Pierre Lavalle: Art as Life

In June 2023, Nicolls Gallery, Glasgow, presented an exhibition of paintings by Pierre Lavalle (1918-2002). Organised by the artist’s daughter, Cherie, the show placed Lavalle’s work on public view for the first time in a generation, showcasing the art of a fabulously original, now largely-forgotten creative force in Glasgow’s post-war art scene.

The exhibition came as something of a bolt from the blue: quite apart from the fact that the show (the first in 33 years) did not coincide with a particular anniversary or occasion, the work on display reflected a singular talent which has been almost completely overlooked in the current literature on Scottish art.

Douglas Erskine’s comprehensive critical biography situates Lavalle in the post-war Scottish art context, considering his exhibiting, lecturing and writing activity as well as his art practice. It hopes to establish a mature introduction to Lavalle’s life in art.

Lavalle c.1970s. Photographer unknown.

Pierre Lavalle was born Arthur Noel Lavalle in Sunbury-on-Thames, Surrey, in 1918. The son of a Belgian mechanic who arrived in Britain as a refugee at the beginning of the First World War and a district nurse from Berwick-upon-Tweed, Lavalle spent his childhood in the south of England and in the Scottish Borders, where Presbyterianism exerted a great influence on his young mind. In 1929, the economic depression prompted the Lavalle family to emigrate to France, where Monsieur Lavalle found work in Valenciennes, an industrial centre close to the Belgian border. Lavalle’s education in the commune of Anzin appears to have instilled or at least encouraged an active interest in visual art, although he is not known to have received any formal artistic training outside of conventional schooling [1]. A developing practical interest in painting, which bred the uninspired, all-too-ordinary landscapes which Lavalle would later describe as “rotten paintings”, appears to have evolved slowly in the shadow of his political and intellectual activity. His staunch association with leftist political groups, particularly the Valenciennes anarchists, supported his concern for the social and intellectual advancement of the working man. The anarchists’ progressive, even unorthodox views on art stimulated thought about the nature of visual art and its role in modern society [2].

The threat of the impending war brought Lavalle back to Britain in 1938, alone, where he settled in London. Although a pacifist, Lavalle’s anti-Fascist beliefs were surely crucial in his decision to join the British army on the outbreak of war. His fluency in French earned him a position in the Defence Ministry, where he worked until 1945; other positions in the civil service followed, first in the Ministry of Information then in the Charities Commission. Lavalle’s marriage to a well-known professional violinist introduced him to many of the leading artistic and literary figures of the day: he socialised and discussed art with Lucien Freud, Dylan Thomas, Herbert Read, Ethel Mannin and others in well-known pubs like The Wheatsheaf [3]. Arthur Lavalle took pride in his continental roots and delighted quite publicly in his status as an outsider; Ethel Mannin’s nickname “Pierre” stuck.

As he approached his thirtieth year, Pierre Lavalle’s artistic pedigree amounted almost to null. Unlike many of his contemporaries who were pursuing painting careers, Lavalle had no formal art qualifications, no exhibiting experience, and had produced only a small body of work of questionable quality [4]. But even as a young civil servant in London, the qualities which would propel his existence as an artist now appear pre-determined and clear. An earnest engagement in leftist politics reflects his intellectual curiosity, conviction and enthusiasm, further borne out in what we know of his spirited quarrels with Fitzrovia’s finest in The Wheatsheaf. By the end of the war, Lavalle’s artistic ability may not have been fully fledged, but the image of a vigorous, confident and curious young man with serious ideas about art suggested his career in the Charities Commission would be short-lived.

In 1947, Lavalle was recently divorced, long-bored of civil service work; steeped, by now, in the motions of practicing and thinking about art, he was also entertaining an ambition to break out of the capital and forge a living as a professional artist. The city still known then as “The Second City of the Empire” exerted a particular attraction to the would-be painter. Glasgow had survived the Blitz relatively unscathed compared to London and a wartime revival of industrial power signalled a welcome sense of confidence and identity in its citizens. Gritty, romantic stories of the Gorbals and Red Clydeside piqued Lavalle’s interest, perhaps fed to him by his Wheatsheaf friends, many of whom had strong connections to the broadcasting world which at that time owed a great deal to Glasgow’s BBC base. The effect of the Second World War electrified Glasgow’s artistic scene, establishing a singularly attractive, stimulating centre for modernist creativity. The acclaimed colourist J.D Fergusson and pioneer of modern dance Margaret Morris – a partnership of artistic giants, forced from France – settled in Glasgow and established the New Art Club, an informal exhibiting and discussion society which drew together young progressives. Influential Polish artists Jankel Adler and Josef Herman, also displaced from Europe, imparted an inspiring contemporary central European flavour to Glasgow’s art culture. For Lavalle, a place within Glasgow’s vibrant artistic community may have suggested an opportunity to settle into his Celtic roots without compromising his strongly-felt continental sensibilities: in the Glasgow of the 1940s, there was little chance of slipping into a parochial stupor. The political dimension of Glasgow’s cultural scene, which extended to exciting developments in letters and the performing arts, must also have exerted an attraction: Unity Theatre, established in 1941, was a democratically-run, anti-fascist theatre group which relied on the support of many visual artists in order to fulfil its aim of highlighting working-class issues before working-class audiences. Edinburgh may still have dominated Scotland’s arts climate, and Glasgow’s artistic establishment held sway in the city, but for Lavalle, the appeal of Glasgow’s dynamic, politically-engaged artistic underbelly must have appeared irresistible [5].

Lavalle with early abstract paintings in an unidentified exhibition, probably sometime in the early 1950s. Photographer unknown.

Lavalle’s ambition to break out as a self-taught professional artist in Glasgow reflects a remarkably strong sense of confidence and self-belief. As welcoming as Glasgow’s arts scene may have appeared, Lavalle seems to have had no working knowledge of the city’s formal and informal artistic networks prior to settling in the city in 1947, let alone the security of a teaching position (a necessary source of income for most artists in Glasgow). Over the course of the next 25 years of uninterrupted artistic activity in the city, Lavalle trod a path fraught with artistic, financial and personal challenges, and found his reward chiefly in the recognition afforded to him by his reputation as a sincere, original, modern painter of the weird, the wonderful and the beautiful; his gifts as a lecturer and a writer established his name as an authority on Scottish art, driven to promote contemporary work before as broad an audience as possible. His remarkable self-belief and the qualities of determination and endurance which mark his artistic existence in the face of a climate which was not always sympathetic to his work – or indeed to the visual arts in general – demands respect. Lavalle’s relationship with Glasgow is difficult to establish and his comments, made over a long period, tend to contradict themselves: he would emphasise the city’s beauty and take pride in its history and culture; then again, he would state that Glasgow’s beauty was to be found in its inherent ugliness; he even described Glasgow as “the world’s dirtiest city”. Lavalle’s opinion of Glasgow shifted over the course of many years, but his enduring attachment to the city and his efforts in celebrating its cultural life reflect a deeply-felt love.

From a base in a studio on Glasgow’s Sauchiehall Street, Lavalle cultivated fruitful and lasting artistic relationships through formal circles and informal meetings. Association with a community of like-minded artists was crucial in Glasgow, where the progressive artistic scene, though fertile, was small and the commercial art infrastructure even smaller: private galleries favoured the establishment figures who taught at the School of Art or who held membership to the Glasgow Art Club, while municipal galleries showed no local work as a matter of policy. Fergusson’s New Art Club, which prized individuality of approach, welcomed Lavalle to its bosom with regular meetings and exhibiting opportunities in mixed group shows. He found kindred spirits in the Glasgow painters Bet Low, Tom MacDonald and William Senior, who stood somewhat apart from the core of the Club as self-proclaimed anti-academic “Independents”. Gifted, inventive and each driven by sincere political conviction, the trio had established the Clyde Group in 1946, explicit in its aim to take art to the working people of Glasgow. This unquestionably stoked the political flame which burned bright in Lavalle, and he exhibited with Low, MacDonald and Senior several times over the course of the coming decade. Lavalle did not come to Glasgow to bury himself, as he put it: his painting and exhibiting practice reflect a desire to reach out to others in collaboration and connection [6]. Outside of galleries, meeting rooms and clubs, Lavalle became a “weel-kent face” among the students and creatives who frequented Sauchiehall Street’s cafés and pubs. An enthusiastic and indefatigable conversationalist, his younger friend Alasdair Gray remembered that Lavalle revelled in artistic discussion, always more interested in learning about the work of others than in speaking about his own [7].

Lavalle (right) with Luigi Marzaroli, c.1951, probably in Casa d’Italia, Glasgow. The photographer is unknown but it is likely to have been Luigi’s brother, Oscar, the celebrated photographer.

While association with the progressive young artists loosely centred on the New Art Club provided certain exhibiting opportunities in the later 1940s, Lavalle gained broader public recognition through his contributions to a significant number of shows in the 1950s. By the time of his first recorded outing in 1950, Glasgow’s art economy had slumped into austerity. Commercial galleries had dwindled even further since Lavalle’s arrival in the city and the vibrant, experimental climate of the early-to-mid 1940s had become a memory far removed from the daily reality of most practicing artists [8]. Self-promotion, independent of the support of a dealer or gallery, was the order of the day. Solo exhibitions for any artist who stood outside the establishment were costly, risky and therefore rare: for instance, Lavalle’s great friend Donald Bain had sold work to the value of £140 in a self-mounted 1953 one-man exhibition – a significant sum – but admitted that his expenses far exceeded his takings. Lavalle found a valuable lifeline in preparing and contributing to medium-to-large scale mixed group exhibitions in Glasgow, Edinburgh and London, often alongside his “Independent” Clyde Group friends. Exhibiting with others, even alongside only one other artist in a two-man show, meant that costs could be shared and better sales achieved through the increased chance of good publicity. Lavalle was one of some 15 artists to contribute to the memorable, widely publicised open-air exhibitions hung on the railings of Glasgow’s Botanic Gardens in 1956: the innovation of presenting work to ordinary people in an anti-establishment gesture, outside the gallery, was rewarded by an overwhelmingly positive public response. Inside the gallery, several of Lavalle’s shows were evidently quite esteemed affairs: in 1953, exhibitions which included Lavalle’s work were opened by such distinguished guests as the preeminent actor Duncan Macrae and the Edinburgh art doyenne Anne Redpath [9]. Other presentations were decidedly more rough-and-ready: during the Edinburgh Festival of 1953, Lavalle and Smeaton Russell hastily persuaded the Oxford Theatre Group to share the premises they had rented on Riddle’s Court, and so an exhibition of the paintings which the artists had ferried to Edinburgh that morning on a wing and a prayer accompanied a production of Strindberg’s Miss Julie. Lavalle’s proactivity and opportunism, all-important in an unforgiving climate, ensured that by 1956, as noted in The Observer, he was “no stranger to the viewing public”.

By the end of the decade, Lavalle also had three significant one-man exhibitions under his belt: no small feat for an emerging artist in 1950s Glasgow, deprived of the support of a dealer, a teaching position or the steady patronage of wealthy friends and family. The first exhibition was mounted in Sauchiehall Street’s McLellan Galleries, one of very few reputable venues which now and again played host to exhibitions of local, contemporary work. Lavalle hired a portion of the Galleries in February 1954 and presented an exhibition of recent paintings, completed and framed in a studio which had become a casualty of the hiring fee: the financial burden of the exhibition meant that the studio’s gas and electricity were cut off and Lavalle was almost evicted (“a painter in Scotland has to be able to do his own framing and it’s not easy working in the dark”, he commented wryly) [10]. A further, smaller show, “I Give You Sunshine and Rain”, was staged at the premises of the British Council on West George Street in August that same year. A residential scholarship at Cercle Culturelle de Royaumont, an independent cultural institution near Paris, followed in 1955; after a period of three months and the creation of some 50 paintings, Lavalle was awarded a solo show at Galerie Ray, Paris. The critical response to these exhibitions was almost as mixed as the nature of the work on view: the exhibitions comprised abstracts, sombre portrait studies, bright landscapes, fantastical and sometimes troubling religious anecdote, even a seascape created from shells, a cleaver and two pieces of firewood. For instance, the works included in the British Council show were described by The Herald’s critic as garish, crude and “extravagantly undisciplined”, while Jack House in The Evening News praised Lavalle’s painterly virility, reporting that his works supplied a series of “artistic punches in the eye”. Reviews from the period summon an image of a singular, zealous artistic character, rendered all the more eccentric for his European heritage. The cuttings do not, however, volunteer the image of an artist on the brink of riches.

Urban Landscape - c.1960s - gouache on paper - dimensions unknown - private collection.

Reproduced with kind permission of Henry Gibbons-Guy.

An image of urban Glasgow.

For all of the artistic gratification that was undoubtedly part and parcel of each exhibition, Lavalle’s industriousness often appears to suggest a struggle to stay afloat. The financial demands of marriage (Lavalle found a wife in Helen Marguerite Watson in 1948) and the birth of a daughter (Cherie, Lavalle’s only child, was born in 1955) presented pressures which could not easily be alleviated by the rewards of his exhibiting activity, although he made ends meet through adequate sales. By the time of his McLellan Galleries show in 1954, Lavalle estimated he had sold around 140 pictures during his time in Glasgow. He had attracted a modest following in the city, listing a hotel proprietor and an architect among his collectors [11]. The BBC had also bought a picture as early as 1950 [12]. Contacts in the French Institute, Edinburgh, were helpful in generating clients: their influence appears to have assisted in the sale of a painting to Jean Masson, the well-known French writer and director, who intended to commission a tapestry based on the work from the legendary Jean Lurcat [13]. But sales were too infrequent to provide a dependable, healthy source of income. For all of the expense of the McLellan Galleries venture (to name but one exhibition), Lavalle had sold only seven works. Driven by his belief that the success of an exhibition could not merely be accounted for in terms of sales – in a 1954 cutting, Lavalle commented with pride that “Glasgow is beginning to understand abstracts” – he was not easily deterred. The passion he had demonstrated in painting and mounting exhibitions throughout the decade, well documented in the press, marked him out as an ideal candidate for pastures new.

In 1957, a new educational scheme presented Lavalle with an opportunity to express his noted enthusiasm for art in a new direction in return for a stable, competitive wage. Martin Baillie was familiar with Lavalle’s work as a painter with some modest lecturing experience in his capacity as art critic for The Herald newspaper; he also headed Glasgow University’s Extra-Mural Department. Baillie employed Lavalle to work as a part-time travelling lecturer in a forward-thinking government scheme designed to boost public art education. Lavalle and other artists including Tom MacDonald, Alasdair Gray and Alasdair Taylor – all of whom had cultivated highly individual styles which were rejected by the establishment - were paid a regular salary to prepare and deliver colour-slide presentations across the west of Scotland, typically in small towns without galleries or other resources to foster engagement with art [14]. Between 1957 and 1970, Lavalle offered evening lectures in Campbeltown, Dalbeattie, Dunoon, Lochgilphead, Oban and elsewhere, often in venues such as high schools and colleges. His lecture series’ - each of which typically comprised ten or twenty individual lectures - were wide-ranging: “Modern Scottish Art” provided an introduction to Scottish visual culture from MacTaggart to the Young Glasgow Group of the 1950s and 60s; “The Art of the Renaissance in Italy” and “Baroque and Rococo” offered insight into the great historical periods; “Contemporary Art” addressed the myriad styles and movements between Post-Impressionism and late Picasso. For Lavalle, lecturing may have been a godsend: obvious financial benefits aside, the initiative allowed him to give form to the vast reserves of art historical and theoretical knowledge he had cultivated since his formative years and to engage with intimate, genuinely interested audiences who valued his insight. That these audiences were chiefly composed (as Alasdair Gray remembered) of housewives and pensioners presented an opportunity to honour the democratic, art-for-all philosophy which he had held dear since his association with the Valenciennes anarchists; far from the studios of his “Independent” friends and the coffee shops of Sauchiehall Street, brimming with bright art students, Lavalle provided professional tutelage to an underrepresented demographic for the fee of only £1 per 20 meetings [15]. He later reflected on the value of the Extra-Mural lectures: the innovative colour-slide format and the employment of practicing artists, chosen more for their promise than their establishment connections, did a great deal to lift art out of dull academicism and introduced “a more stimulating, yet at the same time scholarly, form of lecture”. In “Art Appreciation: Evolution of Art Forms”, a series delivered in Ayr in 1959 and 1960, Lavalle promised to divulge the mystery of his hero, Paul Klee: in his advertised aim of imparting weighty, modern theories about art to his students by relying on a broad, basic art-historical context, his eagerness to engage with others is clear; his approach is respectful and un-snobbish, appealing to the intellect of his audience without neglecting their novice status. During Lavalle’s years as an art missionary, Martin Baillie was richly rewarded for his faith.

Untitled (Dream Landscape) - c.1960s - gouache on paper - dimensions unknown - private collection. Reproduced with kind permission of Henry Gibbons-Guy.

A highly decorative imagined landscape.

In 1962, Lavalle’s association with Glasgow University, coupled with a steadily growing public reputation gained through continued exhibiting, led to a meaningful if relatively short-lived relationship with Scottish Field, then branded “Scotland’s greatest magazine”. The contents of the monthly Scottish interest publication were wide-ranging, and by the early 1960s sometime contributions from distinguished arts figures including Tom Honeyman and Douglas Percy Bliss accounted for much of its visual art content [16]. While Edward Gage wrote on art for The Scotsman, and Martin Baillie and Cordelia Oliver for The Herald, Scottish Field had no art critic until its editor, Sydney Harrison, turned to Lavalle. A new monthly feature, “New Scots”, aimed to offer insight into contemporary Scottish culture by introducing a cross-section of fresh faces in poetry, prose fiction and art. Literary contributors were many: William Price Turner and Norman MacCaig were among those who submitted items to the poetry feature [17]. By contrast, Lavalle was the only consistent voice of the art column over the course of New Scots’ duration from April 1962 to March 1964.

The aim of New Scots, Harrison explained, was to shed light on the lives and works of Scotland’s emerging creatives, and the challenges that faced them; it was a hearteningly broad scope which offered Lavalle the freedom to promote, on his own terms, the ideas he held most deeply and the Scottish art he most admired. In the past, installed in New Art Club’s circle, Lavalle had sought to promote the art being produced around him: he had opened exhibitions of his contemporaries’ works, attended dinners and given speeches [18]. In his lectures, he did not neglect an opportunity to promote the work being produced around him: in “Art Appreciation: Twenty Twentieth Century Artists”, Lavalle discussed the work of contemporary Scottish artists such as William Crosbie, Tom MacDonald and Anne Redpath alongside Braque, Munch and Kandinsky, on the basis that all pioneered “new ideas and new forms in paint”. In Scottish Field, Lavalle used his monthly column to review exhibitions, introduce new talents and dig deep into established names, often with reference to a theme or idea which he was eager to expound before an audience. Although his contributions were published on a monthly basis, as opposed to the weekly columns of his contemporaries writing for the broadsheets, Lavalle was offered greater space than Baillie, Gage or Oliver, and enjoyed an important added benefit: he could rely on the lavishly-illustrated Scottish Field to reproduce as many as four or five images alongside his text, often in full colour [19]. The result was the creation of a series of articles which now read as an evolving alternative survey of mid-century art in Scotland, and in particular of painting in Glasgow.

Lavalle’s first New Scots article, published in April 1962, does not read as a fledgling debut: it appears as a fully-formed, mature piece of criticism which, considered alongside his later Scottish Field contributions, stands up as surprisingly typical. In his first column, as in many of his subsequent texts, Lavalle chooses to write on two young Glasgow painters personally known to him, reproducing examples of their works as well as portrait photographs, and explaining the value of their efforts in relation to important twentieth century concerns and themes. This first article, concerning Douglas Abercrombie and Carole Gibbons, establishes the strength of the formula. Lavalle places the artists in a clear and compelling intellectual, art-historical context, in this instance discussing the death of academic art in Europe and the emergence of new values which bred a climate in which decorative but audacious works of art can be prized. It is a device which successfully marks Abercrombie and Gibbons out in their field, stressing their significance as fine artists in a European tradition, not just a Scottish one. He offers a brief, literal description of each work in the image caption: of Abercrombie’s “Sea Front”, he writes simply “this is a collage, and pieces of paper, bus tickets, etc, are arranged to suggest a seafront” [20]. This refreshingly unpretentious addition is a reminder of Lavalle’s commitment to educating the would-be enthusiast, no matter the extent of their art vocabulary. But Lavalle is at his most memorable in writing beautifully and unintrusively about Gibbons’ angst-rich painting, “Man in the Moonlight”: “I find something uneasy stirring at the borders of the mind; an unknown quality, something akin to fear, something that agnostic man has locked up in a box” [21]. It is one of many wonderfully vital insights to be found spread across 24 Scottish Field articles, in which Lavalle’s incisive critical mind, enviable command of language and humane, supportive role as publicist was offered before a large, broad readership.

Lavalle’s two-year spell as a regular contributor to Scottish Field confirmed beyond doubt his status as a leading authority on Scottish art. From what little evidence is available to gauge the public reception to his writing, the response appears have been very positive [22]. Correspondence with the artists discussed in his articles reveals their gratitude and praise: David Donaldson thanked Lavalle upon the publication of a piece devoted to his work in November 1963, noting that “most people tend to [try and] see the point of what I try to do: you don’t”. Lavalle’s writing was not commended across the board, however: T. Elder Dickson, the Vice-Principal of Edinburgh College of Art, took exception to Lavalle’s obituary of the Edinburgh painter John Maxwell, and his sentiments were published in Scottish Field’s letters section. But the magazine was clearly favourable to Lavalle, commissioning six articles on subjects including Fergusson and the matter of art therapy over and above his regular New Scots contributions over the course of his association with the magazine. The reason behind the end of Lavalle’s relationship with Scottish Field is unclear; his March 1964 column on E.A. Hornel was to be his last. Thereafter, following a gap of five months in which no regular art feature was published, the critic Emilio Coia took Lavalle’s place.

A typical page from Lavalle’s New Scots column in Scottish Field, dating to September 1962, concerning the painters Fred Pollock and John Taylor.

Reproduced with kind permission of Scottish Field.

It is a challenge to comment on the value of these Scottish Field articles with authority. Alasdair Gray wrote that “if a history of Glasgow art is ever written, the author will find Pierre’s ‘Field’ articles the best single guide to the 60s” [23]. While they will unquestionably provide significant insight to any historian of the period, their standing as a compelling, watertight survey is of course hindered by the absolute diversity of names discussed: Eardley and Gillies are discussed in the same breath as now virtually unknown painters such as Alfredo Avella and Anita Rushbrook. While these articles are generally enriched by the writer’s proximity to the subject, they are occasionally compromised by his tendency to be overly generous in the promotion of his friend’s work: in November 1962, Lavalle related Tom MacDonald’s painting to that of Cezanne and Rembrandt, writing “I have no doubt whatsoever that Tom MacDonald’s work contains a certain touch of genius and that he will become one of Britain’s better-known artists” [24]. Lavalle is at his best in writing poetically and sincerely about an artist’s work, but often, unfortunately, he does not provide much more than an introduction to each name: the reader will typically find around four-fifths of a given article devoted to a lengthy, sometimes playful preamble in which Lavalle meditates on a notion that should account for little more than an introduction. But if the twenty-first century reader cannot rely on Lavalle’s Scottish Field articles to provide a consistent, comprehensive survey of the Scottish art of the day, then one can certainly expect to find an insightful and often beautifully written introduction to the spirit of the times.

Lavalle’s Scottish Field articles signal something of his importance as a serious creative force in post-war Glasgow, but they also offer valuable insights which allow for an enriched understanding of his own visual art. Across his columns, he articulates some of the passions, tastes and beliefs which nourished and directed his art practice. There is value to be found in mining Lavalle’s articles for insight into his painting since his body of work can appear somewhat forbidding, for all of its visual directness. Its variety certainly caused unease in critics: a single exhibition of Lavalle’s work dating to the 1950s, 60s or even 70s could comprise a dizzying array of imagery which could leave visitors feeling bewildered. Many of Lavalle’s images appear deeply bizarre, even shocking: a gouache on paper created sometime in the 1960s, for example, depicts a mythical, ogre-like being in possession of an enormous erect phallus, seeming to menace a procession of little deities or spirits sliding down an umbilical-like chute. But even critics like Jack House, who once compared an early show of Lavalle’s paintings to the sight of “a lot of carpet patterns”, could not deny the power of Lavalle’s work in pleasing the eye, stimulating the brain and stirring the imagination. From his “rotten” early landscapes, through experimentation with abstraction and figuration in the 1950s, towards the distillation of his vision into jewel-like icons in the 1960s and 70s, some of the key points in Lavalle’s artistic course can be plotted through his own words.

Untitled (Mythic Scene) - c.1960s - gouache on paper - dimensions unknown - private collection.

Reproduced with kind permission of Henry Gibbons-Guy.

A strikingly bizarre, even disquieting image, possibly depicting Pan.

Lavalle’s articles reveal his faith in a number of the intellectual currents which shaped the art of the twentieth century. He dwells on the significance of Dadaism in his writing and indeed his lecturing; much of Lavalle’s work is rooted in the spirit of this movement, which sought to turn the Western art tradition on its head in the aftermath of the First World War [25]. His images of the carnival – a recurring theme in Dada – and his remodelling of authority figures like policemen, who are recast to appear close to the figure of Mr Punch, have a sardonic edge and an innate ridiculousness which undermines the values of traditional painting and cuts to the core of twentieth century art concerns. For all of Lavalle’s genuine delight in whimsy and visual humour, much of his painting can be aligned to the work of those advanced European artists who were seeking a new idiom to adequately express the ridiculousness of a broken modern world.

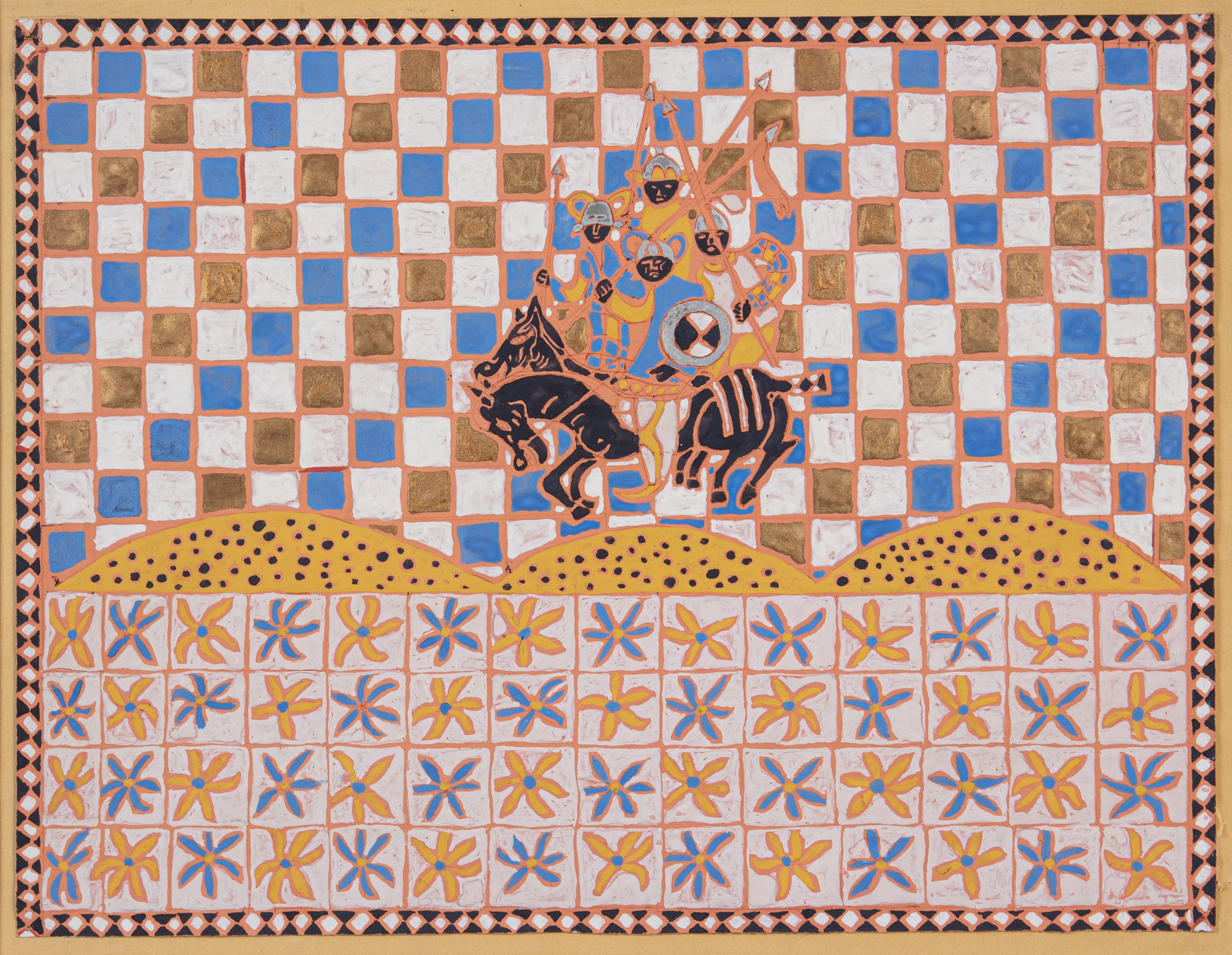

Persian Warriors - c.1960s - gouache on paper - c. 30 x 20 cm - private collection.

A richly decorative image which reflects the visual culture of the Middle East.

Clearly discernible influences drawn from a general understanding of Central African tribal culture reflect Lavalle’s interest in “primitivism”, a philosophy devoted to the emulation of non-Western cultures. Lavalle was an enthusiastic proponent of the theories associated with this intellectual and artistic movement, which gained momentum among modern artists of the twentieth century who, like the Dadaists, had lost faith in the Western art tradition: “an element of the primitive [is] essential to a good artist”, he commented in Scottish Field [26]. In their stridently anti-naturalistic imagery and searing colours, many of Lavalle’s most memorable works appear to owe a debt to the power and directness of African art; some, like “Mask”, appear specifically related to the customs and rituals of tribal culture. Painted on a piece of shaped hardboard with a handle-like protrusion which seems to invite its use in fancy dress, Mask possesses Lavalle’s playful humour in abundance, and no small flavour of the Dada carnivalesque. At first glance, it might appear to flirt dangerously with crude pastiche of African culture. But it is in fact quite a mature artwork which reflects a sincere homage to the broad intellectual climate of “primitivism”, which extended beyond a concern with African culture. In Mask, miniscule gem-like shards of colour bring to mind the mosaics of the Byzantine world which Lavalle so admired; obsessive surface decoration, underpinned by a pleasing internal order, also reflects his keen interest in the art of the Middle East. This work shows evidence of Lavalle mining the imagery of different historic and non-Western cultures for inspiration; in Mask, we find these wide-ranging influences presented with confidence and intuition. Although his work does indeed owe a debt to a certain intellectual climate, works like Mask show Lavalle’s ability to successfully assimilate a cocktail of influences to create playful and unpretentious work of original visual substance.

Mask - c.1970s - enamel on board - c. 20 x 20 cm - private collection.

A playful work which nevertheless reflects an interest in primitivism and wide-ranging cultural knowledge.

Lavalle’s brilliantly fertile imagination was chief among his gifts. It is true that his work stems from serious thinking about art and from a broad range of artistic influences, including Klee, Kandinsky, Matisse and even Rouault. In the way Lavalle absorbed, melded and expressed these influences, his works rarely show signs of effete or clinical conception. But his best images have a captivating freshness which seems to have been carried magically from the imagination straight onto the paper or the board. Lavalle’s 1961 painting, “Baboon with Umbrella”, comes to mind: while the image might conceivably have been informed by an African folk tale, this hardly accounts for the large parasol in the creature’s right hand or the smiling, moon-like face which grasps the end of its tail like a snake’s rattle. The bizarre whimsy of Baboon with Umbrella should lurk somewhere deep in the subconscious, but in this striking, richly decorative image, the creature appears to leap out of the imagination to assume a real presence which is almost nightmarish: its inscrutable expression, rendered in a haze of broken diamonds and lozenge forms, pulls the viewer into an uncomfortable dialogue with all the hypnotic power of a kaleidoscope. The unforgettable images which Lavalle conjures from the depths of his imagination stir something in our subconscious: to quote the artist himself, the viewer might sense something stirring at the borders of the mind; that unknown quality akin to fear.

Religious Scene - c.1960s - enamel on board - 20 x 20 cm - private collection.

A scene from a religious story realised with child-like clarity.

A supreme imagemaker, Lavalle’s least-innocent works stand up as among the most effective and memorable in his oeuvre. Unsettling images created around the same time as Baboon with Umbrella, such as “Decapitated Head”, are treated with a comparable boldness of form and strength of colour and decoration. This disarming approach is further demonstrated in a number of disquieting religious and moral works from the 1960s and 70s. In these little pictures, the strange ambivalence of Lavalle’s child-like vision – not to say his execution, which is highly controlled – renders the horror of a surreal hellscape or an episode from the Agony in the Garden, showing Christ laid helpless in Gethsemane, all the more haunting. His depictions of even the most horrific events are stripped back so dramatically – there are no curling fingers or bloodied torsos in a Lavalle crucifixion – as to achieve a basic pictorial truth which stays with us. In his first Scottish Field article, Lavalle had praised Douglas Abercrombie and Carole Gibbons for striving towards the role of image-maker, as opposed to supplier of decoration: Lavalle’s religious works show him fulfilling the same role, demonstrating that a domestically-sized, figurative-narrative painting on a traditional theme can burn itself into the mind of the contemporary viewer. Many of his finest religious works have the quality of modern icons.

Saint - c.1960s - enamel on board - 20 x 20 cm - private collection.

An iconic depiction of a saintly figure, possibly Mary, Mother of Jesus.

Lavalle’s gifts as an imagemaker might be particularly noticeable in works which have a disturbing edge, but within the broad spectrum of his output, such works occupy a relatively small place; the majority of his most mature images concern the beauty and serenity of the landscape. Lavalle had been creating fine landscape work since the time of his earliest exhibitions in Glasgow, using oils to present imagined vistas, sometimes populated with strange Bosch-like demons [27]. In 1959, a three-month spell as voluntary warden at North Strome Youth Hostel in the western Highlands marked the beginning of Lavalle’s earnest investigation into pure landscape. Fascinated by the play of light across Loch Carron, Lavalle’s observations of real-life phenomena melded with his knowledge of Optical Art and he proceeded to slowly abandon a tried-and-tested method of achieving both form and decoration in his pictures: while he had, up until that point, relied on a motif of repeated triangles, diamonds and lozenge shapes, Lavalle’s time in the Highlands prompted him to experiment with a more organic, less formulaic approach. His more mature images of the waters of Loch Carron remain highly patterned, but for all of Lavalle’s pictorial inventiveness, they also appear surprisingly faithful to a given scene: in “Black Mountain”, irregular shards of brilliant colour hug one another, seeming to rise into peaks then dip into troughs in a pleasing description of choppy waters. A similar treatment bleeds into many works of the mid-to-late 1960s and is particularly notable in Lavalle’s images of decaying industrial Glasgow, but is at its most sincerely-felt and successful when incorporated into his landscapes.

Black Mountain - c.1960s - enamel on board - 20 x 20 cm - private collection.

A typical image of Loch Carron, featuring a mature and pleasing treatment of choppy waters.

Lavalle’s lucid, concentrated images of Loch Carron have a wonderful decorative appeal which aims to impart visual pleasure to the viewer. The beauty and seeming simplicity of Lavalle’s pictures have a deceptive function: in an age when the potency of the visual medium has been compromised, the brilliant strength of Lavalle’s images do something to attest to its power. A Lavalle landscape might find its way onto the wall of a Glasgow drawing room because it appears to summarise landscape: in offering the city-dweller a view of sea, sky, trees, hills and mountains, one of Lavalle’s brightly-coloured, domestically-sized and relatively affordable paintings may appear to have it all. Perhaps surprisingly, Lavalle’s images are informed by actuality. From certain vantage points around Loch Carron, Lavalle came to appreciate the wholeness of the landscape: far from industrial Glasgow, he found he could admire woodland, mountains, sea and sky in one gulp. He noted the connectedness of this pocket of the world, observing how the waterways had shaped the geology of the land. Upon returning to Glasgow, Lavalle sought to sum up the essence of the Highland world in terms of a painted microcosm. We find the landscape of Loch Carron distilled to its essential elements, captured and contained as only an artist knows how: Lavalle draws the elements together on a miniature scale; he eschews any perspectival depth; he dreams up a raucous palette; he installs his image within a tight decorative border. By celebrating the decorative potential of his medium so openly, while remaining faithful to the beauty of a real-life scene, Lavalle created a series of images which stand alone as totally unlike any other iteration of the Scottish landscape genre.

Yellow Mountain - c.1960s - enamel on board - 20 x 20 cm - private collection.

A typical landscape inspired by the scenery of Loch Carron.

By the 1970s, Lavalle’s art had evolved to a point of remarkable refinement. From the extravagance and fierce colouring of early abstracts, his most mature paintings have a concentrated visual power which attests to the importance of the medium. Lavalle’s work from the 1970s was largely landscape, but he sustained a broad range of interests: the catalogue from a 1975 exhibition lists works such as “King”, “Dance” and “Black Angel” alongside various images of the Scottish Highlands. Highly idiosyncratic works dating from roughly this time such as “Anger” - a grotesque head study, intricately decorated with a constellation of minute spots which almost suggest beads of sweat forming over an infuriated, gurning face - prove that Lavalle was not prepared to settle into a formula: his imaginative faculties were undiminished and his work is always rich in the element of surprise. But diverse as Lavalle’s work may have been, his favoured method of painting directly onto unprimed, standard-sized domestic tiles (usually made from hardboard) with enamel paint had the satisfying effect of relating the works exhibited in a given show into an apparently unified body. If the works from the 1970s represent Lavalle’s finest achievements in their quite consistently refined visual impact, this is not to suggest that the work he produced in the 1950s and 60s was necessarily inchoate. It does, however, help to illustrate an interesting direction in Lavalle’s art. The gradual refinement of Lavalle’s work can be aligned to specific events such as his spell in the Highlands, but it might also owe a debt to his engagement in writing and lecturing: each activity established an outlet which allowed Lavalle to express enthusiasm for particular periods, styles and approaches. The fact that his visual art appears to stray away from the influence of Paul Klee – noted by critics around the mid-1950s – as and when Lavalle was given opportunities to write and lecture on the work of his hero, may not be coincidental: perhaps writing and lecturing satisfied his urge to produce an essay on Klee in paint. The suggestion that Lavalle’s artistic energy was so great that it could only be disciplined if an urge was satisfied in some other way – by a different facet of that same passion, so to speak – supports our understanding of Lavalle as an artist of near-boundless enthusiasm and curiosity. The nature and trajectory of Lavalle’s visual art practice, in all of its richness and originality, may therefore go hand-in-hand with his other art activities. For Lavalle, all of his efforts were inextricably connected: they sum up the man himself.

Anger - c.1970s - enamel on board - 20 x 20 cm - private collection.

A strikingly idiosyncratic head study; evidence of a fertile imagination.

Throughout the 1960s and 70s, Lavalle presented his mature works in a series of significant exhibitions in respected venues across Scotland and further afield. In 1968, he showcased a large number of his Loch Carron landscapes for the first time in a second solo exhibition in the McLellan Galleries, supported by a Scottish Arts Council bursary [28]. The Traverse Theatre Art Gallery in Edinburgh presented another solo show of Lavalle’s work the following year. An enthusiastic Canadian admirer, who came upon Lavalle’s work on a visit to the Edinburgh Festival, arranged to exhibit 30 of his recent paintings at the Confederation Art Gallery and Museum, Prince Edward Island. This show, comprising landscapes, religious subjects and pieces of what Lavalle described as “fantastic realism” (surely a catch-all term for all things deliciously idiosyncratic), travelled to various other venues in Canada’s Maritime Provinces, including St Mary’s Art Gallery. Lavalle also enjoyed a fruitful relationship with the North Briton Gallery, based in the village of Gartocharn by Loch Lomond. The “NB’s” director, Bill Williams, proved to be an enthusiastic supporter of Lavalle’s, staging three successful solo exhibitions of his work in the early-to-mid 1970s; the final exhibition in 1975 yielded sales amounting to as much as £660. But in spite of some successes, the returns of Lavalle’s later exhibiting career did not quite add up. Perhaps because his work was always priced quite modestly, or that solo exhibitions incurred greater costs, or that involvement in group exhibitions was more difficult to come by as time passed - the result of the breakdown of an artistic network he once valued – Lavalle struggled to make ends meet, even while living a quiet life in a small room-and-kitchen flat in Maryhill [29]. The contents of a letter to Maurice Miller, MP for Glasgow Kelvingrove, lay bare his frustration: Lavalle asks, “is it not strange that here am I, considered by the University of Glasgow and other organisations as an authority on art, yet can get so little reward for myself?”

Christ and His Disciples in London - 1975 - gouache on paper - c. 30 x 20 cm - private collection.

Courtesy of Great Western Auctions.

Lavalle fuses his interests in religious anecdote and the industrial cityscape.

Lavalle also faced considerable personal challenges in the late 1960s and early 1970s. A period of ill-health culminated in a serious mental breakdown and his subsequent hospitalisation in 1971. The cause of this crisis is not exactly known, and it appears he was able to continue painting, albeit slowly, in its wake. Lavalle experienced further trials in the early 1970s, with the breakdown of his marriage and the vandalisation of his studio. That the salvaged works were presented in the NB Gallery’s 1975 exhibition demonstrates a strong resolve on Lavalle’s part, as well as the praiseworthy efforts of Williams and his team. The NB Gallery hoped that their exhibition, together with the effect of a simultaneous show of Lavalle’s work at the English-Speaking Union of the Commonwealth in Edinburgh, would establish his name as a leading figure in Glasgow’s post-war art scene before a new generation. But in 1976, a sudden cessation of all art activity on Lavalle’s part did something to prove that his own personal determination, suddenly lost, had been the chief driving force behind his continued activity and public reputation. While the exact reason for the effective end of Lavalle’s artistic life is unclear, Alasdair Gray’s estimation undoubtedly comes close to the truth: “he was suddenly exhausted and depressed by continual exile, by his artistic and spiritual generosity which too many people ignored or thought merely comic” [30].

The information which exists on Lavalle between the age of 58 years old and the end of his life is very slim. The quiet life he lived in Maryhill was punctuated in 1990 by a large-scale exhibition, organised by his friend Brian Petherbridge and his ex-wife Margaurite, whose lasting friendship he greatly valued even after the end of their marriage. The Scottish Arts Council awarded funding for a retrospective of Lavalle’s paintings from 1947 to 1975 at the Pearce Institute, a cultural centre in Govan, to coincide with Glasgow’s year as European City of Culture. The successful exhibition did something valuable to stoke the flame of Lavalle’s memory: many works sold and an attractive though small catalogue, featuring an excellent essay by the now-acclaimed Alasdair Gray, offered insight into his life in art and hinted at a legacy. The exhibition introduced a vital, unforgettable body of work to a new audience. As the Pearce Institute noted, “these post-war years have been described as a time of inertia in the visual arts in Scotland; visitors can confirm there was no inertia on Lavalle’s part”. The most tangible result of the exhibition might have been its effect in stimulating Lavalle’s return to painting: in the final few years of his life, he took renewed pleasure in creating art. Lavalle died of pneumonia at Glasgow's Stobhill hospital on 22nd March 2002, aged 84 [31].

Lavalle as an older man, aged 72, around the time of his retrospective exhibition at the Pearce Institute.

The story of art in post-war Scotland comprises a cast of thousands: of these, few characters have achieved the recognition they deserve. Anyone who cares to scratch the surface of the accepted narrative will find an army of talent standing to attention. Lavalle is an artist whose gifts, it would appear, are yet to be discovered by this century’s Scottish art audience, let alone understood or celebrated. That he could have largely disappeared from view in spite of his numerous and significant contributions to Scotland’s cultural life is tragic; that he could have been so personally demoralised by the tepid response to his blazingly original artistic practice is doubly depressing. But that Lavalle produced such a fabulous body of work and that he endeavoured to share his enthusiasm so passionately, in the face of certain triumphs and many challenges, is quite a poignant reflection of the strength of the human spirit. It is ultimately a measure of Lavalle’s belief in the power and importance of art. For him, “fine art was worth making, whoever ignored it” [32]; for him, art might as well have been life.

Douglas Erskine

Appendix A: Biography

1918: Born in Sunbury-on-Thames, Surrey, the son of a Belgian mechanic and a Scottish nurse. He has one sister, Jean. Spends most of his childhood in the south of England and in Berwickshire.

1929: Moves with family to Anzin, near Valenciennes, France. He takes a keen interest in politics and demonstrates an interest in art.

1938: Moves to London.

1939: Joins the army. Finds work in the Defence Ministry.

1940s: Marries Patricia, a violinist. Socialises with leading literary and artistic figures, including Lucian Freud and Herbert Read. Works in the Ministry of Information and the Charities Commission.

1947: Moves to Glasgow, settling in a studio on Sauchiehall Street and painting full-time. Quickly aligns himself with the “Independents” and the artists associated with J.D. Fergusson’s New Art Club.

1948: Meets second wife, Helen Margaurite Watson.

1950: Earliest recorded exhibition at International House, Edinburgh, with Bet Low, Tom MacDonald and William Senior. Creates work in an abstract vein and often focusses on religious and moral themes.

1954: Significant solo exhibitions at McLellan Galleries and the British Council, both in Glasgow. Works are largely figurative and experimental.

1955: Birth of daughter, Cherie. Scholarship at Cercle Culturel de Royaumont. Meets Alain Robbe-Grillet, writer and filmmaker. Solo exhibition at Galerie Ray, Paris.

1956: First known article written for publication. Contributes to open air exhibitions by Glasgow’s Botanic Gardens. Around this time, Lavalle shows an increased interest in landscape and begins to work with enamel paints.

1957: Delivers first lecture with Glasgow University Extra-Mural Department.

1959: Spends time in North Strome, near Wester Ross, which inspires a greater interest in landscapes.

1961: Moves to Maryhill.

1962: Publishes first Scottish Field article (April).

1964: Last Scottish Field article (March).

1968: Receives Scottish Arts Council bursary. Solo exhibition at McLellan Galleries, Glasgow.

1969: Solo exhibition at Traverse Theatre Art Gallery, Edinburgh.

1970: Solo exhibition at Confederation Art Gallery and Museum, Prince Edward Island, and other venues in Canada. Last recorded lecture.

1971: Retrospective exhibition at NB (North Briton) Gallery, Gartocharn. Suffers a breakdown and is hospitalised. His studio is vandalised in his absence. Around this time, his marriage ends.

1973: Second solo exhibition at NB Gallery, Gartocharn.

1975: Third solo exhibition at NB Gallery, Gartocharn. Organises exhibition of work by local artists for gala day at Maryhill Park.

1976: Involvement in a group show at NB Gallery, Gartocharn, amounts to the last real evidence of art activity.

1990: Retrospective at Pearce Institute, Glasgow.

2002: Dies of pneumonia at Stobhill hospital, Glasgow.

Appendix B: Exhibitions

The below appendix provides a comprehensive list of all known solo exhibitions of Lavalle’s work, as well as all known contributions to group shows. This list is probably incomplete: Lavalle almost certainly contributed to the monthly exhibitions held by Fergusson’s New Art Club, for example, but these and other contributions have been omitted due to limited documentary evidence.

Solo exhibitions

1954: British Council, Glasgow; McLellan Galleries, Glasgow.

1955: Galerie Ray, Paris.

1968: McLellan Galleries, Glasgow.

1969: Traverse Theatre Art Gallery, Edinburgh.

1970: Confederation Art Gallery and Museum, Prince Edward Island, and other venues in The Maritimes, Canada, including St Mary’s Art Gallery.

1971: NB (North Briton) Gallery, Gartocharn.

1973: NB Gallery, Gartocharn.

1975: NB Gallery, Gartocharn.

1990: Pearce Institute, Glasgow.

2023: Nicolls, Glasgow.

Group exhibitions

1950: International House, Edinburgh, with Bet Low, Tom MacDonald and William Senior.

1951: Institut Francais d’Ecosse, Edinburgh, with Donald Bain; Casa d’Italia, Glasgow, with Alfredo Avella, Bet Low, Luigi Marzaroli, Tom MacDonald, Carlo Rossi, Silvio Rossi and William Senior.

1952: McLellan Galleries, Glasgow, with Luigi del Pizzo.

1953: Riddle’s Court, Edinburgh, with Smeaton Russell; International House, Edinburgh, with John Morrison and Smeaton Russell; University Graduates Club, Glasgow, with Donald Bain and John Morrison.

1955: Artists International Association Gallery, London, and a further unknown venue in Copenhagen, with Robert MacGowan, Luigi del Pizzo, Alistair Russell and Smeaton Russell.

1956: Centre for Musical Interpretation, Hampstead, with Robert Culff, Peter King and Smeaton Russell; Open Air Exhibition, Glasgow, with Bet Low, Tom MacDonald, Brian Millar, William Rennie, William Senior and others; McClure’s Gallery, Glasgow, with Robert Crolla; McLellan Galleries, Glasgow, with Donald Bain, Alan Fletcher, Millie Frood, Bet Low, Tom MacDonald and others.

1961: Fine Art Society Annual Exhibition, Dumfries and Galloway.

1969: Compass Gallery, Glasgow, with Neil Dallas Brown, William Crozier, Bet Low, Tom MacDonald, Anda Paterson, Robin Philipson, Carlo Rossi, James Spence and others.

1970: Traverse Theatre Art Gallery, Edinburgh, with Carole Gibbons, Kelvin Guy and Knox [note: Knox is not to be confused with Jack Knox, 1936-2015].

1975: English Speaking Union of the Commonwealth, Edinburgh, with Isobel Beresford.

1976: NB Gallery, Gartocharn, with Andrew Binnie, William Birnie, Bet Low, Tom Shanks, Gordon Wyllie.

Note: Lavalle also contributed to “Exhibition of Paintings and Drawings” at Iona Community House, Glasgow, with Ian Finlay, Marion Finlay, Bet Low, Tom MacDonald and William Senior. The exhibition ran from 20 May to 2 June in an unknown year. Note that Ian Finlay is the artist who became better-known by the name Ian Hamilton Finlay.

Note: J.D. Fergusson invited Lavalle to contribute to a group exhibition entitled “Some Painters I Admire”, which opened at 299 West George St, Glasgow, on 26 January 1960. Although highly likely that Lavalle showed work, there is no evidence to suggest that he did.

Appendix C: Scottish Field

The below appendix outlines Lavalle’s contributions to Scottish Field from April 1962 to March 1964, with reference to the artist(s) concerned in each article.

April 1962 (pp.43-4): Douglas Abercrombie, Carole Gibbons.

May 1962 (pp.29-31): Alfredo Avella, Dympna Foy, Tom MacDonald.

June 1962 (pp.23-5): Joan Eardley, James Morrison.

July 1962 (pp.43-45): William Crosbie.

Aug 1962 (pp.28-19): Alasdair Gray, Bet Low. Also refers more briefly to Douglas Abercrombie, Jean-Michel Atlan, Carole Gibbons, Benno Schotz, James Spence, Keith Vaughan.

Sep 1962 (pp.37-8): Fred Pollock, John Taylor.

Oct 1962 (pp.107-111): William Gillies.

Nov 1962 (pp.87-89): Ernest Hood, Tom MacDonald.

Dec 1962 (pp.89-91): Ian Campbell and Shelagh Hoftetter.

Jan 1963 (pp.14-15): Elizabeth Blackadder, William Crozier, David Donaldson, Paul Klee, Anne Redpath.

Feb 1963 (pp.67-68): John Maxwell.

Mar 1963 (pp.67-69): Hamish MacDonald, Alasdair Taylor.

April 1963 (p.59): Gordon Gray, David Sinclair.

May 1963 (p.57): J.D. Fergusson; (p.77) Anita Rushbrook, Tom MacDonald.

June 1963 (p.37): Elizabeth Blackadder, John Bratby, William Gear, William Gillies, Oscar Goodall, James Harrigan.

July 1963 (pp.42-37): Lily Creegan, John Mathison.

Aug 1963 (p.43): Douglas Abercrombie, David Donaldson, Carole Gibbons, Oscar Goodall, Jack Knox, James Morrison.

Sep 1963 (p.16): “The Confraternity: 1903-63”; an extensive list of names aligned to artistic grouping/allegiance.

Oct 1963 (pp.45-6): Lavalle on art as therapy in hospitals.

Nov 1963 (p.91-3): David Donaldson.

Dec 1963 (p.119): Anthony Armstrong, Rosalind Bliss, Hugh Bulley, Edward Burra, William Crozier, David Donaldson, Howard Hodgkin, Harry Kingsley, Robert Leishman, Alexander McNeish, Angus Neil, Phillip Reeves, William Rennie, Carlo Rossi, Benno Schotz.

Jan 1964 (p.48-9): Pat Douthwaite, James McNeill Whistler, Edward Whitton.

Mar 1964 (pp.77-79): Edward Atkinson Hornel.

Appendix D: Lectures

The below appendix outlines the subjects and locations (where available) of Lavalle’s known lectures from 1957 and 1970. Note that each title refers to a series, typically comprising ten or twenty individual presentations.

1957: “Modern Painting”, Glasgow Arts Centre, Glasgow.

1957/58: “Appreciation of Modern Art”.

1959/60: “Art Appreciation: Evolution of Art Forms”, Ayr.

1960/61: “Art Appreciation: Twenty 20th Century Artists”, Gracefield Arts Centre, Dumfries.

1961/62: “Contemporary Art”, Lochgilphead and Campbeltown; “Art Appreciation”, Gracefield Arts Centre, Dumfries.

1963/64: “Contemporary Art”, High School, Oban.

1964/65: “The American School of Painting”, High School, Oban,

1965/66: “Art and the Influence of Religion”, Academy, Sanquhar. Delivered with A.D. Galloway; “Art Appreciation: The Background Story”, Academy, Annan; “The Fine Arts in Scotland”, High School, Dalbeattie.

1966/67: “Modern Scottish Art”, Queen’s Park Secondary School, Glasgow.

1967/68: “The Art of the Renaissance in Italy”, Grammar School, Dunoon; “A Course on Modern Painting”, Langside College of Further Education, Glasgow.

1968/69: “Art Appreciation: Baroque and Rococo”, Grammar School, Dunoon; “Technique and Method”, Langside College of Further Education, Glasgow.

1969/70: “Technique and Method”, Langside College of Further Education, Glasgow; “Art Appreciation”, Grammar School, Dunoon.

This text owes a very great debt to information gleaned from a large book of letters, photographs, typescripts, newspaper cuttings and other material collected by Lavalle himself, now in possession of the artist’s family. Without access to this trove of information, this text would not have been possible. Any attempt to accurately source-reference the information found in this book would be inadequate: newspaper cuttings, for example, some of the most valuable pieces contained within the book, are often unidentified and undated. Therefore, the section below comprises explanatory notes and references which relate to any sources consulted outside of this book. I will be very happy to provide insight into specific points in the text for anybody who wishes to get in touch, and will endeavour to identify the relevant sources as accurately as possible.

1: Lavalle is understood to have been an entirely self-taught artist. This has never been established beyond doubt, but no evidence exists to disprove it. While Lavalle’s daughter, Cherie, points out that he may have attended the art college in Valenciennes, any evidence to verify this has yet to surface.

2: Alasdair Gray, “Pierre Lavalle” in Pierre Lavalle: Paintings, 1947-75 (Glasgow, 1990), p.4.

3: The full name of Lavalle’s first wife, Patricia, is unknown; Freud (1922-2011) was an acclaimed British figurative painter; Thomas (1914-1953) was an acclaimed Welsh poet and writer; Read (1893-1968) was an English art historian, writer and noted anarchist; Mannin (1900-1984) was an English novelist and political activist. Other notable figures in Lavalle’s circle included Guy Aldred (1886-1963), British anarcho-communist who edited a series of anarchist periodicals from a base in Glasgow; and Meary James Thurairajah Tambimuttu (1915-1983), Tamil poet, critic and publisher, who founded the periodical “Poetry London”.

4: It is worthwhile noting that none of these assertions have been established beyond doubt, but are strongly suggested by a number of sources. Any evidence to disprove them has yet to come to light.

5: Gray, “Pierre Lavalle”, pp.4-6.

6: Ibid, p.4.

7: Ibid, p.6.

8: Ibid.

9: Macrae opened the 1953 exhibition at the University Graduates’ Club; Redpath opened the 1953 exhibition at International House.

10: There is a story that Fergusson helped to finance an exhibition of Lavalle’s work. If true, the exhibition in question was probably Lavalle’s 1954 solo show. However, although the story seems likely, there is no evidence to confirm it.

11: Lavalle may be referring to Isi Metzstein (1928-2012) or Andy McMillan (1928-2014), both then beginning their careers in architecture. Both would go on to become pre-eminent figures as partners in the well-known Glasgow firm Gillespie, Kidd and Coia. Both were enthusiastic collectors of Lavalle’s work.

12: The BBC bought a painting titled “The Fish That Died in the Desert” in July 1950 for £3, 3 shillings.

13: It is unclear as to whether the tapestry commission materialised.

14: Alasdair Gray, A Life in Pictures (Edinburgh, 2010), p.121.

15: Ibid, p.120.

16: Honeyman (1891-1971) was Director of Kelvingrove Art Gallery and Museum from 1939 to 1954; Bliss (1900-1984) was Director of Glasgow School of Art from 1946 to 1964.

17: Turner (1927-1998) was a Scottish poet, critic and editor of “The Poet” pamphlet; MacCaig (1910-1996) was an influential Scottish poet and teacher.

18: For example, Lavalle opened an exhibition of work by Erik Hogulnd [sic] and Alastair Russell in the premises of the British Council, Glasgow, in May 1953. He rebuked Glasgow’s establishment figures (“old die-hards”) in his speech.

19: A glance at cuttings from the art columns of the day reveal that in most instances, a critic’s text was very rarely illustrated.

20: Lavalle, “New Scots”, Scottish Field, April 1962, p.44.

21: Ibid, p.43.

22: Lavalle preserved letters from the public among his personal affairs.

23: Gray, “Pierre Lavalle”, pp.6-7.

24: Lavalle, “New Scots”, Scottish Field, November 1962, p.89.

25: See Lavalle, “New Scots”, Scottish Field, April 1962, p.44. Lavalle also refers to his interest in Dadaism in his 1961/2 lecture series.

26: Lavalle, “New Scots”, Scottish Field, December 1962, p.91.

27: Gray, “Pierre Lavalle”, p.7.

28: Lavalle was awarded a bursary of £150 in 1968.

29: Lavalle lived on Maryhill Road from 1961 until his death in 2002.

30: Gray, “Pierre Lavalle”, p.7.

31: “Pierre Lavalle: Painter and Art Publicist”, The Herald, 25 March 2002. Retrieved 09/11/2023. Please see this link: https://www.heraldscotland.com/news/12130553.pierre-lavalle-painter-and-art-publicist/

32: Gray, “Pierre Lavalle”, p.6.

I’m grateful to Richard Bath, editor of Scottish Field, who has kindly allowed me to reproduce an image from the September 1962 issue of the magazine.

I’m also grateful to Sarah Trombetti and the team at Great Western Auctions for allowing me to reproduce Lavalle’s painting “Christ and His Disciples in London”.

I’m also grateful to Henry Gibbons-Guy, who kindly provided a number of images of Lavalle’s work.

Above all, I’m sincerely grateful to Pierre’s daughter, Cherie, whose kindness in allowing me to access material on her father held in the family’s collection led directly to the creation of this text. I’m also very grateful to Cherie for answering a number of questions on her father and for providing many images of his work.

All images are reproduced courtesy of Cherie and with her permission, unless otherwise stated.