Portraits of the Tay: Part 1

Jane Adamson navigates the Tay from source to sea, with a new visual perspective, looking at people, rather than places, and tracking down their portraits.

PART ONE: HIGHLAND TAY TO CARSE OF GOWRIE

Earlier this year the BBC screened the documentary ‘The River: A Year in the Life of The Tay’ (2019) where author Helen Macdonald followed Scotland’s longest river, over four seasons.

Inspired, I wanted to know if I could make that same journey via some of the men and women who have been influenced by this great river, and how they have been portrayed. So evolved my personal selection of portraits, through which I have attempted to illustrate diverse occupations and interests. Their portraits linearly follow the river, source to mouth, so there is a chronological leaping back and forth. To make it manageable for both reader and author, I have divided it into two parts: Highland Tay to Carse of Gowrie and Dundee to North Sea.

Finally, I have excluded all painters. For that would be quite another story.

1. HIGHLAND TAY

The source of this river with the largest outfall of water in the UK is in the Highlands, at the foot of Ben Lui, a ‘Munro’, named after Sir Hugh Munro.

SIR HUGH THOMAS MUNRO (1856 -1919): MOUNTAINEER

Peaks over 3000 feet in Scotland are called Munros. They were named after Sir Hugh. Climbing all of them is a national sport. How did it come about? In 1891 Hugh Munro was asked by the Scottish Mountaineering Club to list all the hills in Scotland above 3000 feet. He was an ideal candidate, as he had become fascinated by mountain topography after a spell in The Alps. On the nearby Kirriemuir family estate he took long expeditions into the hills to record mountain heights.

In May 1879, he notes his first peak, Ben Lawers, above Loch Tay. At 3,984 ft (1,214 m), it is later confirmed as the 10th highest mountain in Scotland.

Here he is in The Great Tapestry of Scotland, kitted out in his Glengarry bonnet and walking tweeds.

Joan Kerr, Sir Hugh Munro, Panel 117, stitched in Fort William to a design by Andrew Crummy, courtesy of The Great Tapestry of Scotland, Galashiels

JOHN, 4th DUKE OF ATHOLL (1755 – 1830): SCOTTISH PEER, LANDOWNER AND TREE PLANTER

Edwin Henry Landseer, Study of the Duke of Atholl and his Keeper, John Crerar, for The Death of The Stag in Glen Tilt, oil over pencil on prepared paper laid on canvas, Dimensions Unknown, private collection

Much of this Highland Tay is part of the Duke of Atholl’s estate.

After the turbulence of The Battle of Culloden in 1746, there followed a time of peace which brought opportunities for Scottish agricultural improvement and experimentation. John, 4th Duke of Atholl, embodied this period. He was nicknamed “The Planting Duke” for planting 20 million trees and introducing Japanese Larch to the UK.

This oil and pencil sketch shows him seated beside his keeper, John Crerar, a man who served him virtually all his life. It is a study for a painting ‘Death of the Stag in Glen Tilt’. The focus on the two men is affectionate and trusting, Crerar in the dominant position, gun in hand, standing guard.

JOHN CRERAR (1749-1840): GAMEKEEPER, FIDDLER AND COMPOSER

Edwin Henry Landseer, The Keeper, John Crerar and his Pony at Blair Atholl, oil on board, 59 x 43cm, 1824, courtesy of Perth Art Gallery, exhibited in The Perth Museum.

John Crerar, the keeper. This was painted on Landseer’s first visit to Scotland, at just 22. Landseer has already caught the eye of the aristocracy and is on his way to royal patronage and knighthood. A child prodigy first exhibiting works in the Royal Academy aged 13, Landseer goes on to be particularly associated with animal portraiture and Scotland (viz. his stag portrait “The Monarch of The Glen” 1851). Crerar’s triangular white cravat mirrors the pony’s white star on his forehead. The eyes are to the hills.

Crerar is a capable 75 years old in this painting, who goes on to live to a remarkable 90: Highland air and a convivial life agree with this keeper, fiddler, and composer. His lively reel ‘The Marquess of Tullibardine’ (a family name of the Dukes of Atholl) is still played today: quite a legacy.

JAMES HUTTON (1726 – 1797): GEOLOGIST

Sir Henry Raeburn, James Hutton, Geologist, oil on canvas, 125.1 x 104.8cm, c.1776, courtesy of the National Galleries of Scotland, Scottish National Portrait Gallery.

John, 4th Duke of Atholl also cultivated the men of letters of his day. In the summer of 1785 he invited James Hutton to stay in his hunting lodge, Forest Lodge.

Hutton, an Edinburgh man, is often referred to as the ‘Father of Modern Geology’. On this visit his observations of the rock exposures by the bridge of Dail-an-eas on the River Tay, demonstrated that granite was formed by cooling of the rock, confirming geological features were not static but continued to transform over long periods of time.

The Dail-an-eas bridge collapsed in the early 1970s. It was not the first bridge to collapse across the Tay.

This fine 1776 portrait is by a young Henry Raeburn (he was 20), when Hutton was already famous. At first glance we are struck by Hutton’s solemnity and composure, his papers and fossils on the table, but note how nonchalantly his left arm is slung over the back of the chair: a quirky touch of verve.

2. DUNKELD

Leaving the Highland landscape we move down river to the cathedral town of Dunkeld, an old crossing point of the River Tay and to another fiddler, perhaps Scotland’s most famous composer of traditional Scottish music, Niel Gow.

NIEL GOW (1727 -1807): FIDDLER AND COMPOSER

Gow lived all his life near The Tay. His family moved to Inver, a hamlet outside of Dunkeld when he was an infant and he continued to live there until his death. Here he is in middle age playing with his brother Donald.

David Allan, Niel Gow, Violinist and Composer, oil on canvas, 58.8 x 45.6cm, c.1780. Courtesy of the National Galleries of Scotland.

His fiddle playing started at a young age. He was amongst those performing in Dunkeld House when Charles Edward Stuart, Bonnie Prince Charlie, visited in 1745.

WILLIAM MURRAY, MARQUIS OF TULLIBARDINE (1689 -1746): NOBLEMAN AND JACOBITE SUPPORTER

Unknown artist, William Murray, Marquis of Tullibardine, Dimensions Unknown

Charles Edward Stuart was in Dunkeld House at the invitation of William Murray, Marquis of Tullibardine, who had assumed the rights of the Dukedom from his brother, James, who was in London avoiding Scottish turmoil. This portrait shows a youthful Marquis, but by 1745, he was a man in his 50s, worn out by exile, poverty abroad and conflict. In 1746 he supported the Jacobite Cause in the Battle of Culloden and managed to escape, but infirmities and age meant he was captured, subsequently dying in the Tower of London: a fate of so many.

Niel Gow, in the stability of the years that followed, went on to become an admired fiddler. James, 2nd Duke of Atholl, on his return from London, became his patron.

JAMES MURRAY, 2nd DUKE OF ATHOLL (1690 – 1764): LANDOWNER AND PATRON

Allan Ramsay, James Murray, 2nd Duke of Atholl, oil on canvas, 73.7 x 61cm, 1743, courtesy of the National Galleries of Scotland.

I like the contrasting portraits of these two aristocratic brothers. There is a facial resemblance even if their political outlooks and dress sense differed. I cannot help but feel that Allan Ramsay’s unflinchingly cold study of James, 2nd Duke of Atholl, was coloured by what was happening in Ramsay’s life at the time. 1743 was the year Ramsay’s first wife Anne died giving birth to their third child.

But back to happier times and Gow, who deserves a second portrait.

I first encountered Niel Gow via his portrait in the ballroom of the Duke of Atholl’s Blair Castle, decades ago, musing what an extraordinary fiddler he must have been, to have been painted by Sir Henry Raeburn.

Sir Henry Raeburn, Niel Gow, oil on canvas, 123.2 x 97.8cm, 1787, courtesy of the National Galleries of Scotland, Scottish National Portrait Gallery

Outliving his aristocratic patrons, Gow lived to 83 and continued to compose until his death. Aptly, his final tune was to commemorate the new bridge over The Tay; ‘Dunkeld Bridge’.

His legacy lives on in the annual Niel Gow Music Festival held in Dunkeld. His statue greets you, fiddle in hand, before you cross the bridge into the town.

Seven men of The Tay, but what of the women?

BEATRIX POTTER (1866 – 1943): AUTHOR, ILLUSTRATOR, NATURAL SCIENTIST, AND CONSERVATIONIST

Born into a Victorian upper middle-class family, the author and illustrator Beatrix Potter spent over a decade of summers from 1871on holiday with her family on the western banks of the Tay, at Dalguise House. A few miles north of Dunkeld, it is on a stretch of river known for its exceptional fishing, which was why the family had come in the first place. It was here that Peter Rabbit, subject of her most successful children’s book, first took shape in a letter to her governess and it was here that she considered her happiest moments in life were spent.

Sir John Everett Millais, the Pre-Raphaelite painter, a regular visitor to Dalguise, gave her encouragement: plenty of people can draw’ he once told her ‘but you and my son John have observation’. (note 1)

Beatrix Potter at Dalguise House, with her spaniel, Spot. Photo courtesy of Victoria and Albert Museum, London

Another early influence on Beatrix Potter was Charles McIntosh, a local man from Inver, a learned but shy postman and naturalist. Her first scientific collaborator, he helped her draw and identify fungi. He was surely a model for Mr McGregor, as seen below.

Charles McIntosh, photo courtesy of Perth Museum.

Beatrix Potter, Sketch of Peter Rabbit and Mr McGregor, 1927, Dimensions Unknown, private collection

3. CAPUTH

Until now I have barely spoken about fishing, or that the River Tay used to teem with salmon. Over the centuries salmon fishing rights have been a closely guarded privilege, of the monasteries and then of individuals who owned stretches of the river, or its pools.

Holidays spent shooting and fishing were primarily for the wealthy; but also a few others.

GEORGINA BALLANTINE (1889 -1970): NURSE, REGISTRAR, AND SALMON FISHER

In 1922, Georgina Ballantine, a ghillie’s daughter, landed the largest line caught salmon in the UK. At 64lb (just over 29 kilos) it is a record that has never been beaten. Georgina, a nurse in her early 30s, was accompanying her father when she landed the salmon on the Glendelvie Water by Caputh.

Georgina Ballantine, photo courtesy of Perth Museum.

Georgina was photographed, but not painted. It was the fish who had that privilege with a watercolour by AG Rennie which hangs in the Fly Fishing Club in London. In 1922 a fish could enter the club, but not a woman. And today? Times change but the club still has no lady members.

The cast of the salmon is in the Perth Museum.

As an interesting aside, Georgina’s father was ghillie to the Lyles, of Tate and Lyle, the Golden Syrup manufacturers. 1922 was a special year for them too: they were awarded a royal warrant.

Syrup from sugar, the sugar trade: now that will feature again, down river.

4. PERTH

In Perth, the river’s fresh water turns saline. The Tay is tidal just beyond the city. Given its central location in Scotland there has been a settlement here since prehistoric times. Nearby is Scone Abbey, which used to house the Stone of Scone (The Stony of Destiny) where the Scottish kings were traditionally crowned. Given its royal associations it has a wealth of history.

I have chosen two characters for Perth, the first a beauty and artist’s muse, in line with Perth’s nickname ‘The Fair City’ (named after Walter Scott’s novel ‘The Fair Maid of Perth’) and the second, an outstanding colonial administrator. Both characterise the many Scots who having made their fortunes abroad, returned to Scotland. Both are buried in Perth.

EUPHEMIA CHALMERS GRAY, LADY MILLAIS (1828 -1897): ARTIST’S MODEL, ARTIST, AND WRITER

Born in Perth she grew up at the foot of Kinnoull Hill, in middle class wealth. Called Effie as a child, her family were friends of the art writer and critic John Ruskin. Nine years her senior he wrote the fantasy story ‘The King of The Golden River’ for her, when she was 12.

She married Ruskin, but after five years the marriage was not consummated. With great courage she filed for annulment, which caused a major public scandal, then went on to marry the pre-Raphaelite painter John Everett Millais the following year. They had eight children together.

John Everett Millais, Effie Millais, nee Gray, oil on canvas, 1873, 99 x 84cm, courtesy of Perth Art Gallery.

John Millais has painted his beautiful wife in middle age contemplation. Around the time they would be holidaying in Perthshire and visiting the Potters at Dalguise House. She is 45. The burgundy velvet of her dress reflects the colour in her cheeks. The monthly literary publication ‘The Cornhill Magazine’ is in her hand. It must have been hard to live with the scandal her second marriage caused, but here she seems at ease, rightly frowning at us all.

After a life of London and Perthshire society Effie (Gray) died in Perth aged 65 and is buried quietly, beside a son, near her childhood home in Kinnoull Churchyard.

THE HONORABLE MAJOR-GENERAL WILLIAM FARQUHAR (1774 – 1839): SCOTTISH COLONIAL ADMINISTRATOR, SIXTH RESIDENT AND CHIEF ADMINISTRATOR OF MALACCA AND FIRST RESIDENT AND COMMANDANT OF SINGAPORE

In the world of Scottish colonial administrators, William Farquhar must surely rate amongst one of the best. Born in Aberdeenshire, he took the high road to success, arriving in India (Madras) to join the East India Company in 1791 aged 17. An engineer and linguist (he spoke Malay), he established the British rule in Malacca when they took over from the Dutch, and proposed the settlement in Singapore, to become the First Resident and Commandant of the new colony.

Left to manage the colony for four years, he took a laissez-faire approach, an action his superior, Sir Stanford Raffles, did not approve of despite it encouraging trade. Farquhar was quickly dismissed. Acrimoniously.

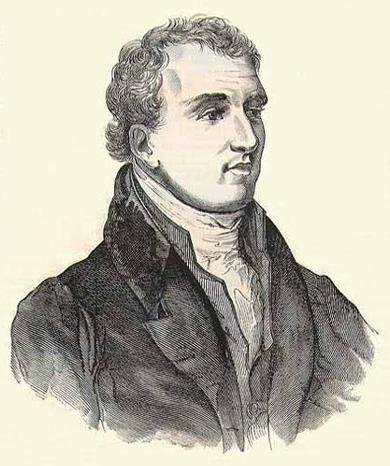

Artist Unknown, William Farquhar, c.1830.

Returning to Scotland in 1826, he settled in Perth and married Margaret Loban two years later. They had six children and through his eldest daughter, Farquhar is fifth great-grandfather to Justin Trudeau, 23rd Prime Minister of Canada.

The successful Scots diaspora.

He died in 1839 at Early Banks, Perth, aged 65. His mausoleum is in Greyfriars Kirkyard, Perth.

The above portrait may show him as he wished to be seen in his First Resident uniform and whilst Sir Stanford Raffles’ name is stamped all over Singapore, Farquhar’s legacy is pictorially elegant.

During his tenure as British Resident and Commandant of Melaka, Farquhar commissioned (unidentified) Chinese artists to paint the local flora and fauna of the Malay Peninsula. These botanical watercolours are of exceptional beauty, blending local artistry with scientific realism. Before the age of the camera, they played in a pivotal role in illustrating the region to the curious West.

‘The William Farqhar Collection of Natural History Drawings’ were donated by Farquhar in 1826 to the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland, who subsequently sold them in the 1990s. A Singaporean, Mr Goh Geok Khim, bought them and presented them to the National Heritage Board, Singapore in 1996. They went home.

I think Farquhar would approve.

Sago Palm/Pohon Rumbia/ Metroxylon Sagu from: Natural History Drawings, The Complete William Farquhar Collection Malay Peninsula 1803 - 1818, courtesy of The National Museum of Singapore.

A plant illustration neatly introduces our next portrait, of a plant collector.

5. SCONE AND KINNOULL

The early 1800s was a period of plant discovery particularly associated with the Scots.

Following The Battle of Culloden, peace allowed the Scots aristocracy to return to their estates and build new houses. Castle fortifications were no longer required, so houses overlooking grounds were being designed for pleasure not security. Grand houses required gardens, gardeners, and plants to show off their owner’s wealth and status.

DAVID DOUGLAS (1799 – 1834): GARDENER, BOTANIST, PLANT COLLECTOR AND EXPLORER.

Artist Unknown, David Douglas, Woodblock engraving from Louis van Houtte and Charles Lemaire's Flowers of the Gardens and Hothouses of Europe (1851)

David Douglas, born in Scone, was part of that transition. His father was a stone mason employed on the new Scone Palace for the Earl of Mansfield. It was a venture which increased the local population, brought prosperity, and the opportunity of education for working class children.

Douglas was sent to the Parish School of Kinnoull, where he strained against discipline, preferring birdwatching or fishing: a boy schooled in Kinnoull but educated by The Tay.

At 11 he was an apprentice gardener at Scone Palace, moving to Sir Robert Preston’s Valleyfield estate, where he met William Hooker, Professor of Botany at Glasgow University. Hooker went on to become one of the most influential botanists of the nineteenth century.

Hooker introduced Douglas to the Horticultural Society in London, who counted amongst its members the Tsar of Russia and several kings of Europe. They sent men on plant hunting expeditions across the globe.

Douglas was just their man. He was a knowledgeable botanist with curiosity and an ability to endure hardship. All those thrashings as a fidgety inquisitive child in Kinnoull Parish School had never daunted his independent spirit.

Sent to North America, Douglas returned with 240 new species of plants to Britain, before dying tragically young at 35 in Hawaii. The Douglas Fir is named after him.

SIR PATRICK GEDDES (1854-1932): BIOLOGIST, SOCIOLOGIST, GEOGRAPHER, PHILANTHROPIST AND PIONEERING TOWN PLANNER

Artist Unknown, Patrick Geddes, oil on board, 40.9 x 33cm, c.1930, courtesy of the National Galleries of Scotland

Of this next man, E.M. Forster was to say: “to sum up Patrick Geddes in a few lines would be impossible”. I will not even try: the man was a polymath.

But even polymaths start off as children.

Another Kinnoull boy, Patrick Geddes lived in Mount Tabor, a cottage on Kinnoull Hill, from the age of three to 20. As a child he would go for long walks with his father, which gave him a lifelong appreciation of green and open spaces. ‘I grew up in a garden’ he would later say.

Both his parents encouraged his creativity and scientific studies; his father building the teenage Patrick a shed for his experiments.

He would later write about the influence of these early countryside roamings:

“How many people think twice about a leaf? Yet the leaf is the chief product and phenomenon of life: this is a green world, with animals comparatively few and small, and all dependent upon the leaves.”

View from Kinnoull Hill, 2024, photo: Jane Adamson

This first-hand experience of place, ecology and botany - the interconnectedness and interrelationships - led to his geographical vision of The Valley Section. It was his belief that it took a whole region to make a city. Sitting above the city of Perth, observing urban life from a rural position, watching The Tay flow from urban Perth to industrial Dundee, it is not hard to see how his childhood surroundings influenced his future theories and practices.

He became the founder of Britain’s town planning movement, first making radical improvements to the slum dwellings of the seventeenth century buildings in Edinburgh’s Royal Mile, before going on to advise in India and Jerusalem. Amongst his many achievements, he is also considered the founding father of the science of ecology and “green” theories.

6. THE CARSE OF GOWRIE

From the heights of Kinnoull Hill we resume our journey along the northern bank of The Tay. The southern bank will need to wait, otherwise I will never get us to the mouth of the river.

The Carse of Gowrie: fertile low-lying lands by The Tay, stretch for about 20 miles between Perth and Dundee. Today it is a major soft fruit growing area but it has always attracted attention for its position and soils. Monks settled here after the Normans arrived in 1066, and later colonials flush with money - acquired overseas - bought estates.

Earlier settlers left their portraits in stone. This is sainted territory.

PICTISH MEN OF ST MADOES

St Madoes Stone - Pictish Cross Slab, carved sandstone, c.8th Century, Dimensions unknown, courtesy of Perth Museum. Photo: Jane Adamson

This Pictish cross slab was found lying flat over a grave in the St Madoes churchyard in the 1830s. It was set upright by the church door, until it was removed to the Perth Museum and Art Gallery in the 1990s. In the newly opened Perth Museum it has been given a prominent place and coloured lighting.

It is in remarkable condition. Carved on both sides, by two artists, it seems. On one side, it has a Christian face and on the other - the one I have photographed here - lions, hunting dogs, Pictish symbols, and hooded figures on horseback: monks, or travellers of a different sort?

JOSEPH KNIGHT (c1753 - ?): CAMPAIGNER AGAINST SLAVERY IN SCOTLAND

From St Madoes, we head towards Dundee, via the Ballindean estate, near Inchture, for the story and portrait of Joseph Knight. Knight was taken as a child from Guinea and sold as a slave to John Wedderburn in Jamaica in 1762. Wedderburn made him a house servant and brought him back to Scotland in 1769.

Knight then took Wedderburn to court for his freedom, in what was a landmark Scottish case.

But Wedderburn’s story first! He was the eldest son of Sir John Wedderburn of Blackness: a family of Jacobite supporters. After his father’s capture at The Battle of Culloden, young Wedderburn (aged 17) went to London to plead for his father’s life. Failing, he witnessed his father’s hanging, drawing and quartering as a traitor. With few prospects, he worked his passage over to America, and on to Jamaica where he became a surgeon, despite having no qualifications, acquired a sugar plantation and set up several trading ventures.

Wedderburn became wealthy and returned to re-establish the family fortunes and titles, by firstly purchasing the Ballindean estate. Joseph Knight came with him.

Nkem Okwechime, Joseph Knight, digital print on Panama Cotton, 300 x 100cm, 2023, courtesy of Perth Museum. Photo: Jane Adamson.

Knight, who had been taught to read and write, married another house servant, Anne Thomson from Dundee, and they set up house together. But Wedderburn took action to have Knight arrested. Knight appealed to the Sheriff of Perth and the court found in his favour ‘the state of slavery is not recognised by the law of this kingdom’. Wedderburn took the case to The Court of Session in Edinburgh, but the court again supported Knight and the judgement of Perth.

It was a historic judgement, and the death to slavery in Scotland.

This moving tale has spawned both a historical novel, ‘Joseph Knight’ by James Robertson (2003), and a play, ‘Enough of Him’ by May Sumbwanyambe (2022).

Nkem Okwechime, Joseph Knight, see above. Photo: Jane Adamson.

We do not know what Knight looked like so this banner screenprint in the Perth Museum wittily images his profile as a stamp, outlined against the beguilingly benign cowrie shell pattern, maps of his three significant homes, and the date of the judgement: 1778.

GEORGE PATERSON OF CASTLE HUNTLY (1734 – 1817): SURGEON, SECRETARY, AND ADMINISTRATOR IN THE EAST INDIA COMPANY; LANDOWNER, AGRICULTURAL POINEER IN THE CARSE OF GOWRIE

Sir Henry Raeburn, George Paterson of Castle Huntly, 1790, oil on canvas, 124.3 x 101cm, Courtesy of Dundee Art Galleries and Museums Collection.

Another Henry Raeburn portrait. This is in the Victoria Gallery in the McManus, Dundee’s Art Gallery and Museum, a gallery preserved as when it was first opened in 1889. The painting is hung at eye level, so you are face to face with George Paterson and the genius of Raeburn.

Born in Dundee, son of a master weaver, and educated at Dundee Grammar School, Paterson studied medicine in Edinburgh and Leiden, and then rose to the rank of surgeon in the British Army. He made his money in India as Official Secretary to Sir Robert Harland, when deployed into settling the affairs of the Nabob of Arcot for the East India Company.

Returning to Scotland a rich man, to be known in Tayside as the ‘Eastern Prince’, he married an aristocrat and bought Castle Huntly seen in the background of this portrait: a Dundee commoner with his new money.

Raeburn focuses on his face, and he has painted a book in hand for this intelligent man. The cloth-covered buttons of the jacket are so deftly done that you can almost feel the brushstroke on canvas. If Raeburn has captured the man, Castle Huntly is a poor shadow, but Paterson had spent a small fortune on its restoration, so it had to be in the picture. It signalled he had arrived.

If we began with a saint in the Carse of Gowrie at St Madoes Church we end with one at St Marnock’s Church, Fowlis Easter, within sight of Dundee and The Tay. This church is a few miles inland, for which I make no excuses, for here you will see some of the earliest painted portraits in the country.

MEN AND SAINTS OF ST MARNOCK’S CHURCH, FOWLIS EASTER, LATE 1400s

Fowlis Easter artist, Crucifixion, photo: Bruce Pert

National treasures! These are unique examples of Scottish church paintings from the 1400s: rare survivors that escaped The Reformation. They are exceptional paintings which have been written about in Issue 6 of Art-Scot by Gillian Zealand. (You can read Gilian’s piece here: www.art-scot.com/fowlis-easter

St Marnock’s Fowlis Easter was a collegiate church to St Andrews, supporting outlying churches and chapels, and producing a breviary now in the National Library of Scotland. It was a place of great importance, which Zealand talks about being part of the flowering of the arts under James III and James IV, two kings steeped in European Culture.

The weathered long faces of the north, acting out scenes from the Crucifixion. Who were the models for this? Were the paintings done by a European hand, or a Scots? We don’t know but we do know it is a singular pictorial glimpse of the men of the 1400s, in situ. Not whisked away to a museum, yet.

We have travelled from The Highlands to the western fringes of Dundee. From a mountaineer to the 15th century men of St Marnock, with aristocrats, a gamekeeper, fiddlers, a geologist, an author and an illustrator, a champion salmon fisher, an artist’s model, a colonial administrator, plant explorer, pioneering town planner and polymath, pictish men, a freed slave campaigner and a Tayside ‘Eastern Prince’ in between. This longest of rivers is rich in history, and we are not done yet. Next is through Dundee and onto the North Sea. We will pick up that path in Issue 10.

Jane Adamson

Note 1: Millais’ son, John, would go on to become a celebrated naturalist and wildlife artist