Janet Melrose: Going For It

A challenger, a questioner, a risk-taker. As Janet Melrose’s artistic career has developed, so too have these attributes. In January’s RSW show, the seasoned attendee who can spot an artist’s work a mile off would be surprised if they could recognise Janet’s works. They were quite unlike what she did last year, and indeed the year before that. They’re unlike most of the other exhibits, too. Things have changed for Janet Melrose. In her late 50s, her experimenting got tougher - she looked hard for an essence - and right now she’s searching in dust. Is she lost? Roger Spence went to Crieff to find out.

Janet Melrose. Dust is Political. 80 x 60cm. Watercolour on mulberry paper, on canvas support. 2024.

Janet Melrose is engaging, caring, invariably positive, an attentive listener, and a quick-fire talker. She can pack a lot of words into a few minutes. She clearly likes people and company. She’s the kind of person that strangers might approach in a café because she has an aura of empathy and a readiness to engage.

I’m being bold in these assertions, and I’m following Janet’s current diktat to “go for it”. I’ve probably spent no more than six hours in her company.

What I come to learn is that she can take on stress and responsibility, but she’s not looking for it. Her husband, Scott, takes the key role in their well-appointed kitchen.

When I suggest she might live the lonely life of an artist, she chides me: “Not a lonely life! My friends and fellow artists would chuckle at this. I love being on my own to work and can find being with folk too much sometimes. There is a balance to be had.”

She teaches, she mentors, but mostly she paints; nearly every day from nine to three, or thereabouts. The old school day timetable stands.

School days are significant. Since her life stopped revolving around her children’s educational activities, she’s been back to school, as a student. She’s nostalgic for her early school years; increasingly using memories from her own early childhood as inspiration for her art work.

Her studio is a new-built timber-frame construction, high-ceilinged with windows looking north across the River Earn’s flood plain to the hills above Loch Turret. Her section of the building (Scott has an office next door) might be square, but it’s hard to tell because there is so much stuff in it. In its current configuration it’s like a roundabout with walls: a single carriageway roundabout at that, with only a couple of spaces in which you can squeeze past another person.

Janet likes collecting and she’s got a taste for occasional curating and cataloguing. The latter elements might be currently subservient in her studio practice to her “going for it” and “pushing a bit”. There is clear order around an easel. I suspect she’s one of these people who knows where the smallest studio prop or piece of Japanese paper might be in the congeries.

When we go inside her house, once we’ve passed the inside-outside interface of boots and sticks and bags and stacked pictures, we’re in her kitchen/dining space; clutter-free, design consciousness everywhere, with neat piles of archive material laid out on the table for me to see.

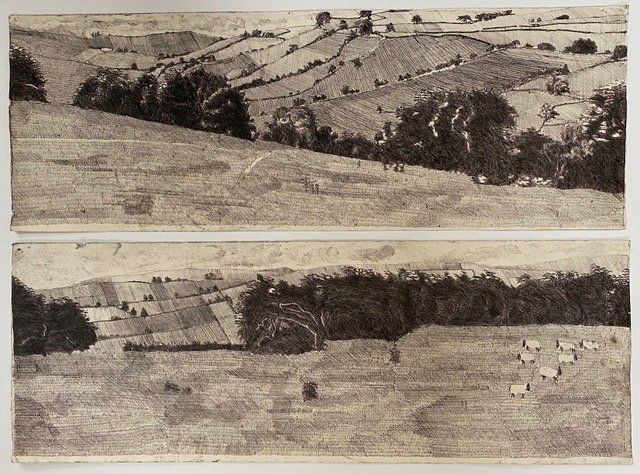

Straight away the eye is drawn to a couple of wide sketchbook pages that fit together to create a two-feet-wide landscape drawing – in biro – of rolling East Lothian farmlands. Next to it, there’s a sketched drawing of a terrace of houses and another of the functioning Water Mill at Aberfeldy. There are dates on them: 1980. Janet was sixteen and she had an advanced eye-to-hand facility by that age. She was also already conscious of dating drawings.

Janet Melrose. East Lothian Landscape. Ink (Biro) on paper. 1980.

She told me that she sat alongside her father, Bill Melrose, and they drew the same subject side by side. In the entrance hall, there are two of her father’s paintings of decaying mine buildings at Newtongrange, and Janet points out a striking small oil in blacks, greys and whites of a Leith street in winter, which her father painted. She grew up with a father who was passionate about drawing and painting. He was an architectural technician and then an interior designer by day and an accomplished artist at night and weekends. He went to Edinburgh College of Art in his 50s and then became a professional artist, exhibiting at Stenton Gallery, amongst others.

Janet was brought up in Edinburgh’s seaside suburb of Joppa, with East Lothian on the doorstep. She recollects promenade walks to fairgrounds and Portobello, but she has a strong memory of the atmosphere and sounds in her grandparents’ basement flat; traffic on the cobbles outside, light angling down from the street, highlighting the dust in a room that captured Scottish working-class life in the pre-mass-media/global capitalist age: open fires, sideboards and doilies. These images are at the core of her current practice – but we’ll come back to that. Here’s a drawing of her sister, nine years younger, watching TV in 1980.

Janet Melrose. My Sister Watching TV. Biro on paper. 1980.

She arrived at Edinburgh College of Art in 1982, and her immediate impression was that she was about to grow up. The signal came on day one, when she found out they had a coffee break: a bit of a grown-up revelation for the young girl. She’d been encouraged in her art at school, but her self-esteem was fragile. Undiagnosed dyslexia had plagued her throughout her school career.

Looking back on her time at ECA, she loved getting into the hills when John Busby led a minibus packed with Natural History Drawing students out into the countryside, usually south of Edinburgh.

“That was freedom for me, a game changer, just to be able to get outside. It is quite difficult for females to have that sense of freedom, to be able to take yourself somewhere. I’m still quite conscious of being out drawing on my own. You had people around you. You knew who everyone was, but you were also able to sit and get on with your own work… and there were all the conversations between us, and John. He was a really quiet man, but anything he said, you remembered. He really championed what I did. After second year I saw him off and on, and later on he set up a bird drawing course after I’d graduated and I did that. I’m not a wildlife painter, I’m never going to be a wildlife painter, but I did learn a lot about observing, and then I could flip things around, I could experiment, I tried out all sorts of different things, and John was hugely encouraging of that. If I had been a bit more sassy then I could probably have taken things a lot further. I’m doing that now…”

Janet Melrose. Detail from Journey of the Birds.

Janet also remembers Roy Wood’s drawing classes with fondness, but for the most part she feels that she didn’t learn as much as she might, and she perhaps wasn’t bold enough to follow her instincts.

She graduated in 1986. “Then I went to Florence, but not immediately. I got a job working in hospital kitchens and I was working at Edinburgh Zoo, and I was saving money, and then John again came along, and suggested that I apply for a bursary, which I did, and I got an Andrew Grant Postgraduate Scholarship. That gave me some money and I enrolled at an art school in Florence. Again it was studio practice, but the tutors were right on you. We had all sorts of exercises, homework, the whole shebang, and I worked really hard, probably a lot harder there than I did in Edinburgh.”

“I learned a lot. And I also learned that I could enjoy aspects that I hadn’t enjoyed, like figure drawing. They were rigorous but there was a huge amount of experiment going on as well. We were encouraged to do that. So if I felt like doing a big figure study with a rag dipped in ink, which doesn’t sound very revolutionary and it isn’t, but I could do it. I probably could have done it in Edinburgh but I didn’t do it. I needed to be in Florence with a group of people who were much more willing to ‘go for it’, basically.”

“At Edinburgh there was very little input. There was no conversation with any of my tutors, and I mean that. It’s not an exaggeration to say that I could have exchanged a couple of sentences in my fourth year with the gentleman who was overseeing my studio. But with John, I could have more of a conversation. I could have done more, definitely, in hindsight.”

“I think it’s just an age thing. I was just too young to be there. I had the facility to do things, but I didn’t have the conviction… The hyenas and the birds and my way of expression through these motifs, that is what I should have gone with, because that was me. I don’t know what happened but I went down this other road, which was much quieter. It didn’t marry up. There was a disconnect at that point. And I think that I’ve spent years trying to bring it all together again, and find myself in that.”

Finding herself has been a lifelong quest, but one that Janet feels she has achieved in her current practice, thanks to a third educational establishment: Leith School of Art. Her mid-life crisis moment, fuelled by Covid lockdown, led to her enrolling for the Contemporary Art Practice course at Leith in 2022.

What was she looking for? Surely, when she looked at paintings that she’d produced she thought to herself: “no, that one isn’t me, but this one is me”.

“I don’t think its as simple as ‘that wasn’t me and this is me’. I just think there’s something that I need to say and do which pushes things a little bit further. There’s a lot of me playing a little bit safe, but I don’t feel that. For instance, this piece called ‘Wrapped’…

Janet Melrose. Wrapped. Mixed media (plastic, cellophane, cotton thread, pink ribbon, and enclosed [in pieces] written note). 2023

We are looking at a contemporary art practice still life, an assemblage that has probably been repeated many times over the last hundred years, but never kept in tact, and so every new one is fresh, and of course, touched with the personality of its creator. It was shown at the SSA Treasures Exhibition at Gairloch Museum in 2024.

“Basically, when I do something like that - which is about collecting all the things I had when I was at Leith School of Art and then folding it and creating these little packages - I think this is so what I want to do. It has a playfulness about it. It has a process that I went through. The final piece feels right. It’s a combination of things. I wouldn’t have necessarily thought about it, but I needed to put myself in that situation where you’ve got that freedom to say, you know what, I’m just going to do this, and I do it.”

We’re vaulting over nearly forty years of artwork, during which time Janet has always questioned and tried fresh approaches. We’ll examine what she’s done shortly. But in January 2025, the context for talking about Janet’s career is that she thinks she’s finally cracked it, and that what she did before 2022 when she voluntarily “collapsed her practice”, she’s still proud of, but thinks that it’s history. There has been a revolution since then.

Maybe what she likes is not so much being herself, but being free of any type of shackling. There’s no safety net and no rules. Her work doesn’t have to be attractive or beautiful, it doesn’t have to have a message, it doesn’t need to fit into a gallery concept, or a selling concept.

“When I was at Leith School of Art, in the last weeks of the first year there, I realised that all my stringing ideas together that I’d done every single week right up to the end resulted in a pile of material in front of me, and I said to myself ‘you know what, I’ve been making this piece throughout all of these months. I haven’t suddenly had to put myself under pressure to make something’.

“One thing I took away from LSA was that all I needed to do was to show up, put something in place, give myself something to do and get on with it. Easy. No stress. And I apply that to my paintings now. The painting on the easel in my studio, that’s a good example. It’s been on the go for a long time, because I built up layers of different gesso material, and then a day or two ago, I thought ‘I know what needs to happen here, put in these broken fractured surfaces’, and that was it, it arrived really, really quickly, and that’s it, job done.”

Janet Melrose. What’s Lost, What’s Found. Acrylic on paper, on canvas support. 122 x 92cm. 2025.

What’s the job?

“The job is just the making”.

Does she want to take the stress out of thinking about, and having to come to, a conclusion? If your practice is a kind of an ongoing laboratory, everything you produce has value if you’re learning.

“I’ll take that: an ongoing laboratory”

You don’t have to say to yourself, “this is going to be my defining work of art”. You can take it or leave it, you might learn something from it and you might not…

“I think that’s absolutely the case…”

We look at another group of images and they are all collections.

Janet Melrose. Free Radicals. Starched and coloured crochet pieces. 2021.

“Collections are really important. This is second year at LSA. This is part of the dust project. I’m collecting different textiles and making drawings from the textiles, and I started to get interested in the textiles themselves, all of these crocheted pieces. I had been making a rubbing of one of them and a carbon graphic got on to the surface, and I thought, ‘oh, that’s interesting’. I started to play with it, and over the months I did different things with it, so when I was using rice starch to put mulberry paper on to canvas or board, I took any leftover rice starch and used it on these pieces. I was dipping the material into rice starch and laying it over other objects. It solidifies and makes these structures harder, but they’ve still got a malleable quality that I can squish up and let them re-form. So I ended up making a whole series of them and I’ve called them “Free Radicals”. That references looking under a microscope at dust particles and all sorts of other stuff, like detritus. I’ve got quite a big collection now that I am going to exhibit going forward.”

Is it possible to collect anything less fashionable than doilies? Janet has spent many hours searching and finding; she’s applied her learning from almost forty years of practice to what she’s found, and tried to make the finding meaningful. But most of these human manufactured products are intrinsically ugly (for example, packaging waste and discarded gardening tools), or they are cultural rejects such as the doilies. She also experiments in repetition and multiplication, pressing out hundreds of paper cups and making them into different shapes; pressing her finger into ink and making fingerprints on paper, repetitively line after line; writing the same word backwards hundreds and hundreds of times, and piling up the completed sheets of paper.

How about this?

Janet Melrose, Dust is an Archive. 70 x 60cm. Watercolour on graph paper.

“Yes, this is part of me being at Leith School of Art. Prior to me really embarking on the dust project, I was interested in chance and serendipity and putting a process in place. I think I told you before that I had an idea of throwing a dice, 1-6, and I had different options for what I could potentially do, so I would throw the dice and it would correlate with something I had listed, and then off I went. So I used things like a French curve to make this drawing, and then just repeated and repeated, and then started to fill it in in a very methodical way. Again, it’s a repetitive process. This was me thinking about clouds of dust after reading Jay Owens’ book, Dust.”

What was she aiming to do?

“I hadn’t a clue. The process just unfolds.”

It was like an experiment from which she was hoping to learn something?

“Well, whether I learn something or not doesn’t come into it, not at that stage. I do learn and I learn loads about all sorts of things. I also learn what I need to put into place to allow things to happen. So there is this playful approach, and play is really important to me. I read a pamphlet called The Playful Manifesto by Max Alexander and that really consolidated the importance of play for me. Its something I’ve touched upon with workshops I teach and also with my own art practice. It’s interesting because all of the time doing this throws up unexpected things that I can’t plan for, and that’s really what I want to do. I don’t want to know too much. I think I could plan and that would just scupper everything for me. I’m far too good at planning… potentially planning.”

She uses the words ‘play’ and ‘playful’ a lot. We talked about a laboratory, about experiment; about it not mattering whether her making is a success or not. Everything is a success, because Janet’s done it: she’s made it and there’s benefit in that. But parallel with this, every morning she goes outside her studio and makes a watercolour painting. She has hundreds of daily paintings in piles; and she’s got two or three canvases that she’s working on at the time of our meeting. Are these practices feeding into each other, ideas shared? Are the found objects feeding into the other practices, because the watercolours are consistently landscape watercolours, as we might see here in Iona? This is ongoing practice.

Janet Melrose. Iona: View from Ferry Terminal. 20 x 22cm. Watercolour on paper.

“This is me just pitching up. It couldn’t be more simple. You sit yourself down. You get yourself sorted and you make a painting and have a coffee. And I love that. It’s nothing more than that.”

It’s stress-free.

“It is. But the other things I’ve made stress-free, too, by adopting a different practice. For example, there’s the Foundling stuff, a project where I collected everything I found from the river.”

“That was like an archaeologist making a record of objects found on a site. For the most part they will measure it and then make an accurate drawing of it. In many respects that process and this are much the same in that all I have to do is make a record. It’s nothing fancy. Eventually, once I’ve accumulated a lot of objects, I’ll be annotating them. That’s a little fun part for me, because that’s definitely me going a little bit further. This is not just a record of what I’ve found, this is a kind of installation work, or something.”

Janet Melrose. A Repetitive Process. A4 photocopy paper. 2021.

“These were pieces which I made during Lockdown. Its was part of my daily routine. A repetitive exercise involving folding sheets of photocopy paper into cylindrical shapes for ten minutes each day until I had amassed a pile of them. This photo shows a fraction of what I made. I kept some and recycled the rest.”

She could configure and re-configure and play with mass-planting like a landscape gardener. Is there anything that she does that’s not playful?

“No. That’s what I want to do. I’ve arrived at the point where I know what to put into place to allow me to do what I do. That’s my practice.”

When she says she knows what she needs to do, does she mean the psychology?

“Yes. I’ve got these tools that I can bring on board to allow my take on things to happen. They act as a catalyst.”

The paintings that Janet is making right now are in a series which she is calling her Dust project. This started in The Customs House in Leith, whilst hanging an exhibition there. She saw a rug that reminded her of her schoolchild-self playing in a tent that her grandparents had created by hanging a rug on a washing line in their back garden. That spurred her to think about her grandparent’s house and the dust in their front room, lit from above. These faded memories and the faded rug in Customs House merged with another ongoing fascination, exploring a house close to her home that has been left to decay, with many domestic objects and decoration still in situ and the forces of nature imposing themselves, either through the rotting desuetude of weathering or through the growth of vegetation and fungi and insect and animal life. Perhaps Janet understands more and more that nature’s beauty easily surpasses clumsy human aesthetics.

Janet Melrose. Henge. Watercolour on paper. 56 x 76cm.

“I went to some of the prehistoric sites around here, the henges, the standing stones, but also at the same time I was looking down at the algaes and the lichens on rocks, and seeing parallels between an aerial landscape and a landscape that was growing on that surface, mirroring that larger landscape. I made a whole series of these.”

This is the practice that she’s left behind: the questing; the bright, light painting that was searching on journeys through nature and human emotions. Was that very stressful? Perhaps those very sparse marks were the source of tension, because one could so easily screw up the whole concept?

Janet Melrose. Winter Walk. 152 x 122cm. Acrylic on paper.

“No, no, I think I’d learned enough about what I needed to do, so that when these paintings arrived that was already in the process of happening. They’re done quite quickly, quite spontaneously. I don’t allow any of that negative stuff to creep in. I’m very present when I make that work. There’s less of the difficult work happening these days, because that isn’t my process. I’ve had all the years of experience, and now when I make a piece of work that stuff is edited out. What works and what is not working: I almost don’t understand it anymore. I will invent something. I will resolve the problem and ‘Hey presto! Away we go’”.

Does that mean that she doesn’t have any quality control?

“I do have quality control. I definitely do. I think this is the most difficult thing to explain. It comes down to the way I’m working at the moment. I will recognise things where I haven’t gone far enough, and I’ll go ‘you just need to go for it’. Sometimes there’s that little bit of holding back, and I think that’s part of my quality control. I need to blast it with a hose or get rid of stuff, rather than being comfortable arriving at that particular position in a painting or a drawing. That is a big learning thing.”

Janet Melrose. Foreign Body. 150 x 120cm. Watercolour on mulberry paper, on canvas support. 2024.

Does she know when it’s not right?

“Yes, I do. It’s not to do with it not being right. It’s to do with me not going far enough. Somebody could come along and say ‘That’s fine, Janet, that’s working’, but if I don’t feel that, it’s going to get hauled out and put on the grass, or the hose is going to be out and I’ll blast it. And that’s when things get interesting, when I don’t have control over things. We talked about my facility to draw and paint, but it only takes you so far. I’m quite interested in people who would describe their practice as ‘not drawing’ or ‘not painting’. That opens up possibilities. Some artists or musicians are technically incredible, but they’re not expressive. I think when there’s a marriage between technical skill and understanding what you want to say through that piece of music or that painting, then you’re onto a different level. I’m not letting myself sit too comfy.”

Change has always been a key element in Janet’s work. She’s restless and wants to challenge herself. Up until her recent epiphany, incremental developments of her practice could be followed through an evolutionary process. Whilst she describes her current activity as a “collapse” or a “crashing” of her previous practice, it’s got an explosive quality to it too. All of her life’s work is in the air, and Janet is thrilled by the fireworks. Alchemy is in process and she’s not sure how it will settle.

Its time to review that life’s work.

Looking back, Janet says her early life feels somehow as though it was programmed without her being involved. Janet was challenged by words and diagnosed late in her school career as dyslexic: too late to avoid the anguish and stress of being unable to grasp some words, and spell a lot of others. Janet’s body tightens and screws as she explains it to me. Perhaps this was why the language of drawing and painting appealed. And perhaps her father’s role model was very strong.

Janet Melrose. Young See. Oil pastel on paper. c.1990.

From school to college, it was Elizabeth Frink’s sculptures and drawings and paintings by Graham Sutherland and Paul Nash that were her outside influences, and John Busby’s natural world too. She liked “powerful, expressive work” at college: Frink, Muybridge photographs, Germaine Richier’s work. “I have always been interested in sculptors.” However, she feels that she emerged from formal education, to a teacher-training course at Moray House, and then to teaching at an Edinburgh boys’ school, almost as though she was on a treadmill.

She got married and soon had two daughters, giving up her job to become a professional artist as well as mother. Even then, her artistic life consisted of the two hours in the evening that she carved out for herself away from child care and house management. What was she producing at this time? Large canvases of landscapes, she says, and animals.

Janet Melrose. Hyena. 76 x 56cm. Mixed media (sheets of acrylic and watercolour crayons on watercolour paper).

She has no records of the landscapes but the hyena that she first met as an art college student gives us an idea as to how she approached animals. “This image is of a series of drawings I made from the hyena at Edinburgh Zoo. I cranked up the colour after seeing Robin Philipson’s work.

“I went to Edinburgh Zoo a lot. I had a little job there where I helped in the children’s farm and did printmaking with them, and I was allowed to stay behind and wander around once the public had gone. I got really interested in this solitary hyena, a really very distraught animal that paced around in the cages, and I made a whole host of work based on this animal. I regret not taking this further. I really think my degree show would have been so much better, so much stronger, had I gone with my idea of using an animal or a bird as a motif to express something through. I really enjoyed this work.”

Whilst hindsight makes her gloss over her early career as producing work that wasn’t really her – that it was what she had been programmed to produce – that was far from what it felt like at the time. She exhibited at Peter Potter’s Gallery in Haddington, in the Kingfisher Gallery in Northumberland Street in Edinburgh, and she won the “best student” prize at the Glasgow Garden Festival painting competition. She quickly established herself as an exhibiting artist in professional galleries, though there were always moments when she needed a sale to be able to buy the next batch of paint.

Janet Melrose. Greyhound and Lily. Acrylic on board.

“That was the neighbour’s dog, and that was basically repeating the greyhound shape. It was called Penny. It was just one of these playful things I did one night when I had a couple of hours in the flat in Comely Bank in the 1990s.”

One of the items laid out on Janet’s dining room table is a typed draft from an application to the Scottish Arts Council in 1997. It’s instructive to print it here because it tells us how Janet was thinking at the time:

Two years ago, after the birth of my daughter, I embarked on a series of paintings which were unlike anything I had made before. I knew that if I wanted to continue painting, I would have to change my way of working. As we established our new routine, it became apparent that night would be my time for painting, and that I would need to be very self-disciplined if any paintings were to be produced.

I was very used to working out of doors, working during the day and collecting subject matter from far and wide. My subject matter then changed to the environs around our flat itself. I watched and painted the traffic, people walking their dogs and the delicatessen and hat shop. I saw all of these through partially closed curtains and shutters. My paintings, in acrylic and oil-bar, I hope have an intensity about them, which describes the moment of time in which they were captured.

I can no longer afford to be self-indulgent, I do not know when my daughter will wake up next, so I must paint with as much energy as possible, capturing the images I see.

She couldn’t indulge herself. That’s an interesting statement when considering her current thinking. As she says in the next paragraph, she felt “forced” to do things by deadlines, exhibitions, perhaps expectations.

I was asked by the Kingfisher Gallery to produce some recent work for a solo exhibition to be held in March 1998. This forced me to focus on a specific objective, especially with the limitations of restricted painting time. The opportunity this exhibition gives is more than just a chance to exhibit work, it has pushed me to experiment with new subject matter and ways of painting which will further my work for the future. It will help to justify the desire and indeed the need to continue to paint and progress, irrespective of the prevailing circumstances, learning to adapt to whatever may be presented.

Janet Melrose. Incense Sticks and Chinese Slippers. Acrylic on board.

What came rushing in were floods of vibrant colour, symbols and motifs that she had gathered on holidays to Thailand. She went three times, staying with an old Edinburgh friend. Animals and birds were subsumed in large tone poems where collections of images floated in intense colour.

Her colour harmonies attracted attention from interior designers, and galleries with buyers excited by her bold and intense tonal chords and her variegated image patterns. Her paintings were featured on the STV Home Show in 1998.

The world of design and architecture would soon become a large part of her life. A solo show at Strathearn Gallery brought her to Crieff and it was on a journey there that she and Scott spotted an old mill for sale that could be the renovation project they had been dreaming about. They made an almost instant decision to go for it, and it transformed Janet’s art practice. Living in a building site had its limitations, but they were compensated by becoming more at home in Perthshire, exploring the countryside rather like an animal would get to know a territory. Her friendship with Anne Wegmuller deepened as they walked, talked, and drew together. She credits Anne with helping her to develop her confidence to keep refreshing her practice.

Craigie Aitchison’s work was admired, absorbed, and made its mark on the Melrose oeuvre. The fields of colour got bigger, the objects simpler, firmer in outline. Janet’s dogs continued to feature, but one of them, injured, became a motif for hurt.

Janet Melrose. My Studio Chair. 122 x 122cm. Acrylic on board.

Having a custom-built studio must have changed her working practices somewhat. A cleaner, simpler, more spacious look was evident. Scott’s business interests in Italy led to regular visits there, especially to Assisi, and the idea of pilgrimage, and taking an ‘invented’ character (possibly herself) on such a journey, was intertwined with Italian images as well as Scottish ones. Pilgrimage was her conception, but she still didn’t have a sense of where she was going. She was still looking for direction.

The impact of nature and living with the countryside all around her was a more powerful influence on the compass. The walks with Anne Wegmuller chimed with the exploratory mind and the concept of searching for and looking at motifs and symbols that described realities both physical and emotional. The artist in Janet was continually making tracks through nature and through life, passing by and recording experiences. “In a sense I was taking myself on a guided tour, asking myself, ‘What does it feel like?’, or ‘Why am I standing on a rock in the middle of a stream?’”. The process helped her create a sense of place, perhaps even a sacred space, for herself in a new environment.

Janet Melrose. Flow Lands. 80 x 60cm. Mixed media on canvas.

The floods of intense colour thinned and then gave way to marks on white paper, with many pictures completed without Janet coming close to touching the edge. She started to have difficulty with rectangles, and felt the need to work away from them. There could be dense clusters and repetitive marks, but the overall sense is one of discarded clutter, and that brighter, lighter, airy world where colour could be what the printing trade used to call ‘spot’, and it could be a signal for a strong dissonance as well as a balancing harmony.

Meanwhile, Janet’s status continued to rise, with exhibitions at Union Gallery in Edinburgh, and then in 2011, election as a member of the RSW.

Almost every day throughout this period, Janet was asking questions about what she was doing and why. And her answers were all articulated in what she made (“made” now, because her thinking about art incorporated three dimensions in parallel with the traditional two). There were galleries to send work to, the annual RSW show to push herself for…

For her, the RSW annual exhibition is a special challenge. Up to three works can be submitted and sometimes there are space restrictions. “I see this as an opportunity to test ideas (and risk) and see how work looks and reads together in a space. For six years, up until this year, I exhibited my paintings in the Sculpture Court which allows the work to be seen together and not spread between different galleries.” She treated the RSW show as her non-commercial curated exhibition, not necessarily offering new work, but trying to curate a cohesive presentation across her three pieces.

Janet Melrose. Evidence of Burning. 150 x 150cm (x 2). Watercolour on paper. 2023. Shown in sculpture hall of the Royal Scottish Academy, Edinburgh.

Each time she moved on her art approach, she looked for and needed affirmation. Anne Wegmuller and some of the lifelong friends she made at art college continued to be important in assuring her of her direction. The Dollar Summer School which she taught on in 2015 was a huge self-confidence boost too. She enjoyed interacting with other artists, including Claire Harkess, testing ideas out and having creative fun with her peers.

By 2019, however, the pressures of exhibitions and galleries were beginning to exhaust; and round about the same time she had a substantial release from a significant personal commitment. She decided that her solo show that year would be her last. She wanted to discard responsibility. For Janet, “being responsible was about showing up, listening to what was being said to me and running with it. I finally decided I was doing things the wrong way round. I tied myself in knots knowing I had an exhibition to deliver. Instead, I just needed to make the work and then approach galleries.”

“I crashed my art practice. The sense of relief was palpable and profound. I had time to catch my breath, take time to sort myself out.”

“I had a conversation with myself: ‘Small steps’. ‘No demands’. ‘No judgements made’. ‘Simple, repetitive actions over however long.’ It did the trick!”

Unfortunately – or perhaps fortunately – for her, Covid and lockdown were soon to arrive and she not only found herself unable to meet artist friends (or any friends!), but there were no public exhibitions.

Like many other people she started looking at the self, and in particular herself, and she became her own commissioner, buyer and critic. The internet was the outlet and the opportunity, and it was here that she found a small artistic offering from an artist in Portobello, to be sent by post in return for £5: a box of artistic inspirations, with instructions. This little parcel turned out to be the fuse that lit the explosive device that she had been building. It led to her ending the years of development and gradual change, and revolutionising her practice to start afresh with herself as the starting point. There was an element of wellbeing in this decision, but there were hosts of challenging philosophical and existential questions as she worked her way through the contents of the box.

The box had been sent by Jenny Pope, Portobello-based ceramicist and conceptual artist; and Jenny was also offering life-coaching and mentoring for artists. Janet quickly saw a helping hand in thinking about and resolving what she might do. Jenny’s box of bait was enthusiastically reeled in.

In that strange Covid-19 induced world, Janet’s epiphany evolved through their online Zoom discussions. She has never met Jenny in the flesh. But the consequence of their talking and Janet’s thinking was that she decided to enroll part-time at Leith School of Art on the Contemporary Art Practice course.

She told the school at her initial interview that whilst she was signing up part-time, her intention was to give wholehearted commitment to her new learning. She was going to set aside all of her historical baggage, dismantle her gallery commitments and her current practice, and be ready to absorb new concepts with an open mind.

The course was run by Rachel McBrinn, and Janet is pleased to tell me what a wonderful experience it was for her and her 10-12 colleagues in the class. There was an interesting range of visiting lecturers and practitioners with whom they could interact, and every week there seemed to be a new skill to learn, and a new way of thinking to be considered. Janet didn’t have any of the skills required to take on many of the activities, but she threw herself into the new and the novel in an unquestioning way. She particularly loved the video-making element and feels that this has informed her painting. She also liked the introduction of chance into her work, especially the notion that the choice of what she did at any one point could be decided by serendipity.

This sounded like a discarding of responsibility to me, but I think Janet’s answer would be something along the lines of “yes, but it challenges me to respond creatively, and to develop skills to find positive solutions to the events unfolding. It means I’m always being an artist, not just someone who repeats the formulas I’ve already mastered.”

Like so many artists and theoreticians in art history, when faced with the big questions around ‘why?’, ‘who for?’, and so on, Janet resolved to look back before her schooling for inspiration. Others have chosen “primitive” masks, pre-Renaissance practices, marks on Greek pottery or cave painting, but for Janet, exploring childhood memory, and the relative purity of early year experiences, was her way of starting to re-examine fundamentals. We’ve talked about dust. Repetitive pattern making was unearthed and revived as well.

She’s also tackled her young issues around words with a small piece that she produced with a stone hanging inside of a cage, which she called ‘The Weight of Words’. Related to this, she’s made three piles of very thin Japanese paper filled by repeatedly writing the word that gave her so many problems at school – “with” – backwards, right to left. She liked the pattern: htiwhtiwhtiw... And now she’s placed these paper piles inside a box and called that ‘Weight of Words’ too.

She works on these memory ideas in a graphic way, putting the memory in the centre of her writing paper, enclosing it with a line, and then ‘walking around it’, reviewing its different qualities, and how it communicates, how it connects.

Janet Melrose. The Weight of Words. 30cm. Painted stone suspended on wire within wire cage. c.2022.

“I was reflecting on the words used against women accused of witchcraft as well as the harm words can have on an individual. I had been listening to BBC Sounds: Witch by India Rakusen and The Witches of Scotland podcast. Both excellent.”

Her liberation seems complete. Through her teaching activities, she is in a small way freed from the need to sell paintings. She is a visiting tutor at the Paintbox School at Cockenzie House, teaching throughout the year and doing week-long summer courses. She continues to work for Wild Art Scotland, leading workshops on Iona. She says that the people coming on to those week-long courses know that they are going to be pushed and challenged by her to ask themselves questions about their art. Janet is equipped with answers.

Janet Melrose. Sketch of Iona Abbey. 30 x 20cm. Oil pastel on brown parcel paper.

Where is she today? She hasn’t lost her enthusiasm and perhaps infatuation with watercolour and with sketching. She describes how, for a period of time recently, every day she got a piece of paper, poured water down it, then added pigment and spent ten minutes watching its dispersion. She knows how water and pigments work. She feels that she can do most things she wants to do in watercolour. Sketchbooks are constantly on the go, and filled with landscapes from the world around her that many might regard of an exhibiting standard. “Simple, direct, no fuss observation – for the love of it.”

She feels she’s given up a lot and risked her career. For what? I think aloud that her dust-work might suggest that she’s in a bit of a fog. Far from it, she says: first and foremost, she feels much more true to herself; and she also feels that she’s got a greater sense of clarity about her recent work.

For a long time, Janet’s focus has been on nature and responding to it; now she feels the need to produce work from within.

Janet Melrose. Attracted to Dust. 60 x 60cm. Watercolour on canvas. 2025.

Janet Melrose. Fragments. 50 x 40cm. Clay with graphite and charcoal dust. 2025

From biro landscapes to powerful colour tone harmonies to Aitchison-inspired simplicity to sparse essays in nature and searching, and now this – the Dust project –decay, and interaction with nature and chance.

My bullet-point list of where Janet Melrose is in 2025 runs like this:

It’s all about play

Stress-free creativity

The ongoing laboratory

Mining memories of childhood

There is no right or wrong

Searching and finding

Collections/Repetitions

Chance - divesting responsibility

Satisfying the self - being “me”

No longer searching, but reacting

The need to push yourself further (but towards what?)

Dilapidation and decay - giving in to nature

Dust

Who knows what the future will bring? She’s constantly rebuilding it, and I suspect that next year another different ‘identity’ list could be written, and in 2027, another, and so on.

But alongside this, she’s going to be drawing and making watercolours of the flowers in her garden when they bloom, and the birds, her dogs, the landscapes around, as she’s always done; she’s going to be in Iona in the summer sketching the seashore.

These are the certainties. And she’ll be continuing to look for something more, and to push herself to something new. That’s almost a certainty too.

And if, after reading this, you still can’t get a fix on what Janet Melrose is about, don’t worry, that’s where she wants to be: un-tethered, free.

Roger Spence

Acknowledgements

With thanks to Janet Melrose.

All images courtesy of the artist.