In Retrospect: Malcolm McCoig

Malcolm McCoig’s name has been known by Scottish art lovers since the 1960’s in a range of guises: Greenock lad; Bob Stewart student and associate; expert screen printer before printmaking was mainstream; textile design teacher; collaborator with Arthur Watson in the set up of Peacock Printmakers; regular print exhibitor across Scotland and internationally; important player in the Art in Health Care movement; artist in residence in America; producer of large scale public textile works; and a painter whose work has often been publicly exhibited – especially in the west coast and north east. His work is in many public and private collections. About time for someone to review his artistic life and work, and Roger Spence has been talking to Malcolm at his home in Angus.

Festive Barriers with Full Moon

Significant Signs

Mark

Many painters and printmakers are distinctive and their styles immediately recognisable. Malcolm has both of those attributes, but he goes where no-one else does. His approach, his choices and his subject-matter are often not just individualistic, they're different. He sees art in the humdrum world of the everyday, the little joke, the ironical juxtaposition, the humble object that’s scarcely recognised, and by setting their shapes and colours in striking compositions, he creates work that makes instant and then lasting impact. The final images stand apart, sometimes suggesting influences, but rarely, especially with the paintings, any association with a school or movement.

His work embraces a range of disciplines: design, print, painting, textiles. They cross-pollinate, but the end-products all reflect a deep-rooted artistic character, independent minded, and strong enough to forge a singular and clearly defined path, identifiably McCoig, from 1962 to today.

The deep roots? He's open about his enjoyment of the work of Ed Ruscha, and word-play is one of Malcolm's weapons; Robyn Denny, Ceri Richards and William Scott are also admired. But their effect is limited. Perhaps the biggest influence on his work is his upbringing in Greenock in the 1950's. A hard world in which comedy and creativity were release-clauses from the social contract with the place.

Malcolm McCoig was born in January 1941 and grew up in a town where shipbuilding and sugar refining were still massive employers; importing, exporting, distributing, Greenock was a major port, and a manufacturing base for a wide range of goods, from barrels to furniture. Hamilton Street was a buzzing main thoroughfare, day and night. The McLean Gallery was a vibrant and dynamic art institution, which was busy supplementing their substantive 19th Century and early 20th century collection with a buying policy that meant that artists like Redpath, Morrocco, McIntosh Patrick, Cumming, and Crosbie were all represented. It was a stimulating art beacon for a young Malcolm McCoig.

He went to Greenock High School, where he had the good fortune to have the remarkable Alexander Galt (Note 1), then in his early forties, as art teacher. Malcolm found him inspirational, and he was a key influence on the young man. He may have spent too much of his youth drawing and painting; hanging out with the likes of Mike McDonnell, Alex Gourlay and Bill Bryden; and going to the cinema and dance halls. He played trumpet with school colleagues in the West End Jazz Band - and later graduated to the Savoy Jazz Band. Malcolm's focus was art and music. He didn't get the grades in his other subjects. It was always art school for him, and he made it to Glasgow in 1959.

His subject was Design. He had options to go in a number of directions, but Bob Stewart, the remarkable artist, designer, and teacher, was at the peak of his powers, and aged 35, running one of the most exciting departments in all of Britain's art schools - Printed Textiles. It was his passion and charisma that won Malcolm over, and shaped a strong element of Malcolm’s artistic and life direction.

Printed Textiles sounds a pretty niche area, but Stewart's practice and philosophy was all encompassing. His department embraced all of the artistic and craft areas in which he was personally interested: graphic design, drawing, painting, printing, ceramics. Erstwhile colleague, and GSA Director in the 1980's, Tony Jones, summed it up: "Some people in Printed Textiles didn't ever do any... Bob didn't believe much in a hard border between 'fine art' and 'design' .. his hero was an artist like Matisse. The ability of Matisse to make powerfully 'designed' pictures of big bold shapes and colours, rich in exoticism.. and then turn effortlessly to the paper-cut collages that were produced as textiles or finished as scarves... Bob saw that as the work of a 'natural artist', not a 'fine' one, or a 'designer-artist', just a wonderful artist who found different ways to 'apply' his art" (Note 2)

We need to remember that the 1950's and early 60's was a world of "Art Without Boundaries" - look at the modern book and record sleeve designs of the period. They were artworks in their own right. Advertising, Posters, Packaging, Decoration were all places where artists could make money, without necessarily having to compromise their ideas. Mass-markets and Artists came together for the first time and creativity was still seen as a core value.

Matthew

Detail from Three Dice, or A Wee Tribute To Bob Stewart

Malcolm recalls what it was like:

"The first 3 months of Bob Stewart's department was very difficult in as much as I didn't really understand what was being asked of me, and it was as though all the previous years of being taught "art" went out the window. A simple example was: why is the picture plane usually either the golden section or 1/3 to 2/3 divisions - why not something else? Maybe just half it! Then, being sent out to draw at the Botanics, half day a week with no tuition: what can you see, how can it be developed? I do remember I returned with drawings of knarled bits of wood, or knots on tree trunks and was asked to push them around - what to do and how to do it? Nothing about textiles design or how to repeat, just trying to make marks that actually ‘worked’- and always how to keep it lively."

The classes were small - only 12 students in 3rd and 4th years combined, and the contact time in the studio was no more than two and a half to three days per week. Malcolm remembers craft all day on Tuesdays - etching and lino printing; an art history lecture on Thursdays; and life drawing on Friday afternoons.

"We were encouraged by Bob to look at artists, rather than designers, for inspiration. He selected the ones he thought relevant to you. Well, he did that with me anyhow. William Scott, Nicholas de Stael... but one of the monthly highlights for me was seeing the latest copy of Graphis in the library: Milton Glaser, Andre Francois, Jean Michel Folon all came into my life at this point."

"Also, Bob's assistants, Bob Finnie and Bill McGeachie, were very influential during the three years I was in the department".

Chuck Mitchell, later to be another of Stewart's influential assistants, was a colleague of Malcolm's throughout his student days. Malcolm was the only person allowed to call him by his real name, Charlie. "He was a big gentle guy and Bob Stewart's favourite". They went together on the renowned Easter holiday drawing trip, which in 1962, their first year in Printed Textiles, was to Kintail. "It was a completely new experience for me, and to see Bob in action, out all day in all weathers, just doing it, was inspiring". Mitchell and McCoig had been chosen to represent the department in the School's 3rd year trip to London, and they left Kintail, hitch-hiked to Fort William, walked from there to Ballachullish "carrying our boards and folios", and then managed to get a ride to Glasgow in time to meet up with the rest of the group, with Henry Hellier, Head of Interior Design in charge. They stayed in the National College of Rubber Technology Student Accommodation in Holloway, and Hellier steered them to where and what to see. "This trip really opened my eyes to all sorts, and it all happened over the Easter break".

McCoig followed Stewart's approach and work ethic in his own teaching. Throughout a long career, he's restlessly pushed himself and those around him to make things happen, but whereas Stewart often saw commercial opportunity, and responded to markets, McCoig does not appear to find money a motivator. What seems to stimulate Malcolm's creativity are the ideas themselves, and they're often quirky; sometimes transient, fleeting; sometimes fixtures of our world seen afresh. He's constantly alert to visual ideas and perspectives, but his pictures are seen through the prism of a dry wit, and then strong design structure, and a "whatever it takes" production approach.

Malcolm wasn't one of the students Tony Jones referred to, in not doing much textile design, he left GSA with a strong grounding in printing techniques, especially screen printing, but he was well grounded in textiles too. He’d been the only male student in the GSA embroidery class. However, when he arrived in Aberdeen in 1964, with his wife, Bel, (Note 3) to take up a lecturing job at Gray's aged 23, he was first and foremost a screen printer.

He was also a 'stayer'. The printed textiles department at Gray's had been run by two ex-Bob Stewart students, Peter Perritt (Note 4) and Hugh Barrett. Perritt had left to set up a department at Manchester University and Barrett had followed. They had close contact with Bob Stewart and his activities, with their students joining the Glaswegians for their Easter drawing trip to the West Coast in 1964 - while Malcolm was in his post-diploma year. Stewart told Malcolm that what Gray's needed was continuity. Too many people had been coming and going to establish a strong department. Malcolm was to be in post for over 30 years.

He developed skills as a teacher, too. The methods were based on Bob Stewart's. He used "virtually all of Bob's techniques and his ways of getting things out of people, but also the technical approach: I remember the Aberdeen students hadn't seen many prints being produced in-house before I came. In Glasgow you saw Philip Reeves working in the studio, and Bob Stewart too. They were teaching by example." Malcolm worked on prints regularly at lunch times. His teaching philosophy was "to get the students to find themselves. To get something out they didn't realise they had. We might have set the same brief, but we'd be determined to show that there was a different solution for every person in the studio, which could be coupled with technical capability. Bob Stewart always said it's good to have the creative coupled with the technical and also not to see it as a narrow specialism was important". Arthur Watson, who was a student at Gray’s from 1969-1973, remembers Malcolm as “an inspirational lecturer, who really didn't just talk about process, he talked about ideas and making work about things that you were interested in, that engaged you. Malcolm’s approach was – you do what you want and I’ll show you how to do it better” His Gray's colleague, Donald Addison, endorsed the approach: "Malcolm is a gifted, effective and enthusiastic teacher with an unusual ability to recognise and develop students' imaginative strengths and individual skills". His students got to have their own Easter drawing trip too, based at the Three Kings Inn, in Cullen, a hotel that was run by an artist, Alec Flett, who, to Malcolm's amazement, knew William Scott.

What drove Malcolm throughout his educational career was the need to help students to learn both how to improve their creativity and their technical skills. To this day, he's dismissive of the many drawing and painting art school departments where lecturers "cruised through on their reputations", although he and Bel have a special place in their minds for the renowned GSA drawing and painting tutors, Miss Alix Dick (Note 5) and Robert Sinclair Thomson (Note 6).

Let’s consider Malcolm’s pictures!

Detail from Moon Over Portlethen Bay

Malcolm McCoig's prints are often frozen visual instants. Snaps. If Malcolm sees it straight, he just communicates from eye to brain to paper; but he also sees things in upset and here the core idea is twisted; mis-translated; re-configured; there are blow ups and shrinkages; repetitions and reflections. Once the big picture is secured in his head and on the paper (it's nearly always paper), the process is about perfecting it, but with fun and inspiration (and what's available and to hand, in thought and resource). The end result always has clarity, the hook that all designers aim to place in their viewers’ minds. "Stop, what is this?", the image is saying, and then, Malcolm gives them fast flowing answers - bold blocks of colour, intellectual challenges, word games, throwaway ephemera. You can take a lot away in five seconds, an image that might stick with you, even though you may think it's not very substantive.

Here's "Digital Flats", a print from 1978. Hold your gaze beyond a few seconds, and you'll start to see that every window in this oblique tower block has a different colour and numerical message. Yes, there's an astragal across each, but there's a digital read out too, starting with number 0 and reaching a seventh floor. The horizontal divider is missing from only one black rectangle, on the ground floor, and that's the door. Is it a block of flats at night and a calculator or a digital message board? Every line is straight. Every in-filled square is textured graphically, and of course, they're not squares, they're parallelograms. I start to consider the painstaking work involved in producing this fanciful mirage. There's nothing instant about this work, and yet it's effect is fast and direct. The mind wonders what it's about: humans as digital read outs or individuals; black and white or variegated colours and patterns?

One can read what one wants, but my suspicion is that all Malcolm had in mind was to present the image, and his intrinsic fascination with technique and detail led him into layer after layer of additionality. Once he'd coloured the first window he was committed to them all, and once the second window was realised differently to the first, he had to do it throughout. Its the kind of engagement that makes a carpenter perfect a joint that will hardly ever be seen. Why do it? Malcolm is doing this for his own satisfaction, but also because he wants to offer the intense viewer something that rewards their engagement.

However, he’s not the kind of artist who adds references and footnotes to text to embellish limited substance. Where Malcolm appends narratives to his works in catalogues, he avoids suggestion of extra meanings. He usually offers an explanation of how the idea was sparked, or which techniques he applied.

Here's what he said in the catalogue about "Digital Flats": 'The flats are made from digital type units I had previously designed for a poster for an Aberdeen Arts Society Exhibition. I reduced the original unit and fitted 57 of them together into the desired construction. The digit screen was printed in two types of grey to give the illusion of depth and to indicate the numbering of each level."

Digital Flats

What Malcolm created is an image apart. Strong, direct, distinctive, and probably unique. Once the viewer has absorbed it, they might see tower blocks in a different way.

This print was chosen to be featured in a Scottish Arts Council touring exhibition, "Screenprinting" which toured to ten venues across Scotland from March 1980 to April 1981. Malcolm offered more detailed information in that catalogue, but it was all about technique (Note 7).

Through the late 70’s, Peacock Printmakers had created a new potential for painters to create multiples of their work, without understanding the printing techniques themselves. Experienced printers were available to translate their paintings for them. Malcolm generally turned down requests, but in 1981 he suggested turning one of Ian Fleming’s watercolours into a screenprint, and he documented the process – three weeks of work in the college’s holidays - on three pages of A4, notes he remembers sharing with Arthur Watson. They set out the creative and technical input he could make in screenprinting at the time.

Aberdeen Artists Society Exhibition Poster 1977

The result was “Preening Fantails”. Ian Fleming had made occasional input to colour decisions, but it was mostly Malcolm’s work. Ian Fleming signed the edition, of course.

MM notes on printing Ian Fleming’s Preening Fantails

Malcolm has created hundreds of prints on paper, and worked on textiles too: He created a big printed hanging (170" x 90") in four sections called “Chi-Rho” (after the Greek for the first two letters of Christ's name) for Aberdeen Royal Infirmary's chapel in 1988. It transformed the atmosphere in the room, creating a warmth and a sense of comfort, as well as creative interest, on a wall that hitherto had been white painted plasterboard. The way the thick curtain like material hangs is a key element of the visual experience. Malcolm’s "A Life In A Day": four triangular textiles on poles - sail-like - were produced for outside another Grampian health building, Roxburghe House.

Preening Fantails

Chi-Rho in situ at ARI Chapel

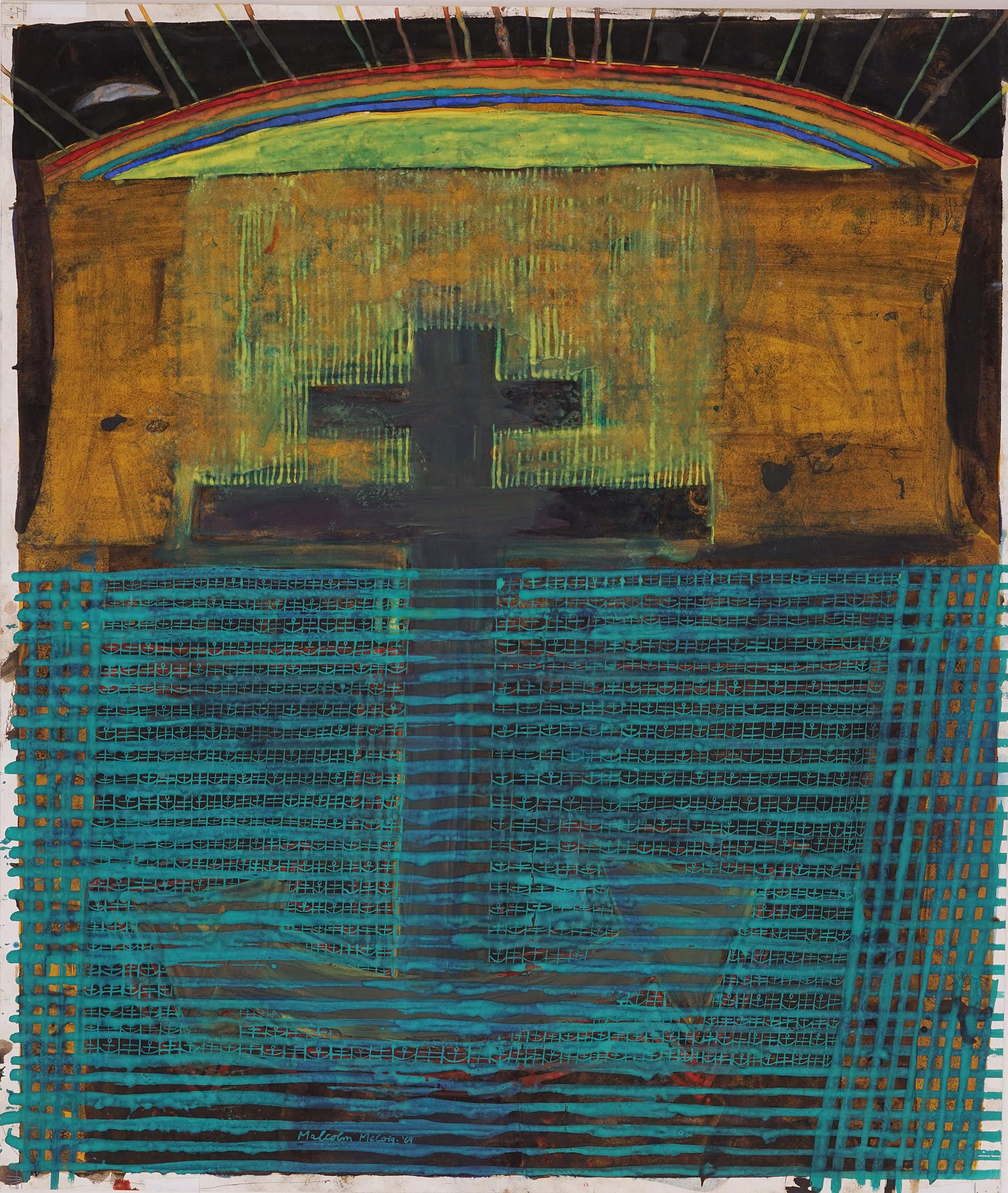

Malcolm’s paintings contain some of the instant ideas of the prints, but they're more likely rooted by motifs that have become themes. Some have started through commission: bridges, crosses; some arrive through everyday familiarity: dung heaps, fire smoke, drains, poles, nissen huts, vans and lorries. Malcolm likes shapes that can give structures to the picture design and focus for a viewer's eye.

At the intersection of design, print, and painting, all kinds of tools can be deployed to create the image, and one of the key distinctions of Malcolm’s art is the juxtaposition and integration of methods from each of these practices. He draws circles with compasses, straight lines with rulers, curved lines with flexible rulers. He can cut out shapes and stick pieces of coloured card on a surface that already contains multiple paint pigments, pencil, and ink. He can paint over stenciled textures to create a relief background to a wash. He calls them all paintings and they’re often mixed media, but not as most artists might use it.

In many of the paintings, a sheet of paper is usually encrusted with multiple layers of suspended pigment, sometimes, it seems, completely covering the sheet, enriching the colour scheme and the density of the picture's backcloth. Other times the layers are kept out of sections, or reduced in intensity to offer tonal gradation where appropriate. These backdrops might be painted and they could be printed. Then the fun starts. A large shape, perhaps a rectangle, circle, half-circle or cross, takes up position and establishes a central focus; or perhaps there's a grid of lines into which the same design, a variation, or a set of completely unique shapes are carefully placed.

That's how these pieces work. This is no free improvisation. This is all coolly calculated composition set out by a creative designer for the performer to follow, with sections allowing for extemporisation, but nothing that's going to shake the fundamental of the design.

As mentioned before, a very considered compositional process can be applied to a very mundane subject. The central theme might be a whim or a light-hearted joke. McCoig sees a world packed with tiny details of human frailties, involuntary mistakes, double standards, incongruous juxtapositions, and aesthetic misjudgements., and he takes inspiration from many. Then he asks himself to be playful and irreverent, and demands the viewer lightens up. But that doesn't mean he's telling you a quick joke or throwaway line. No, he wants you to remember this vignette.

The composition is central to the idea of the picture and it's in place from the start, but the structure can evolve as the work develops, with variations being assessed and counter-balanced, structurally and tonally. And when it's all starting to feel a bit solid or full-square, it might be time to introduce a disruptive, or a humorous element. Malcolm is always talking about “keeping it lively”. Where's that little cartoon pig sticker? I'll copy it in here. How about we make these Nissen-Huts be underwater? No-one's ever done that. And they haven't. I bet the only picture of an underwater Nissen-Hut in the entire history of art is the one realised by Malcolm McCoig.

The gestation of a picture can often take place within the wider thinking around a series of images that use the same concept. The print, "Digital Flats" was inspired by a graphic design that promoted an exhibition. The painting, "Jacob's Ladder" takes "Digital Flats" as its starting point. The block of flats is printed in the same central position in the picture, and at the same angle. The digital image now forms an outer decorative frame, where rectangles and squares are filled with paint gradations from safflower in the base through orange to primrose yellows and straw at the top. The numbers that are clearly read in the print, are less prominent. You can't make all of them out, and you wouldn't think about it if you didn't know the provenance. Instead of a grey wash backdrop, there is a repeated dot pattern printed in green across the entire picture, with an extra link to a sense of earth and sky through another background tint gradation - from white on what might be seen as a horizon, to dark grey at the top of the picture.

Submerged Nissen Hut

In Jacob's dream, the ladder ascended to heaven, but McCoig's angled block reaches a threatening dark grey tint with patterned green dots on top.

In the picture's world, the ladder has no rungs, and the digital block has been superimposed with a frantic, dark image, in which the central theme is a telegraph pole, cream out of black, festooned with warning lights, and spraying wires in multiple directions. It's painted on a mat of multiple pieces of cut card, applied with black wash, and decorated with a swirling pattern that suggests a celtic standing stone, and floral images, including a black tulip. There are no angels ascending or descending. Meanwhile, the wind must be blowing left to right, because the green tinted background has a scattering of bright coloured flotsam and jetsam, three pieces to the left and many multiples to the right, all of which are random shapes, apart from four white patterned butterflies.

It's a very striking image. Is there a meaning to it? Does it have to have one? Does God communicate through cables now? Malcolm's exhibition catalogue notes on this picture are blank. The shapes are the substance. There is strength and power in the ladder, and flimsy, ephemeral, unidentifiable and formless bits and pieces beyond. There is formality and abandon. Lines that can be drawn with rulers and others that can't. The half inch of solid grey at the picture's base with a darkened angled shadow under the angled block gives the picture an extra dimension feel, two to three, and adds an extra sense of empty space all around the central shape. However, there’s such a strong impression of 2D space-shape-space, that the base conversion isn’t enough. It’s a two-dimensional image set back a little! . And then you submit to space=shape=space.

It’s worth reminding ourselves that there is no distinction between space and shape in a patterned design on a carpet or a fabric. There are no meanings in textile designs. Just shapes and colours. The colours in Jacob's Ladder are just as important to the effect on the viewer as the shapes. Gradations of bright-to grey-green enclose a largely black and white image bordered by a decorator's palette of warm yellows and reds, and embellished with specks of turquoise, pink, brown, and green. The whole is underlined in two shades of grey, with Malcolm McCoig's pencil signature and '79' at the junction. In the catalogue, Malcolm calls it a painting. It is, but design and print are key to the way it looks.

In advance of this article’s publication, Malcolm has written an additional narrative on “Jacob’s Ladder”, and four other pictures. These are set out as an afterword to the text, after the Notes.

Jacob’s Ladder

Bob Stewart had recommended Malcolm McCoig to Gray's (Note 8), and he embraced his new environment with great positivity. Like Eardley and Morrison before him, the Clydesider's horizons were opened up by the big skies and away-from-it-all sense of the North East coast. Like Stewart, he printed, painted, and designed. He was known as a screen printer, because that was the new technique that he brought with him from Glasgow and he was its lead pioneer in the North East. Ian Fleming, one of Scotland’s foremost printmakers (and painters), was Head Of Gray’s, and he supported many leading practitioners within the teaching staff, all of whom were still based in the original Art School buildings in Schoolhill, next to Aberdeen Art Gallery. Malcolm’s immediate boss was George Mackie, Head of Design, who was renowned for his strong views, sometimes military-style approach, and excellence at stone litho printing. “One guy who I really liked was the flamboyant and opinionated Head of Sculpture, Leo Clegg, a Glaswegian, who was also the Coxwain of Aberdeen Lifeboat.” Malcolm always admired the Head of Jewellery, David Hodge, too: “his work was excellent”.

Moon Over Portlethen Bay

Across all Scottish art schools at the time, the design departments were always regarded as second class citizens by the painters, but Malcolm had a strong supporter in Ian Fleming. He established himself in the Aberdeen art world, and by 1968 he had a one-man exhibition at Aberdeen Arts Centre. Fleming called him an "original" and commented on how McCoig "derived his creativity from mundane things, suffused with a sensitivity well above the normal". How was he viewed by his peers? “As a printer, he was very skilled, incredibly skilled” said Arthur Watson, “One of the big shocks at Art School was the first time we went to see the Aberdeen Artists Exhibition in the Art Gallery, because then you got to see what all the staff did, and it very much coloured the ones you paid no attention to, and the ones you listened to (I know:it's terrible!)..Malcolm's stuff always really stood out.” In 1971 Malcolm was winning prizes at the Bradford International Print Biennale, and he had 17 screen prints and 11 paintings at a one-man show at the 57 Gallery in Edinburgh. He had another one-man exhibition at the Aberdeen Arts Centre in April 1973

Just looking at some of his output in 1972 is instructive. This was the year of the “Findon Flowers” print and "The Orders" suite of three prints on the Corinthian, Doric, and Ionian architectural orders. It was also the year in which he painted “Rainy Gourock” and “Suzie Wonders What It’s All About”. On a first look, they look quite distinctive – “Findon Flowers” leaning on a Bob Stewart inspired fabric-like floral design, whilst “Doric Poles” points to the austere and graphic in Malcolm’s creative mind, with the humourous tweak of turning the classical into the contemporary power supply. As in so much of Malcolm’s creative output, there are cross references (perhaps even straight lifts) from one work to another. The Findon Flowers reappear in “Rainy Gourock” with the design again strongly reliant on fabric-style repeat design, with extra added interest and humour via randomly placed, bright coloured small umbrella shapes in the right hand side of the banner. Then the Bob Stewart fabrics meet the poles and wires of “Doric Poles” in “Suzy Wonders..” (“A wee depiction of our first dog, who had the very distinctive feature of one ear up and the other down. It also features some of my first telegraph poles and pylons”). This is a strong reference point for Jacob’s Ladder, painted four years later.

The Plough

Findon Flowers

Rainy Gourock

Doric Poles

In 1974, it was Malcolm's support of his now former-student, Arthur Watson, and his enthusiasm and negotiation skills that helped to enable Peacock Printmakers to get off the ground in Aberdeen. He would subsequently be Chair of the organisation. For most artists across the North East, Peacock opened up print opportunities, but Malcolm was already fully immersed in the practice and since his move to Findon - on the coast south of Aberdeen - in 1970, he'd had a studio with printing facilities at home, as well as the facility at College.

Detail from Suzy Wonders

In 1975 and 1976 the UK Government bought McCoig prints for their Art Collection: "Scottish Interior (Horse and Plug)" ("one of the set of four which all fitted together into one big print") and "Doric Poles" (from "The Orders" suite)

In 1980, aged 39, he had a one man retrospective of prints and paintings from 1968-1979 at Aberdeen Art Gallery. The exhibition consisted of 87 items: prints, paintings, and greeting cards. Malcolm grouped the pictures chronologically and bracketed them descriptively with the dominant motifs attached to their period of employment. So "Sea and Moon" were 1968-1971, "Fabrics and Columns" were 1971-1976, "Pipelines and Telescopes" were 1974-1976, and "Words and Numbers" 1976-1979.

Scottish Interiors ( Full set)

Fog Horn

Ian Fleming wrote the catalogue foreword, pointing out that it was Malcolm’s "capacity to see, to stop and to wonder at some visual theme, no matter how unprepossessing and often passed over by others, which makes his work at all times exciting and worthwhile.. He can immerse himself by single-mindedness, akin to obsession, the sign of a dedicated artist, into a mundane subject and transform it into something rich and strange. Therein lies his originality... He is well balanced between the representational and complete abstraction, and not hesitating to accept each extreme, if it is relevant to his purpose. His technical expertise is there for all to see, and is always recognised as a means rather than an end in itself - he is too much the artist for that. Technique and vision have reached fulfilment in his work."

The exhibition was regarded as a success, and subsequently toured Scotland, including The McLean in Greenock

Partial Eclipse and Binoculars

Throughout the 70's and 80's his pictures were featured regularly at Aberdeen Artists Society and Peacock Printmakers exhibitions.

Malcolm spent three months in Madison, Wisconsin in the Autumn of 1982, in an artist in residence exchange with a US printer, Judith Uehling, who had been at Peacock Printmakers in the summer. The trip was funded by a Scottish Arts Council bursary, and greatly facilitated by Beth Fisher, who had studied there at the University of Wisconsin, and whose mother arranged accommodation for Malcolm. The trip stimulated a host of ideas, and a range of images made their way into prints. He visited print studios, workshops and exhibitions, and attended lectures. It was also an opportunity to reflect on the relative status, quality and resourcing of Scottish printmaking. He wrote in his report: "We are up to the best here in Scotland". He could also compare University teaching in the Printed Textiles department, with the Gray's approach: In Madison"Students appeared to have no real basic design training and when answering a simple problem, the images could range from portraits of Richard Nixon to blatant copies of Erte drawings".

Malcolm McCoig, c.1980

Garbage And Globes

Madison Aberdeen Connection

Sand

He was busy producing prints whilst there – he was given space in commercial studios- and completed five screenprints and multiple etchings. Simple, everyday American objects - buckets for sand and rubbish, basket ball boards - were framed into powerful images. Then, he worked on drawings and inspirations when he got back home to Findon and produced paintings and prints stimulated by the everyday observations that had lodged in his mind, his diary and his sketchbook. Symbols and signs, words and emblems fascinated and were often central to his creative work: in “Pitch In!” and “Sand” public receptacles for rubbish and winter road grit were turned into an overblown ironic flag-waving message and a twist on our established sense of “Sand” as the bin is caught in a snowstorm. “Garbage and Globes” incorporated Malcolm’s reflection that he felt battered by the letter W in Wisconsin , while down at the beach there was “No Lifeguard On Duty” – and the visual joke on the words needed no embellishment. "Madison Man", was a pair of human legs walking with a Madison city logo stuck where the upper torso and head might be. These pictures were exhibited at the University of Wisconsin and elsewhere in 1984, and in the big printmaking exhibition, “Britain Salutes New York”

On the American trip he also gave four lectures and a day-long practical workshop on his own techniques. Further short teaching missions followed. In 1988, the British Council asked him to go to the University of Nigeria, Nsukka, where the head of Fine Art had requested help with screenprinting. It was a bit of a frustrating experience: "I spent 2 weeks there adapting their primitive system into a workable state and getting students (who turned up erratically) to try all sorts of different stencils. They were to have a show of their work after I left, but I never heard if that happened. Money had been thrown at the department years before, but there was no real technical help to work and maintain the stuff. For example, a big process camera’s internal lens was covered with a very fine coating of desert sand, so all their exposures didn’t work."

American Garbage

Reprocess Orkney NO WAY (Dissolved Screen Print)

Reprocess Orkney NO WAY (Screenprint)

Orkney Return

More productively, he had a residency in Orkney in 1989, which produced two exhibitions, a joint one with fellow artist in residence, Alfons Bytautas, at the Pier Arts Centre in Stromness; and a solo exhibition at what had become known as Peacock Artspace in Aberdeen, in 1990: "An Orkney Diary". "Carefully composed, elaborately rendered, satisfyingly decorative images." said the Press and Journal. One of the images, a page from “An Orkney Diary” (one of sixteen prints in total), is hanging in Aberdeen Royal Infirmary today.

Malcolm had commenced an engagement with the Grampian Hospitals Art Trust in 1985 (it was Aberdeen Hospitals Art Project then). " Norman Mathieson, a surgeon, had been to Sweden, and he noticed that they'd got a lot of interesting art in the hospitals, and wondered whether we could do something here, but he didn't know how to go about it. I think it was Ian McKenzie Smith who suggested 'Why don't you get a group of art advisors, different disciplines, and see what they come up with. That's how it started. I was involved as an art advisor, just one of the guys putting ideas forward, talking about the space available and considerations like: will we have an exhibition gallery or something else? When Norman retired, I stepped into his shoes. Norman could be really difficult to deal with. I used to have fights with him, but I was the only guy that ever stood up to him. Being a surgeon, of course, he was used to having things his way. But I said, Norman, you're just a bloody surgeon, what do you know about it? You always had him that way! But I also even designed for the corridors, the wall colours and so on. The painters would say that was just decorator's stuff, but it was nice to do that too. "

Page from Orkney Diary

And then once we started putting things in, other folk would come and say what could they get from GHAT, and, of course, the Royal Infirmary Chapel was a bleak kind of place. The Reverend Alan Swinton said I'd like something for a wall, and so we wondered who would do it, and you don't want to put yourself forward, but someone said 'Oh, Malcolm he can do that. It's a fabric sort of job' ". This was the first of many commissions carried out for the organisation and turned into “Chi-Rho”, a large printed hanging in four sections. “I had the facilities and knew how to print all that stuff. I had the tables and I would do it over the summer. It was about a £1000 or something. It was peanuts for the amount of work you put in, but it was a nice job to do. And once I’d done that one, oh, they wanted more. This was followed by “The Four Evangelists”, a large circular screen print on the opposite wall from the “Chi-Rho”; and finally the 11 “Symbols of the Passion” linked both pieces by filling the whole back wall. Mind you, Norman Mathieson was keen on (getting involved). He would say 'I don't know if I like that bit or whatever', and I would say 'Oh Go Away'. Anyway one of the symbols of the passion was a lantern, and I thought it might be a nice idea to update it to have a nice torch, and he said 'Oh I don't know if I like that idea'. But when it came to the hands and the feet, I said 'Right, Norman', and drew around his hands, so his hands were up in there. That made him feel quite good. It was lovely to do the whole chapel."

Malcolm's international connections continued to grow when Eric Spiller, Head of Gray's, asked him if could take responsibility for promoting Scandinavian student exchanges. "I went to Norway, Sweden and Denmark promoting Grays – with quite a bit of success. Then a visiting staff member from Hame Polytechnic's Fredrika Wetterhoff Institure of Crafts – a very traditional weaving institute in Finland - invited me to come and do a course in more up-to-the-minute ideas and technical know-how. Speaking in English was a vital part of the course for the students, who, on the whole were excellent, but just needed a real confidence boost and a push into unknown territories. I got them to design stuff (mainly on big sheets of paper) that was, after two intense weeks, hung all round the college in specific sites. The staff couldn’t understand how we’d managed it, as their teaching was very traditional with traditional motifs. I did this for a few years (including after I'd left Grays) with a different set of design briefs each time. "

The Four Evangelists

In 1992, the McCoigs left Findon and the home studio and moved to Aberdeen's West End. In 1998 Malcolm proposed to GHAT that he produce a series of prints based on bridges over the Don and Dee. He made 90 unique hand painted prints! These were exhibited at the Royal Infirmary Gallery, and are still to be found across health establishments from Forres to Stonehaven.

Malcolm retired from his job at Gray's in 1996, and focused his creative time in his home studio, which was enhanced by a move to the country in 2000 - at Upper Coullie Farmhouse, near Auchenblae. The Nissen Hut next to the House became Bel's ceramic studio and its semi-circular shape became a new motif for many pictures. These were now mainly paintings, because Malcolm had decided to throw out all of the oil based inks he had (the printing industry was phasing out “unhealthy” inks and he didn’t like the alternative versions), and to focus on water-based work. The approach remained the same. Visual ideas from his everyday life, strong images, care and calculation, but there was more freedom of expression, and a greater subtlety in the colour schemes, taking advantage of watercolour.

His one-man exhibition in 2000, 'Greenock Revisited: An Exhibition Of Past and Present Work' was a timely return to his roots at a moment when his artistic practice was subtly changing: now focused on painting. The show reflected on nearly forty years of artistic development since Malcolm had lived in the town, but underlined how personally attached he remained. He brought motifs from across the years - ladders, crosses, circles, letters, signs - and cross pollinated them with the Greenock of his past and the Greenock as he found it at the Millennium.

A Bridge Too Far

Sunset Over The Clyde (Painting)

As if to underline the continuity in his work, "Sunset Over the Clyde" from 1963 was included, with its fundamentals reappearing in "Partial Eclipse, Dunoon" and the sun (or non-sun), becoming the focus of the "Lyle Hill Indicator" series. A strong central foreground image set against a belt of dark sea with distant lights on the far shore in Dunoon is a regular theme.

Sunset Over The Clyde (Print)

Cross of Lorraine, 1969

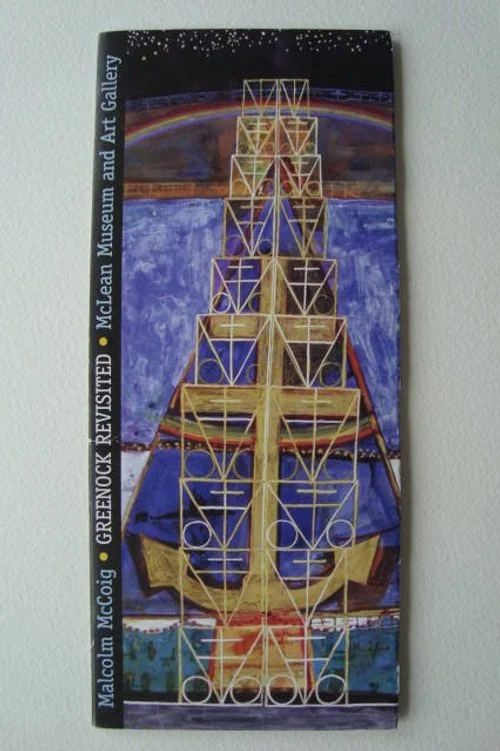

Cover of Greenock Revisited Exhibition brochure ft. Cross of Lorraine, 2000

Another re-appraisal of a 1960’s picture was “Cross Of Lorraine”. Malcolm had painted it originally in 1969, but returned to the powerful Greenock landmark for the new exhibition.

"Cross of Lorraine" and "Two Crosses" directly related to "Jacob's Ladder" and “Suzy Wonders..”, but used the powerful Greenock emblem of the Cross of Lorraine with an anchor at its base, well known as a memorial to WW2 French seamen, erected on top of Lyle Hill overlooking the town. In "Cross Of Lorraine”, it provided the fundamental structure to an overlaid scaffolding pattern using the symbol inside a box with two circles flanking the re-styled cross and anchor. This "ladder" disappears into a starry night sky above a broad full rainbow, with Dunoon lit and unlit across a silver or blue sea. In "Sunset Over The Clyde" yachts played around in the water. In Greenock Revisited, it’s nuclear submarines.

These Crosses pictures used the central image of a broad based shape at the base of the picture narrowing to vanishing point just short of the top of the picture, a path, a ladder, a set of steps... "Bubblyjock's Brae" (" a wee brae that we used to go up and down") offers just steps going up a hill, full width of the paper at the base, narrowing to a high point with a single figure at the sharp end.

Advert for Exhibition ft. Two Crosses

Greenoak Banner

"Greenoak Banner & Misty Town Hall" is genetically related to "Digital Flats", with the numerical digits replaced in yellow and orange squares by alternate oak tree and leaf symbols, shading dark to light from base to top. The squares are freely drawn within the ruled outline, the backdrop is dark and pale watery blues, manipulated into irregular streaks, behind which there's a ghostly textured shape of Greenock Town Hall. Loose, atmospheric, less serious. It's a big bold statement that the viewer will remember, but its not so earnest, and the double take is a much more whimsical joke. A Greenoak tower and "a big erection in the middle of town", which is it? For sure, Greenoak is a fake derivation, an anglicised etymology.

The Town Hall fun couldn't be restricted to one picture, and in "Comet Passing The Town Hall", the shape emerges from a grey blue gloom with a Comet shop sign overtaking its prominence. The Steamboat, PS Comet, provided the original passenger service from Glasgow to Greenock, and in 1962, Lithgows built a replica of the boat on its 150th anniversary. It would have been a memorable moment for a 21 year old. Word play, funny and clever commentary, translated into sketchy watercolour, from Malcolm's usual firm print statements. It's a much lighter touch than it would have been 10 years before, a snapshot, but observed with gentle irony. "This was a take-off of the original COMET passing down the Clyde and a comment on what's been done in that part of town"

"I went down to Greenock a few times. (The show) was divided into three sections: Past, Present, and Parents, so I'd taken stuff that my Dad had worked with in the shipyards, and some of my mother's things, like her apron and her bowling trophies. Then other things like the QE2. I'd done paintings of that, and then went back and saw other things." One of them was The Lyle Hill Indicator.

After the clever contrivances, Malcolm produced a lovely little set of decorated discs, poems set in pattern and colour harmonies. They are “4 Variations On The Lyle Hill Indicator” (Note 9).

Once the past and the present have been distilled, the show revealed another completely new side to Malcolm's output; and it was personal. No portraits, self portraits, or any human form, of course; but paintings that talk of Malcolm's relationship with his mother, father, and brothers that suggest a real sense of love and loss.

There was a diptych for Malcolm’s brothers, John and Robert (Note 10), based around the marvellous cast iron work of the Greenock Cemetery railings. “Robert was an international badminton player, and he asked me to design a logo for his company “ShuttleBob”, so there's shuttlecocks all around, and my other brother was a welder so there’s all sorts of wee secrets for him. My twin died aged 40, and my fit brother died aged 61”.

Comet Passing The Town Hall

Then there were his father’s mementos from his lifelong career in the shipyards. A series of pictures using shipbuilding templates moves from classic McCoig structures to dream-like abstractions. “Templates(Submerged)” is a pale watercolour where thin washes of grey and pale yellow pigment are formed into the template shapes that his father had around the house and used in his work to produce the appropriate curves and bends that shipbuilding design required. They float abstractly in a sea of warm pinks and oranges with a faint horizon and tiny sun spotted centrally. It’s a long way from Malcolm’s strong foregrounded images, hard edges, and firm lines. Knowing the shapes’ contexts, it hints of love and warmth, water and horizons beyond. “My father was a loftsman. A very skilled job where he (and others) drew out the structure of the ship full size on a huge loft floor, cut out templates of wood which were then passed on to the guys who then used these templates as guides to cut out the actual ship’s metal structure. The wee templates I used in the work were specialised curves that my father had for all the tricky bends and shapes. As a family, we burned many thin left-over templates for kindling. I thought these wee offcuts were fascinating, as they were covered with letters and numbers and instruction for the platers.”

There was also a long piece based on Malcolm’s father’s note books: “I found a lovely wee book, after he died, of all the ships he'd worked on in Scott's…he worked there for fifty years almost, and he'd a lovely wee diary with all these lists, and I printed it out into a huge piece and gave it to the Museum as well, so folk could go in and say "Oh remember such and such", and the wartime work and all that.”. The piece also includes an ink sketch of his father.

Cemetery Gate

Perhaps the most delicate and poignant picture Malcolm has produced – at least, from all of the ones I’ve seen – “Pairs Winner 1964” – also stands out from his traditional approach by having no internal framing, central image, joke, none of the standard motifs, themes or threads… It’s a picture of almost translucent white flowers in bloom, placed against a backdrop of olive and yellow-green foliage. It looks like a printed textile, but there are no patterns, no repeats. On close scrutiny there are two small badges featuring saltires, and on even closer scrutiny, there is some pale lettering arranged across a flower-head: WOSW. There’s a clue! West of Scotland Women’s. The BA for Bowling Association is missing, but the badges are presumably awarded by the WOSWBA . Malcolm explained that this was “Mother’s bathroom curtain, with appliqued “winners” badges. The flowers are metamorphosing into badges too”. Templates and patterned fabrics express deep affection for departed parents, and carry a stronger emotional power because they shed all of the stylistic body armour that Malcolm had developed over the years.

"Greenock Revisited" presaged a substantial five artist show ("From A Distance") which Malcolm helped to organise at the McLean Gallery in 2002. Bel exhibited alongside other Greenock artists from their generation, including Mike McDonnell , Ron Sandford, Alex Gourlay, and Ian Campbell (who contributed by sending pictures from Australia). They had all known each other from GSA days. Campbell and Sandford had shared a student flat which Malcolm moved into, and later Malcolm had a flat in Kelvingrove Street with McDonnell and Campbell, and then Gourlay. Here was an illuminating display of Greenock wit, grit, talent, determination, fancy, and playfulness - active and dynamic creativity and technique from a group of artists in their early sixties.

It's not possible to be in Malcolm's company for very long without one or more of these Greenock personalities coming into conversation. None of them stayed in Greenock after school, and none of them had straightforward artist careers, but their lives continued to intertwine, and their ongoing artistic endeavours seemed to provide constant navigational checks for Malcolm. McDonnell's retirement from medical practice in 2000 and Sandford's from design, architecture and commercial drawing in 2002, seemed to unleash an outpouring of artistic brilliance - both based in Yell, Shetland.

Pairs Winner 1964

In 2004, it was time for another Malcolm McCoig solo exhibition outing. There was a pile of new material: "Dungheaps and Other Crap" which was hung at the Royal Infirmary Gallery in Aberdeen. It was too much of an opportunity for McCoig, living in their midst. Twenty seven pictures were produced on the subject. Publicity seeking? It got him a TV feature on the BBC's farming programme. Malcolm obviously enjoyed his interview with the Aberdeen Evening Express: "People won't be wrong if they call it a pile of crap. I did it because I got so fed up with the seriousness of art".

In 2008 the horizons of the subject matter had broadened and the levity was less to the fore. Malcolm gathered together a collection of paintings that perhaps declared a greater ease with the world, reflecting the pleasures of being in the Mearns. He presented them in a solo show appropriately at the Meffan Gallery, in Forfar, which he called "No Smoke Without Fire". It featured strong images, based on totemic shapes of the deep-rooted Mearns farming culture: lots of Nissen Huts, smoke streaming in the wind, fires consuming waste... His former colleague from GHAT, Jane Kidd, wrote a revealing critique, which I hope she doesn't mind me quoting because it sums up McCoig's subject focus in the middle of his Upper Coullie painting period:

"McCoig's new work is partly a personal response to the ever-changing Howe of the Mearns farmland where he lives, and partly a record of the ceaseless human activity which allows the famous agricultural terrain to thrive.

Malcolm McCoig is primarily interested in the patterns of the world, both in the way shapes echo each other in the landscape - whether they are formed by smoke columns from field fires, or the swooping curves of irrigating water jets. The scattered pattern of a heap of discarded grow-bags echoes the shape of a heap of snow, and the rim of the sun repeats the shape of the ever present Nissen Hut. Despite his love of colour and pattern, Malcolm resists the more obvious charms of the Mearns, confining the rich colourful patchwork of fields to a walk-on part as the view glimpsed from the doorway of a shed interior, where the real work goes on.

Detail from Rusty Tank And Dung Heap

Nowhere in this group of work is the human form seen, although human activity is the chief point of the interest in the wider landscape and Malcolm McCoig's ever present dry wit is engaged by the way humans unwittingly contribute visual piquancy - the white contrails of two jets soaring in the blue sky and the logo of a humble Portaloo both proclaim our national identity, sublime and ridiculous.

Wit and visual interest are brought together in the recurring motif of the Nissen Hut, which becomes a thing of fantasy - appearing some 25 times in this exhibition. It's a plaything, a backdrop, and a large curving absence, or its practical elegance is expressed as an imaginary flat-pack whose two dimensional curves remind us incidentally, of technical drawings for shipbuilding – reflecting McCoig's own roots on the banks of the Clyde.”

In Malcolm’s new world, we still have bold images and instant imprint, but standing in the centre of the exhibition, the design of each picture could be lost in the overall effect of colour harmonies. The 35 pictures, all landscape and of the same size, formed a set of chromatic harmony changes that fitted together into a coherent composition where each individual component complemented and played against its relations. Blues with greens; pinks, mauves, and subdued reds with greys and pale blues. Colours and shapes, but colours beginning to become more important.

Moonlit Unlit Bonfire And Portaloo

Ineffectual Scarecrow

Eduardo’s Scarecrow

Mearns Landscape With Bales

New Kid On The Block

Scarecrow with Full Moon And Sunrise

Malcolm moved to Edzell, over the border in Angus, in 2018 and has set up a studio upstairs under the roof eaves. Picture ideas keep coming. He talks of being freer with his approach. Painting with less calculation. His first focus was a series of paintings based on the old road sign that stands before the arched entrance to the town on the way in from Brechin. Here he employed a graphic designer's creative conceptual approach to explode the sign's shape and letters into an extraordinary set of theme and variations, colourful, playful, and as ever, focused on strong image making, careful calculation in the design, but a less formal rendering. They look like the work of an artist who is challenged and excited by his work, and passionate enough to want to keep exploiting the theme with ever more adventurous ideas.

Scarecrow With Full Moon

Cloudy Edzell With Sunset

Currently there are multiple studies and preparatory sketches around the walls, working on two themes: the 20-20 oblong discs painted in the Edzell roads to test speed, and a pile of soil worked into abstract imagery by criss-crossing tractor tyre-marks. He misses the pressures of exhibition deadlines, but he's still ready with an eye for turning the every-day into art, and finding the time for experiment and play.

Whatever he does with the lines, shapes and colours still waiting for their moment, Malcolm McCoig's singular approach will infuse them with that special tone that he’s seemingly carried for sixty years since it emerged under the influence of Galt, Greenock, and Bob Stewart’s GSA in the 1960’s. It’s an eye that sees where the ordinary meets the odd and the quirky; where the ephemeral can be made firm, and vice versa; where patterns and coincidences can be filtered and processed. In this creative world, shapes can be given extraordinary strength or made limp; and everything is fixed by compositional calculation, technical capability learned from years of practice and experiment, and an expertise in colour harmonisation. Malcolm might scoff and say - don’t analyse it too much: It’s only a picture.

Sleepy Edzell

Note 1: Alexander M Galt, 1913-2000, was born in Greenock, and grew up in humble surrounds. He went to Glasgow School of Art in 1930, and won a Carnegie Scholarship to Paris in 1938, staying in Montparnasse. His "Stable Boy" oil was bought by the McLean Gallery in the 1930's. Malcolm McCoig recalls with amazement how he could draw extraordinarily effectively and quickly in chalk on the school blackboard. Galt later became the President of the McLean Gallery and was instrumental in buying many of its best paintings, including work of the Colourists. Malcolm didn't realise the regard that people had for him until after he died. There was a retrospective of his work at the Mclean in 2003.

Note 2: As quoted in Robert Stewart Design 1946-95, ed.Liz Arthur, p.1/2.

Note 3: Malcolm and Isobel McCoig (nee Mowat) were married in Gourock, Bel’s home town, in July 1964, having met at GSA . Bel studied drawing and painting.

Note 4: Peter Perritt

Like Robert Stewart, Perritt combined his academic activities with a successful commercial design career. He designed geometric patterned fabrics for Heals and other companies in the mid-60's that were very popular and influential. The V&A holds a number of examples. Perritt and his wife returned to North East Scotland later in life to own and run a hotel (The Bayview) in Cullen, which featured fabrics and carpets of Perritt's design, before retiring to Southern Spain. Bel and Malcolm McCoig considered buying The Bayview at a later point in its life, but settled for a cottage in the Seatown area of Cullen.

Note 5: Alix Dick

Jessie Alexandra Dick, 1896- 1976, was on the staff at GSA from 1921-1959, and for the last twenty years, Lecturer in Drawing and Painting. Drawing was her speciality.

Note 6: Robert Sinclair Thomson,

Sinclair, 1915-1983, replaced Alix Dick at the end of Malcolm's first year at GSA. He had a military air about him, and a distinctive presence because of his peg leg prosthetic. Despite this, he was a very active man: a motorcyclist, fisherman, canoeist; and quite charismatic. His second wife, Barbara, had been a Dior Model. Joan Eardley was a regular social visitor in the 50's and posed for him.

Note 7: Excerpt from Screenprinting Exhibition Catalogue, 1980, p. 28

Malcolm McCoig

Digital Flats

Edition of 12

1978

Printed and published by the artist

at 3 Coastguard Houses, Findon (own studio)

on Curwen Standard Mouldmade paper

Paper 57 x 77.5 cm

Image 49.5 x 71cm

One handpainted separation (outside rectangle) and 2 photographic separations (57 digital units and a selection of Letraset textures) giving three direct stencils. These were altered by hand with screenfiller for the many background blocks of colour, the baseline and shadow

90T and 110T Polyester Monofilament screens

17 Colours, oil based ink

The graded sky area was printed by pouring different colours onto the screen and blending them with the squeegee. Several rough proofs have to be printed and discarded before regular prints are obtained. This is commonly known as rainbow inking or split fount.

"The flats were made up from digital-type units which I had previously designed for a poster advertising the Aberdeen Arts Society Exhibition 1977. There seemed to be a rash of digital watches about at the time. I reduced the original unit in size and fitted 57 together into the final sloping construction. The graded sky and very low horizon line was to accentuate the height of the flats. Each floor level is indicated numerically by varying the position of the greys within the digits. The textures were printed through a slightly finer mesh (110T). The dark entrance and shadow were printed last to try and give added depth"

Note 8: Bob Stewart's reference for Malcolm McCoig said:

"Malcolm McCoig's standard of design is incredibly high. He's extremely hard working and diligent and his integrity is beyond question."

Note 9: The Lyle Hill Indicator series comprised four paintings of the circular disc in different colour palettes and settings. You might call them “The Four Seasons”. Alongside the Cross of Lorraine on the top of Lyle Hill above Greenock, there is a marvellous 360 degree viewpoint with a table d’orientation pointing out hills, islands, and other landmarks. “Every time I tried to draw it, it was always covered in globules of rain – so instead of fighting it, I just went with it”. The new world of Malcolm McCoig’s paintings was abstracting, loosening up, working without commentary. Malcolm does not have any images of the Lyle Hill Indicator, nor does he have a record of who bought the pictures. If anyone reading this has access to any of the four paintings and would be happy to share an image or let us take a photograph, please contact art-scot

Note 10: Bob McCoig (1937-1998) was described in 2022 by Badminton Scotland as “Scotland’s greatest ever badminton player”. He won the Scottish National singles title fifteen times; won the US open twice, and the Canadian open, both in doubles; and he won medals at the Commonwealth Games and the European Championships.

A.

Here’s Malcolm’s own commentary – from June 2022 – on “Jacob’s Ladder” and four other pictures, which are presented alongside.

Jacob’s Ladder: The basic format is using a version of the original screen print but with no patterns on the “windows” – just painted grading colours from very pale yellow down to orange/red. Stuck over this is a cut-out print of part of “Findon Flowers” on dark coloured paper (the original print was for a coloured paper commission, shown in Dusseldorf) with additional painting and one of my telegraph poles. “Splodges” on the right hand side were little trial colour prints before using them on the final “DF” print. There are five wee shapes which were stuck on pieces of paper – some ripped off, some not.

Jacob’s Ladder

The whole picture was screen printed over with dots from the “Fog Horn” print – they could have been printed twice? (white then green) Hand painted dots were put in the “windows”. Lastly, wee butterflies were painted on other smudges. It just felt the right thing to do, but I remembered that the paper company, Samuel Jones of Tillicoultry who commissioned the original “Findon Flowers” had a butterfly as their logo and one also appears in that print

I have always liked this piece – quite elegant and soft compared with the harsh original “DF” print

Five Dice And Four Ladders

Five Dice & Four Ladders, Three Dice on a Ladder: These two “dice” pictures are spin-offs from the Symbols of the Passion commission, using the main motifs of Dice, Ladders & Crown of Thorns. The cruciform one is one of the three basic shapes I used in “S of the P” and the other, has a circular feel which was another of the basic shapes. “5 Dice” is quite dense in colour while “3 Dice” is light and airy. In the commission there are only three dice, but 5 fitted in well with the cruciform shape. At the time of painting (1996) my house roof was being fixed and they were called “N E Slating Company”, so that went in too. The intertwining C of T in “5” change tone from two thirds dark to one third light and a white light bursts through the top making the shape hot quite so rigid. Varying white dots enliven the edges, but not all edges. Coloured parallel lines also subtly enliven the dark background.

“3 Dice” plays with the optical and transparent possibilities of the cubes and they fit into the rungs just fine. The round “sponge on a stick” contrasts with the cuboids and is the only solid white. The C of T are doubled up – single tone and a neutral wash fills the background but allowing the watercolour to settle into naturally random forms to keep up the interest. The brave random shapes in the centre are completely meaningless as I was using a new type of pen which happened to leave silver centres and a blue edge when drawn on to wet paper – otherwise it can all be too predictable.

Both paintings are square and “5 Dice” frame is the actual format used in the commission.

Three Dice On A Ladder

Festive Barrier with Deer and Pig: This painting (one of a series) did not start life as a commission or graphic etc. At the bottom of my farm track there was a new ditch going in, so a collection of these red and white barriers were put round it for safety. Then I started noticing these barriers everywhere – round pot-holes, digging up streets etc. I drew one out fairly accurately and then just started kicking the idea about and putting them into different situations. I also enjoyed linking them together (which they do anyhow) and created more patterns from them. I also did a series of small ones with only one barrier each in different positions.

This one was one of the last and is very dense compared with the previous ones. Simply divided by a sloping edge, the barrier is very dark with the, what should be three fluorescent shapes, being collaged on in three slightly varying tones. There is another smaller, even darker barrier lying on the slope and there are hints of others creeping in too. The deer and pig were paper constructions I had lying about, so I just put them in. (I used the deer in my Christmas card, and as I had just installed solar panels, I put those on the side of the deer so his antlers were lit with brightly coloured bulbs)

The deer and pig gave the picture a “running” feel to it and the different coloured circles/spots followed that “wheel” and moving idea. The colours took a long time to get just right. The last brave gesture was to take a scraper with some transparent white on it and just go round the barrier, hopefully creating some more movement and not wrecking all the previous work?

Festive Barrier With Deer And Pig

Rusty Tank and Dung Heap: I saw this big rusty tank sitting on its breezeblock plinth every day as it was at the edge of the steadings where I had to pass to go in or out. I liked the patterns and dribbly rust patches along with the tube which showed the level of whatever was in the tank (it never had anything in it)

The long line of dung in front wasn’t there but came from another farm (Pitnamoon) but I just stuck it in. I’d seen air fresheners inside a tractor’s cab, which I thought was quite funny, so I just used them (two basic designs) in many paintings, so I thought I’d just place two on the plinth – one full view, one hiding.

I’d unsuccessfully tried several backgrounds, but finally came up with a tracing taken from the actual cracked earth (very dry summer) as a strong contrast with the tank, but still acknowledging the similarity of the rusty shapes. The background is real Howe o’ the Mearns earth, mixed with PVA to bind it together – so the colour and stuff, is the real deal.

Rusty Tank And Dung Heap

Three Dice, or, a wee Tribute to Bob Stewart: The dice are inside a chalice with the ladder and sponge on a stick forming an X. The C of T is quite quiet, but the thorns are a bit “bloody” in bits. The structure is basically a white blobby centre on a dark, uneven background. The pattern on one of Bob Stewart’s jars is rolled out to fill the whole of the base, anchoring the whole picture

B.

Another aspect of Malcolm’s humour- and constant clever calculation – is found in some of the pricing of his pictures. You could purchase his " 5 Dice and 4 Ladders" - carefully stencilled with 'NE Slating Co' down the ladders' outer edges, not for £220 or £225, but for £222, a message from the angels of course! It's the hint that leads you to read the picture not in terms of decay and everyday in the countryside with thorned briar stems entwined through the ladders, rather than snakes; but into exploring the symbols of the Passion - the arms of the Cross, with ladders, dice, and a crown of thorns. It’s an echo of the subtle messaging of a Renaissance artist to humour the intellect of their religious patrons.

C.

"Rainy Gourock" (1972) was decribed by Malcolm in an article he wrote for the Aberdeen Arts and Entertainments Guide, 27, April 16-30, 1973, which coincided with his exhibition, Malcolm McCoig: Screen Prints and Paintings at the Aberdeen Arts Centre Gallery.

Here's what he said:

""Rainy Gourock is so complex in construction that I even forget how some of it was achieved. It involves poster paint, emulsion, ink, coloured paper, dye, collaged pieces of my own screen prints, ball-point pen, silk screen filler etc. I think I sometimes work this way to give me a sense of 'the sky is the limit' and all these bits and pieces help me not to feel restricted. It might still be a very simple image-idea I am trying to solve, but all these surfaces and goings on hold my interest at a distance of, say, twenty feet and also at two inches ! This particular picture took at least two months to complete, working on it most nights and weekends."

D.

Many thanks to Viki McDonnell, who has sent us a picture from the Lyle Hill Indicator series - see Note 9 above. Here it is:

Three Dice, or A Wee Tribute To Bob Stewart

All of the photographs are by Stuart Johnstone, who retains the copyright, with the exception of Submerged Nissen Hut, Detail from Suzy Wonders, A Bridge Too Far, Cover of Greenock Revisited Exhibition brochure ft. Cross of Lorraine, 2000, Advert for Exhibition ft. Two Crosses.