s not that I’m trying to justify this colour palette that I’m stuck in, but in a way I suppose I do, because I can’t shake it. Why am I so drawn to this? I can see every colour under the sun in the landscape, of course. I’m not drawn to using them to represent anything that I’m feeling. These cooler blues, all the different tones and hues of blue… I’m sure there’s people who know more about this than me, but I’m sure that everyone’s emotional make up has a colour palette.”

Jane Hunter, The Ebb And Flow, 2022

We might see Jane Hunter’s paintings as the emotional maps of a creative person becoming more and more attuned to nature, where colours produce feelings and feelings produce colours, and the way in which those colours overlap create primary, secondary, tertiary (and further fractional) points of interest, and with the artist’s guiding hand offer suggestions as to how we might read the picture and recognise the feelings.

She’s been in this mode – painting, that is – for around four years now, and it’s clear to see the development in conception, composition, and control.

Jane Hunter, Just To Be, Here, 2019

“My art practice is my job, it’s what pays the bills. I chose to change, drastically in my mind, the materials and type of work I was making, which was a risk. So, rather than going through all of these stages of development and then presenting the outcome, I let people see and be part of the process I was going through. It does seem that it’s changed quite a lot in quite a short space of time, and that’s true, but that was me working it out, trying different things and learning, but just in a public way.”

Jane Hunter, Remnants of Passage, 2022

To my mind, the recent paintings have much closer management. What you might call order and neatness. Edges are less ragged. The paint only occasionally touches the edge of the canvas. The shapes are complete in the picture. Many feature holding lines, sometimes meandering, sometimes strong white lines that underline, give counterpoint, or wrap around her varied shapes. I wonder whether these fix floating ideas. Is she mapping and then embracing her emotions – some tied together, some loose? Is that shape safety, and the overlapping one ease? and is that settlement, and this a sense of wonder? And they’re all brought together into one entity, anchored for a moment, rather than left floating?

Jane writes a lot of notes, analysing feelings and creative processes. She turns the pages of her notebook and shares a recent musing: “Overall the notion is that these abstract paintings, their layers, colours, shapes, marks, are essentially maps. Maps of observation and experience, in the way that a topographical or geological map is an image of features and information, alongside some assumptions and artistic licences (because all maps do have an element of artistic licence, especially geological ones).”

Chance is important to Jane’s thinking, and she feels it’s a key component in her creative process.

However, it doesn’t extend to colour. Her palette is considered, tried and tested before she commences a period of painting, each colour diluted and mixed in cups ready to be utilised. But when she starts, she feels there’s chance at play in the marks she makes. Because she’s been working in the same way for some while now, the chance is tempered by experience. She knows what works best, but then again she wants to challenge herself.

Jane Hunter, A Symbiotic Dance, 2022

Jane has made attempts to design in advance, but they weren’t satisfactory. She has composition and a sense of what makes a successful painting in her mind throughout the picture’s progress and likes the intellectual challenge of responding to the image as it develops. In the case of acrylic on canvas, each mark takes a day to dry. Occasionally she’ll work wet on wet, but most of the time, she’ll wait for the pigment to dry so that she can see the extent of the stain, its form, and how it reacts with existing marks. It almost goes without saying that her dilutions are spread like watercolours, using gravity and tipping, in combination with brushes carrying varied loads, or no load as they shimmy the flood into shape.

How much chance and how much order is there?

Her canvasses can have 25 to 30 layers. One layer per day means it’s taken 25 to 30 days to complete. “With each layer comes more control”, she says. It’s in her notebooks and sketchbooks where the planning and design evolves, where the state of play is evaluated and ideas tested. She’ll use her diluted acrylic paint, body paint, pastels, and collage to work through options and consider potential whilst paint dries on canvasses.

So, Jane’s forms emerge through sequences of rapid action and long periods of contemplation. They are studied, but founded on feeling rather than design and calculation. Their organic nature gives them greater strength, I think. They feel as though they’ve grown naturally. They feel sturdy and enduring even though they retain their sense of transience, evanescence. They are floating clouds of emotional power as well as colour.

And there are always multiple canvasses being worked on at the same time – at least four in a series. “They feed into each other. If I do something that’s successful on one, I can repeat it on another, and if I find myself saying ‘Why did I do what I did on this one?’ I can sort it out on the others. If you’ve got all of them in front of you, you’re working on them as a whole.”

Concentration must be difficult over such a long period. The notes and the sketches have huge value in bringing her back to where she was when the last mark was made, but she also uses audio aids – audio books and sounds – to plug in to the appropriate emotional mood.

“What I’ve learned is how to manage time. I make a lot of notes. I know that I can’t dedicate all my time to the studio. I’ve had to learn how to stop and start, tap into thoughts and emotions when I need to.”

Jane Hunter, A Sea Of Memories, 2023

She uses the same techniques working in watercolours on paper, but with each layer drying after two hours, the decision making is much faster, moving towards improvisation. Freshness and experiment are to the fore, and the results have more fragility, more atmosphere, and more watery freedom as pigment settles into its own natural patterns.

There’s an extra element she applies to her works on paper. “Sometimes I attach all the paper to the same support, so that they’re all affected by the same action. If they’re all interconnected it forces chance on to pictures.”

It’s a more instant version of the same compositional craft that Jane is honing in her works on canvas. She knows what makes a successful painting, and one of the elements of this, she says, is that “I want the painting that I’m making to be pleasing to look at”. What pleases her? “Balance, I suppose. Balance of tone, and of composition. I guess going back to the mapping thing, how your eye reads the map of the painting, how you’re guided through the elements of the image.”

A Sea Of Memories, a brand new work, shows that she can achieve her objectives now in simpler forms, with great confidence and freer handling. She doesn’t want to lose the freshness of the core harmonies, the single colour strokes on white, and the seemingly natural markings, by adding more layers. The lightness of the construct has an evanescent quality. This is fixing a fluid map before it reconfigures into another.

Jane Hunter, Reciprocity, 2022

Looking at Jane’s pictures I think I know where she wants me to look. I think she is manipulating the viewer’s eye. “Yes to that”, she says, “but I like to use punctuation, make sure you see the full stop or the bit in bold. I want you to know where the important piece is that I want you to look at first, but also that there’s lots more subtle elements in the layers that you can find once you’ve looked at the first point. I suggest you can spend time reading the rest of it and looking at the more subtle elements…it’s not just ‘there’s the painting, I’ve looked at it and I can move on’. I hope you can go back and find more.”

Where does her inspiration come from? I’m checking reference points, but I already feel the main influences are her own highly sensitive senses and her openness as a “chronic over-sharer”. “Helen Frankenthaler is the mother”, she says, and she’s aware of a number of Frankenthaler’s followers. But she’s pretty much self-taught.

She didn’t go to Art School. She grew up in the edges between Renfrew and Paisley. She loved art – it was her only subject in sixth year – but she was torn between pursuing it and earning money to get on with life. After a short stint in an art foundation course at Paisley College, while working in a garage and then a pub, she took up the offer of full time work in the pub. Marriage and two children swiftly followed, and Jane got a job in Glasgow City Council’s HR department for twelve years, providing for the family after her marriage ended. She hardly thought about art for this whole period, and it took the confidence and nudging of her new partner, Sam Kilday, to re-activate her creativity.

Jane left the Council job and she and Sam set up a business together, designing, producing, marketing and selling textile based gifts. Meanwhile Jane started working on textile art pictures. It was on a trip to the Watermill Gallery, Aberfeldy, for coffee that Jane’s life changed. A chance conversation about their giftware business with Jayne Ramage, owner and gallerist, brought Jane’s artwork to her attention. Jayne Ramage was the first person in Jane’s life to describe her as an “artist” and the invitation to produce an exhibition for the gallery followed on the same day. It was a day that transformed Jane’s world. Later that year, half of the works sold at the exhibition opening; and the rest following swiftly.

Textile art to hang on walls became her key creative focus. Commissions arrived in quick order. Her work is in every room in a hotel in Skye, she’s featured strongly in the newly built Raasay Distillery Centre, and she’s featured on the walls of corporate offices and public buildings. The National Museum of Scotland have commissioned a replica of her textile geology map of Raasay for their own collection.

Jane Hunter, Geology, Raasay, 2018

Geology and mapping came to the fore in her textile world. She produced a follow up exhibition in 2015 for The Watermill Gallery based on the Moine Thrust, and she was commissioned by the British Geological Survey, Northern Ireland, to produce an artwork to commemorate their 70th Anniversary. On her kitchen windowsill there’s a collection of natural objects and she picks up a stone and relates the pattern markings to stresses in the basalt. She knows the rudiments.

She painted her plans for the textile works in sketches and sourced the fabrics on the basis of painting colours, but that was as far as the painting went until 2019. Then, on a family holiday to the Craignish Peninsula, she took a small watercolour palette and some brushes, sat on a jetty, and resolved to start painting freely and see what happened. After a few landscapes and paintings of objects had been screwed up, experiment and free expression arrived and she liked the results.

That’s the back story, and it informs the work she’s producing now. She’s not been schooled or peer-pressured into any approach, she’s found it herself, and it speaks of her, not of influences. When I mention other artists who work in similar areas, mapping, using bold flows of colour and abstract forms, she doesn’t know them. She’s a relative novice in painting. It’s not a chore, a job, a routine: it’s a joy, a way of expressing pleasure in life. The work has a freshness, a naturalness, a sense of being alive itself, an immediacy and fizz that transmits to the viewer who ‘gets it’ because they’re alive to the same things that thrill Jane: water, sky, wind, sea, rocks, plants; the exciting way they play on the senses; and the deep human feelings they can produce.

The colours are all chosen in advance and the colours represent various emotions. Does Jane have to get herself into the right emotional frame of mind to be able to paint?

“There are definitely times that I just can’t paint. There are times where I say that I’m not going to do anything because nothing good will come. That’s always to do with my frame of mind. I have quite complex emotions. I feel things more than a lot of people. Good things and bad things. I’m always happy that I feel good things so much, but the flip-side of that is that negative things equally impact. So if there’s anything that shakes my brain a wee bit, I don’t try to paint, because I know from experience that nothing good will come.”

Jane Hunter, Between Us, 2022

“It’s not even about feeling good, necessarily, because I do process a lot of thoughts and feelings whilst I’m painting. I couldn’t process personal thoughts though, for example if something happens in my family I couldn’t paint through that and have that in the painting because that’s what I would associate with it.”

“The process of painting grounds me back to the bigger picture. That’s what I’m painting about mostly. Nature, that’s the bigger picture. So I become less bogged down in the minutiae of day-to-day life and things that get you down. I go into the studio and I go ‘right, OK, let’s put that aside and think about these bigger things that I’m making paintings about’. I am able to do that. At other points, when things are bad, I can’t.”

How about when things go wrong whilst she’s painting?

“There’s a point in almost every painting. I know most artists say this, but there’s a point where I say ‘I hate this and I’m going to throw it in the bin’. I go through that with every painting. I almost see it as part of the process. I need to work with that chance thing that’s happened, or what I might see as a mistake, like I lay down a layer and then I go, ‘dammit, I wish I hadn’t done that’, but then I think, ‘Ok, how do I work with that and move forward with it?’. Thinking about this question there’s also an element of not wanting to waste materials. I need to persevere with this because I don’t want to waste the paper or the canvas. Obviously when it was the fabric I was working with, that was an expensive material too, so I didn’t want to waste it.”

Jane’s not one for waste or clutter. If it’s something she wants to keep it needs to be organised, stored, available for use. She welcomes mistakes and chances as long as she’s got the ingenuity to bring them into a controlled environment, and here’s where the negative space of raw canvas or paper comes into play.

Jane Hunter, A Collective Embrace, 2022

“Thinking about taking chances, I rarely touch the edge of the canvas. You can’t do that without intention. There are some paintings that I have where the paint reaches the edges or spills over the edges, but mainly I’ll decide to do that, so I think that’s part of me wanting to bring order and neatness to most things. There are parts of it where I can’t have control, where the paint will do what it wants, so if I’m tipping, moving, blowing, it will do what it wants, so there are bits that I really, really can’t control, but as the layers build, what I’m doing is to control and neaten as it comes to an end.”

“I think there’s an element of my personality in making the pictures neat, but I’ve realised that as much as I would like there to be this big element of chance, there’s less of that than I care to imagine. I think I’m more in control of it than initially I thought. And that gets back to my personality. With raw canvas, and working on paper as well, I really like to keep that negative space clean, so I need to have control because you can’t go back, once that raw canvas or paper has a mark on it, you can’t take it away again, so I have to have some control over that element if I want to keep the negative space.”

Does she like the purity of embracing these marks with a pure surround?

“Yes”

And she still likes textures?

“I do still dip in and out of textiles. I’m currently making a commission piece in fabric. It’s just not my main focus any more. The textiles gave me texture. One of the fundamental aspects and the appeal was that I always ended up with an object. I got 3D elements to the work quite easily, and with such a different media of really watery inks, it’s as though I’m working with the layers and marks to find that again. It’s more of a challenge to try and create that texture rather than it just being handed to me in the first place. I’m trying to do it in a different way with the paint. Maybe it’s more depth than texture in terms of the layers and patterns, but I still strive to have texture.”

Jane Hunter, Water Remembers, 2023

Looking at Water Remembers, there are textures everywhere, albeit those created by thin overlapping veils of watery pigment. There are wave stress patterns; a firm but broken ruled line; varying paint densities, some overlapping, some bleeding; a four note chord in blue-green; balanced by the brightest, thickest final mark: a gorse yellow stamp of great confidence.

Fixing her mind on the thrill of a wonderful experience; wanting to share it; looking for the perfect chord, shifting around the harmonies; tilting, brushing, pushing, and withdrawing diluted pigments; taking risks, making mistakes, then turning them into positives, tidying up, and making the process and the result feel completely organic and natural. That’s what Jane Hunter does in 2023, and it makes you feel good, refreshed, more alive, as though you were taking a wild walk or swim or sail on a beautiful day on Scotland’s west coast.

It’s art that re-sets your compass.

Jane Hunter Confluence is at Tighnabruaich Gallery from August 12-September 3, 2023

Update: March 2024: Jane has a new series of works on paper, In Pursuit of Light, which you can see (and buy) online at www.janehunter.art