Portraits of The Tay

Part Two: Dundee to the North Sea

For those new to this escapade: let me recap. I am travelling down the River Tay via some of the men and women who have been influenced by it, and how they have been portrayed. It is a personal selection of portraits, my aim being to illustrate diverse occupations and interests. The portraits linearly follow the river, source to mouth, so there is a chronological leaping back and forth, and to make it manageable for both reader and author, the journey is divided into two parts: Highland Tay to Carse of Gowrie was in Issue 9 www.art-scot.com/portraits-tay and this is Part Two: Dundee to North Sea.

If you are still with me, let’s take the road to Dundee, passing on the right, The James Hutton Institute (pioneering solutions for global climate challenges and crop resilience) and on the left is Ninewells, a hospital known for its research, particularly in cancer.

1. LIFE AND DEATH

May as well start big, with two monumental portraits by Ken Currie.

The first was commissioned in 2001 by the Scottish National Portrait Gallery. It is of three men who were at the time all members of the Department of Surgery and Molecular Oncology at Ninewells Hospital and Medical School in Dundee. A painting to acknowledge their exceptional achievements.

It was also Ken Currie’s first official portrait commission.

THREE ONCOLOGISTS (2002)

Ken Currie, Three Oncologists, oil on canvas, 195 x 244cm, 2002 (Image courtesy of The National Galleries of Scotland)

Who were these exceptional men? They are listed, left to right, as shown in the portrait.

PROFESSOR RJ STEELE (b. 1952): CLINICAL EXPERT IN COLORECTAL CANCER SURGERY

PROFESSOR SIR ALFRED CUSCHIERI (b. 1938): PIONEER OF KEYHOLE SURGERY

PROFESSOR SIR DAVID P. LANE (b. 1952): DISCOVERER OF THE P53 GENE WHICH DESTROYS CANCEROUS CELLS BY TRIGGERING CELL SUICIDE

Extraordinary and busy: they are men on a mission.

From the Scottish National Galleries website, an explanation of the artist’s process: “unable to gather together for multiple portrait sittings he made life masks as a record of their appearance. However, Currie has stated that the commission was about more than recording likenesses.”

Spectral figures, wraiths looking back at us before they disappear behind the curtain into the bloody theatre of surgery. Ghostly trails waft above them. An intimately confronting painting.

In the gallery, here are Currie’s words accompanying the piece:

‘When I had a brief discussion with Sir David Lane about the nature of cancer, he said that people saw cancer as a kind of darkness and their job was to go in there and retrieve people from it, from the darkness as it were. Every picture has this key, you’re looking for that thing that will unlock the image, and that phrase was enough to unlock the thing for me’.

Ken Currie, Detail from Three Oncologists: Professor Sir Alfred Cushieri (courtesy of the National Galleries of Scotland)

But all is not darkness.

Before we move to our next portrait, let’s look out from Ninewells Hospital to the Maggie Centre below, designed by Frank Gehry, as a sanctuary for those with cancer.

Frank Gehry, Maggie’s Centre, Ninewells Hospital, Dundee

There is hope.

The next portrait is of a woman who has given that to many families. The second painting by Ken Currie of another Dundee professor. Aptly, it currently hangs back-to-back in Edinburgh with the Three Oncologists in the Scottish National Portrait Gallery.

Professor Lady Sue Black was Professor of Anatomy and Forensic Anthropology at Dundee University from 2003 to 2018 where she created, in 2005, the Centre for Anatomy and Human Identification at the University of Dundee.

She has undertaken forensic investigation in Iraq, Sierra Leone and Grenada and was the lead forensic anthropologist during the international war crimes investigations in Kosovo.

PROFESSOR LADY SUE BLACK, BARONESS BLACK OF STROME (b. 1961): ANATOMIST, FORENSIC ANTHROPOLOGIST, AUTHOR

Ken Currie, Unknown Man, oil on canvas, 199 x 275cm, 2019 (image courtesy of National Galleries of Scotland)

Ken Currie has Professor Lady Sue Black presiding over a draped corpse, where you almost expect a cool waxy hand to trail out, David-style, from its clinical cover. There is an inferred reference to wars and violence that the route of forensic anthropology took her. The red plastic bucket under the table emphasises the prosaic nature of the task. With her red hair electrifying above, she is central stage, in control but red eyed. Ken Currie reminds us that her mission is not without consequence: you cannot unsee the horrors of war.

Ken Currie, Detail from Unknown Man (courtesy of National Galleries of Scotland)

She has written about her experiences in her 2018 memoir All That Remains: A Life in Death. A humane and reassuring account of the lessons the dead can teach us. In March 2024 she was appointed to the Most Ancient and Most Noble Order of the Thistle, the highest honour in Scotland.

I have written less about these portraits than the others that follow, simply because they are so powerful. They need little explanation. It’s little wonder that the artist, Victoria Crowe, selected Three Oncologists as her favourite Scottish work of art.

2. CROSSING THE TAY

As The Golden Gate Bridge is to San Francisco, so the Tay Bridge is to Dundee: a definitive image of the city.

The Tay Bridge from the North Fife shore in Wormit, looking towards Dundee

Before 1877, the only routes to Dundee were by road or sail, until the railway came.

What follows is the tale of two bridges, two engineers, two World Tours, one poet and one almighty disaster.

SIR THOMAS BOUCH (1822 – 1880): RAILWAY ENGINEER, TAY BRIDGE DESIGNER

Thomas Bouch was the first designer of the Tay Rail Bridge. Bouch had a stellar career. He introduced the first roll-on roll-off train ferry in the world across the Firth of Forth, but his high point was the Tay Rail Bridge.

Unknown Artist, Sir Thomas Bouch, etching, date unknown

It was a phenomenon. American president General Ulysses S. Grant on his world tour commented on its construction ‘a mighty long bridge to such a mighty little town’. At over two miles, Bouch had designed the longest bridge in the world.

En route to Balmoral in June 1879, Queen Victoria crossed the bridge and knighted Bouch weeks later. It was a short-lived success. In December 1879 a storm blew part of the bridge down along with a train and all its passengers: no-one survived. The event ricocheted throughout the world.

Bouch being the designer was associated with disaster and died a few months after the inquest, aged 58.

A second bridge was built: the one that stands today. Completed ten years later, its opening was a low-key affair. The engineers were William Henry Barlow and his son, William. Barlow, in his 70s, had worked with Joseph Paxton on Crystal Palace, completed Isambard Kingdom Brunel’s Clifton Suspension Bridge, and was responsible for the magnificent train shed roof of St Pancras Station, London, which was the largest in the world when constructed. He was considered a safe pair of hands. They didn’t need another disaster.

WILLIAM HENRY BARLOW (1812-1902)

John Collier, William Henry Barlow, oil on canvas, 1880 (courtesy of the Library of the Institution of Civil Engineers)

We owe much to these talented and wealthy men of innovative engineering. Captured in their equally serious portraits, they come across as stilted; however, they were anything but. In their time they were at the cutting edge of a new industrial world, producing bridges and buildings that we still marvel at today.

Barlow is suitably serious though; for in 1880 he was on the committee investigating the collapse of the bridge.

At the same time as the portrait, a poet was writing about it; a man whose name is more familiar; someone who has inspired comedy, theatre, literature, film, radio plays, quirky annual dinners and a life of terrible poetry: William McGonagall.

WILLIAM MCGONAGALL (1825 -1902): WEAVER, ACTOR, POET AND TRAGEDIAN

Poor but colourful, his life was almost as disastrous as one of his most famous poems.

THE TAY BRIDGE DISASTER

‘Beautiful Railway Bridge of the Silv’ry Tay!

Alas! I am very sorry to say

That ninety lives have been taken away

On the last Sabbath day of 1879,

Which will be remember’d for a very long time.’

(The death toll was less than 90 but we do not turn to McGonagall for historical accuracy).

Where he was born is a little vague (Edinburgh or Ireland?); no matter, he lived most of his life in Dundee. His parents were Irish, moving several times in search of work, before they settled in the city in 1840, where he was apprenticed to follow in his father’s trade as a handloom weaver. He took great pleasure in reading, particularly cheap editions of Shakespeare’s plays, entertaining his fellow workers with recitations. On one occasion they paid a local theatre owner to allow him to play the title role in Macbeth. Convinced the actor playing Macduff was jealous of him, McGonagall refused to die. Is that a picture of the man, or what?

McGonagall married a fellow mill worker in 1846 and they had five sons and two daughters, but when his eldest daughter had an illegitimate child in 1877, work became harder to find and he was seized with a new inspiration to write, and recite, poetry.

This career change led to his constant struggles with money. Sailing to London in 1880 and then New York in 1887 to seek his fortune, he returned to Dundee to perform his poetry at a local circus, where a crowd was permitted to pelt him with eggs, flour, potatoes and stale bread. Wildly popular, the show became so raucous, local magistrates banned it.

Naturally, McGonagall wrote a poem in response.

David Oudney, William McGonagall, screenprint, 1990 (courtesy of Dundee Museum and Art Galleries) (copyright: the artist)

Why this portrait? Two reasons: firstly, it is in the collection of the Dundee Art Galleries and Museums; and secondly, Oudney has conveyed in print McGonagall’s rocky life, sailing back and forth, from Dundee to London and New York seeking validation, brows as furrowed as the waves, scarf waving theatrically behind him as he holds a candle against the sea winds he faces.

He faced much but was not without friends. They funded a publication of his works Poetic Gems in 1890, to assist him financially, a publication tellingly still popular today.

Sadly, the tale ends badly. Ill treatment on the streets of Dundee meant he and his wife moved to Perth in 1894 and a year later, to Edinburgh, where he died penniless in 1902.

He wrote about 200 poems, his two Dundonian inspired ones The Tay Bridge Disaster and The Famous Tay Whale being his most well-known. He is commemorated by two plaques in Edinburgh and a square named after him in Dundee, but his legacy is his influence in literature and the arts. The Scots comedian, Billy Connolly, is one of his fans.

BILLY CONNOLLY (b.1942): SINGER, COMEDIAN, ACTOR

In 1994, Connolly embarked on a 54-night tour performing to live audiences around Scotland: Billy Connolly’s World Tour of Scotland. The journey was documented by a film crew, with extracts taken from his shows, but the comedian was at his most engaging as he mused to camera on places and people, his childhood and enthusiasms.

Before the Dundee gig, he introduces us to his love of McGonagall, wondering at the resilience of a poet who wrote ‘the first time a man threw a plate of peas at me’ (the first time?) then proceeds to recite his poem The Tay Bridge Disaster, atop a Dundonian landmark, the Law Hill, in a blizzard.

Like McGonagall before him, the show must go on, and before he takes to the stage that night he thinks, ‘perhaps I am about to do something great here’. He’s read the Visitors Book: Dame Nellie Melba, Harry Lauder, Frank Sinatra, The Beatles, David Bowie, Elton John, Yehudi Menuhin…

Bob Hope says it was the first time he played a tunnel. His venue? The Caird Hall.

For this larger-than-life character, I have chosen the largest portrait of the journey. But to see him we have to travel to his hometown of Glasgow.

Rogue One, mural based on Jack Vettriano’s “Dr Connolly, I Presume”, on a building in Dixon Street, near St Enoch Square, Glasgow

Three Scottish artists were invited in 2017, to paint Connolly in celebration of his 75th birthday: John Byrne, Rachel MacLean and Jack Vettriano. The latter chose to paint Connolly, 13 years earlier, whilst on that 1994 World Tour of Scotland, windblown on a coast near Orkney.

Vettriano’s original painting, gifted to the City of Glasgow, is on permanent display, but was also recreated as a huge mural by Rogue One.

Back to Dundee and the Caird Hall where Connolly performed.

Photographed on a sunny day, the Caird Hall lettering has cast shadows on the stone behind, much as the man who built and donated it to Dundee, Sir James Caird, cast long shadows. A man who made his fortune through jute.

Caird Hall, Dundee

3. JUTE, THEATRE AND EXPLORATION

For much of the nineteenth century, Dundee was the European whaling capital. Ships sailed north from Dundee to the Arctic at the beginning of every year, returning home in the autumn, having wholesale slaughtered whales to process into oil to be used in lamps. In the world before drilled oil wells, piped gas or electricity, whale oil lit homes and places of work. But from the 1830s onwards, as newer lighting methods were introduced, the whale oil was used to process a long rough plant fibre, jute, into coarse string threads.

The intertwining of jute grown in India, lubricated by whale oil from the Arctic, and woven into cheap bagging material, coincided with an Industrial Revolution’s worldwide demand for bulk packaging.

Dundee already had a long-established textile industry - wool, flax, linen - but it was jute that made its mill owners fantastically wealthy; wealth to spend on many things, including the arts.

SIR JAMES KEY CAIRD, 1st BARONET OF BELMONT CASTLE (1837 -1916): JUTE BARON, MATHEMATICIAN, PHILANTHROPIST

David Foggie, Sir James Key Caird, oil on canvas, 91 x 70cm (image courtesy of University of Dundee, Tayside Medical History Museum Art Collection)

James was the son of Edward Caird who founded the firm of Caird (Dundee) Ltd in 1832: his father was one of the first to weave cloth of jute warp and weft.

Succeeding his father in 1870, when he was 33 years old, he expanded and equipped the works with the latest machinery. Three years later he married 30-year-old Sophie Gray, literally marrying into the arts. Sophie was the younger sister of Effie Gray, wife of John Millais, and like her sister, an artist’s model.

SOPHIA MARGARET ‘SOPHIE’ GRAY (1843-1882): ARTIST’S MODEL AND WIFE OF SIR JAMES CAIRD

John Everett Millais, Portrait of a Young Lady, oil on paper, laid over panel, 30 x 23cm, 1857 (private collection)

Here she is, a sultry young beauty at 14, painted by her brother-in-law, John Millais. It is a sensual work, confronting us in a very contemporary fashion. She sadly suffered from mental problems, dying, it is believed, in part from anorexia, at 38.

Caird never remarried.

He went on instead to build the Caird Hall and fund the last major expedition of The Heroic Age of Antarctic Exploration: the attempt by Sir Ernest Shackleton to make the first land crossing of the Antarctic Continent; an attempt that failed but is recognised as an epic feat of endurance.

Endurance was the name of the ship that took the expedition there and the James Caird, the lifeboat named after their sponsor, is remembered for successfully setting off to find help to rescue the stranded crew.

SIR ERNEST HENRY SHACKLETON (1874-1922): ANTARCTIC EXPLORER

Frank Hurley, Ernest Shackleton on board Endurance, photograph, 1914 (courtesy of the Scott Polar Research Institute, University of Cambridge)

The Australian Frank Hurley was the official photographer for Shackleton’s Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition (1914–1916). I don’t intend to relay the widely known tale here. However, the impact of Hurley’s black and white photographs are as fresh today as when they were first developed. Imagine how they must have been first received. He pictured a hero as he wished to be seen. Shackleton chose this photo for his 1919 book about the expedition.

Caird, however, never got to see or know the end of the story; or hear of his boat being dragged over the ice. He died in 1916, just shy of his 80th birthday.

Frank Hurley, Relaying the James Caird Across the Ice, photograph, 1916

Frank Hurley, The Departure of the James Caird: Elephant Island, photograph, 1916

Nor did Caird hear of or see the stranded crew waving the boat off, to hopefully find help.

On that note, we leave Sir James Caird and his story, for another one influenced by polar expeditions.

4. HEART OF THE CITY: A BIOLOGIST, MUSEUM CURATOR, BARD, MISSIONARY AND AUTHOR

If there was an A – Z of Dundee, Z would surely be for its Zoology Museum, named after our second polymath of this journey, Sir D’Arcy Wentworth Thompson.

SIR D’ARCY WENTWORTH THOMPSON (1860 -1948): BIOLOGIST, MATHEMATICAN, CLASSICS SCHOLAR, PHILANTHROPIST

An Edinburgh man, 24-year-old Thompson was appointed in 1884 as Professor of Biology at University College, Dundee. The following year he was elected Fellow of the Royal Society of Edinburgh, one of his proposers being Patrick Geddes.

In his 30s, he went on expeditions to the Bering Straits in 1896 and 1897. It was an international inquiry into the fur seal industry and their declining numbers. His final report drew attention to the near extinction of the sea otter and whale populations. He was one of the first to press for conservation agreements and species protection orders: a man ahead of his time.

He was in Dundee for 32 years before moving to St Andrews in 1917, where he was appointed Chair of Natural History. He remained there for the last 31 years of his life.

He is best remembered as the author of On Growth and Form, his 1917 book which led the way to explaining morphogenesis, the process by which patterns and body structures are formed in plants and animals. His mathematical examination of the beauty of nature stimulated scientists Julian Huxley, Alan Turing, Claude Levi Strauss, the artist Eduardo Paolozzi, and architects Le Corbusier and Mies van der Rohe. Willhemina Barnes-Graham heard him lecture in St Andrews and borrowed his book from the Cupar library to study the mathematics of nature.

To realise the extent of his influence in this field I highly recommend the article below, written by Matthew Jarron, Curator of Museum Services at the University of Dundee which includes the D’Arcy Thompson Zoology Museum.

Darren McFarlane, Scarus, Pomocanthus (Portrait of D’Arcy Thompson), 2012 (courtesy University of Dundee Fine Art Collections) (copyright: the artist)

I have chosen this contemporary portrait for its playful nature. It is based on a more formal portrait by David Shanks Ewart, and it is in the University of Dundee’s Museum Collection, whose curator is up next.

MATTHEW JARRON: CURATOR OF UNIVERSITY OF DUNDEE’S MUSEUM COLLECTIONS, ART HISTORIAN, AUTHOR

Matthew Jarron has been caught in guide mode: mid flow, hands expressively gesturing, the photo capturing his enthusiasm. Maybe not his best angle, but he is part of a new diorama map of Dundee. We don’t often get to see portraits of curators, so I am delighted to include this one. Curators, keepers and custodians acquire and develop collections and in so doing, inform and inspire us. We should treasure them more.

Sohei Nishino, Detail from Diorama Map of Dundee, 2023

Here is an example of a new commission doing just that, informing and educating us. The Japanese artist, Sohei Nishino, was asked by the V&A Dundee to create a large-scale photographic diorama map of the city to mark the 10th anniversary of Dundee’s designation as the UK’s only UNESCO City of Design. Nishino has produced other city series: Tokyo, London, Amsterdam, San Francisco, Rio de Janeiro and New Delhi. Dundee is the smallest city he has worked on.

Photo of Sohei Nishino in front of his Diorama of Dundee (image courtesy of V&A Dundee)

To give scale to the piece, here is he is in front of his map of Dundee, currently on display in the V&A Dundee. It must feature portraits of hundreds of Dundonians, but truthfully, I haven’t counted. So where is our curator, Matthew Jarron? Mid-way down the second panel from the left, keeping wisely well away from the neighbouring drinkers in a local bar.

There is an accompanying video to the piece, where Nishino explains his process of working. Typically, he spends a month in a city, exploring, and photographing people and places. Then three to four months back in his studio in Japan printing off his photos and using about 90% of them to compile his image.

Before he started this commission he said “I previously had an image of a small town on the outskirts of Scotland”. A month in the city changed that view, including his almost daily walk round The McManus, Dundee’s Art Gallery and Museum, where we are headed to next to discover the art and music of a Dundee native, Michael Marra.

MICHAEL MARRA (1952-2012): SINGER-SONGWRITER, MUSICIAN, PLAYWRIGHT

Marra is a contemporary Scottish cultural figure whose work over more than four decades has led him to be known as The Bard of Dundee.

In September a limited-edition box-set of his career was launched in the McManus Galleries. At the event, Scottish author Val McDermid sang his deliciously titled ‘Frida Kahlo’s Visit to the Taybridge Bar’ and American singer-songwriter Loudon Wainwright III performed his classic ‘Hermless’.

The limited-edition Michael Marra box-set displayed in the ‘Making of Modern Dundee’ Display at The McManus Gallery, Dundee (photo: the author)

Dundee’s Duncan of Jordanstone College of Art & Design have been behind the production of these box-sets and its Senior Lecturer, Eddie Summerton, has prepared an installation relating to the subject which is currently on show in The McManus. Brimming with images of this colourful man and his life, you can sense the fun had in its creation, with Frida Kahlo gracing the front of the box.

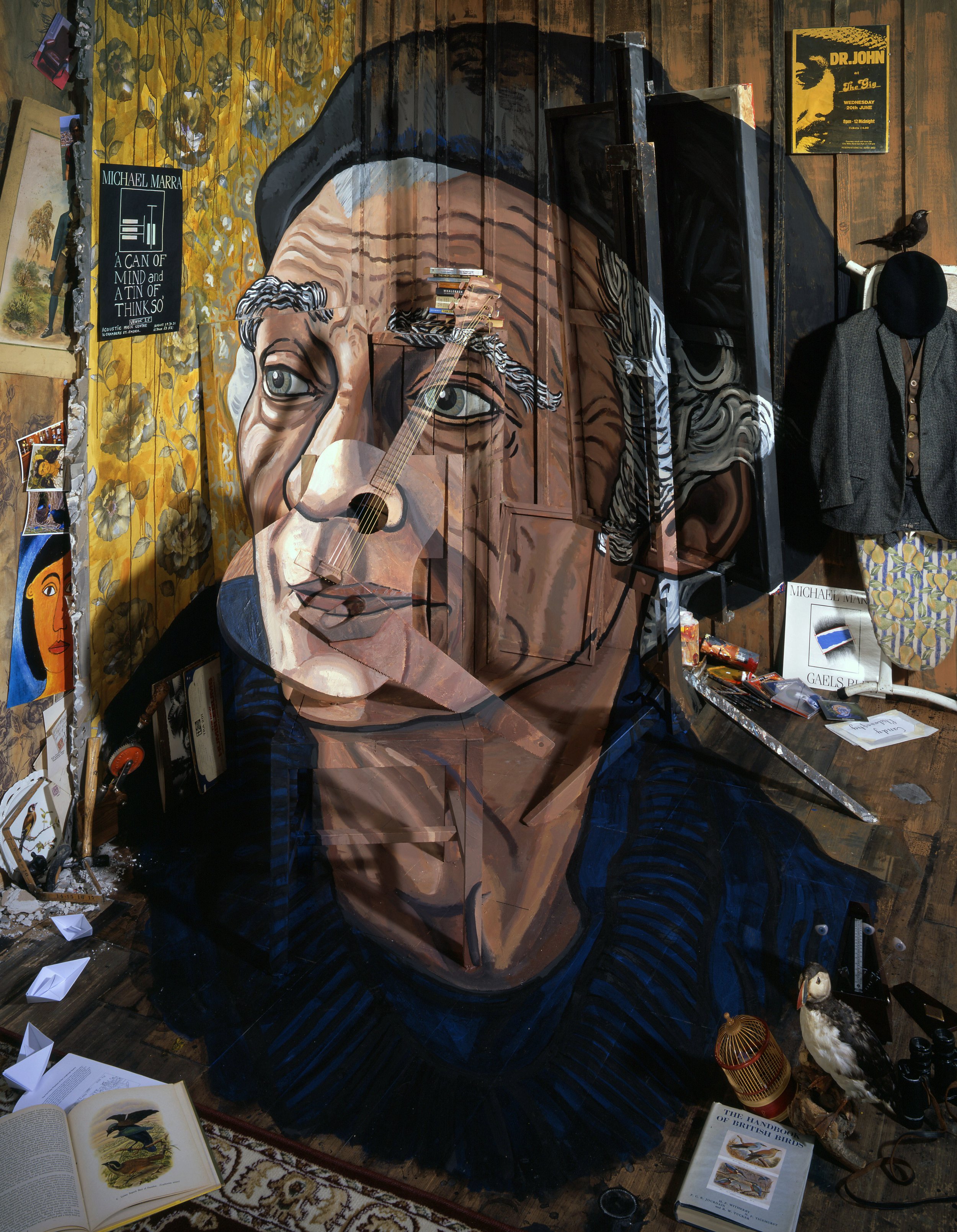

The portrait I have chosen of Marra is by another local artist, Calum Colvin, Professor of Fine Art Photography and Programme Director, Art & Media, Duncan of Jordanstone College of Art and Design.

Calum Colvin, Michael Marra, archival digital print on Baryta FB paper, 2017 (courtesy of Dundee Art Galleries and Museums) (copyright of the artist)

It is enlightening to see how this portrait was constructed:

‘Colvin’s constructed photographic artworks begin as large-scale studio ‘stage-sets’, tableaux of everyday objects, furniture and bric-a-brac carefully posed and theatrically lit.

Viewed from the fixed-point perspective of a large-format camera, painted trompe-l’oeil elements are introduced, integrating object and subject in a complex mise en scene. They are finally photographed on film, digitized and printed on to paper or canvas.’

(Extract from Calum Colvin’s website biography).

The effect achieves what all great portraits do, etching the facets of a life firmly in your mind.

Leaving the photographs and galleries behind, we head back out to the Tay shores and a small green park in front of the Caird Hall: Slessor Gardens, home to seasonal rock concerts, resting students and residents meeting up on the grass. It’s named after the missionary, Mary Slessor.

MARY SLESSOR (1848-1915): MISSIONARY

Now we move to a portrait that you could slip in your pocket! In 1997, The Clydesdale Bank issued their Famous Scots series of bank notes: Mary was the first Scots woman to feature on the front of a Scottish bank note. It illustrates the first part of her life, in Dundee.

Born in Aberdeen, she moved to Dundee when she was 11 and she began work as a ‘half timer’; half a day at school, half a day working in the Baxter Brothers’ Jute Mills. At 14, when her father and two brothers died, she became a jute worker, 6am to 6pm, helping support her mother and two sisters.

Clydesdale Bank Ten Pound note, 1997-2018

Her mother was a devout Presbyterian who read the monthly Missionary Record, and Mary developed an interest in religion. At 27, hearing of the death of missionary teacher and explorer, David Livingstone, she decided to follow in his footsteps.

At 28, she sailed to West Africa. The back of the note illustrates the second part of her life. It’s a map of Calabar in South East Nigeria, where Mary carried out her missionary work and lived amongst those she worked with, becoming fluent in the local language, Efik, and developing a deep knowledge of local customs and culture. She adopted local children rejected by their parents, as twins were considered at the time in Nigeria to be cursed, earning her the title of Eka Kpukpru Owo – ‘the mother of all peoples’. She is remembered today in Calabar on Mothering Sunday when women wear a waxen cloth embossed with her image.

By all accounts she was a shy modest soul who gave all credit for her achievements to God; but when she died in Nigeria, the country thought otherwise and gave her a state funeral.

The note was recalled in 2018, but I am amused to think Mary banked with a higher authority.

MARY SHELLEY (1797-1851): NOVELIST

From one Mary to another! Mary Slessor embarked on full-time employment as a mill worker aged 14 in 1862. Half a century earlier, an equally young 14-year-old, Mary Godwin, was shipped off by her father on the mail packet from Ramsgate to Dundee on a six-day journey. This was the Mary Shelley who only six years later wrote her 1818 novel ‘Frankenstein’ or ‘The Modern Prometheus’.

Early influences in life are often revealing. She stayed in Dundee for five months. Her novel has Frankenstein travelling from Switzerland along a route to the Orkneys ‘through Coupar, St Andrews and along the banks of the Tay to Perth’ but it is in the 1831 edition of Frankenstein that Mary reflects more tellingly on her experiences in Dundee:

‘I lived principally in the country as a girl, and passed a considerable time in Scotland. I made occasional visits to the more picturesque parts: but my habitual residence was on the blank and dreary northern shores of the Tay, near Dundee. Blank and dreary on retrospection I call them; they were not so to me then. They were the eyry of freedom, and the pleasant region where unheeded I could commune with the creatures of my fancy… It was beneath the trees of the grounds belonging to our house, or on the bleak sides of the woodless mountains near, that the true compositions, the airy flights of my imagination, were born and fostered’.

Richard Rothwell, Mary Shelley, oil on canvas, c.1831-1840, (courtesy of the National Portrait Gallery, London)

Here she is around the time she was musing on the short time she spent as a teenager in Dundee. But why was she there at all? Ostensibly Mary was instructed by her doctor to have six months by the sea to recover from an ailment in her arm. But why so far from London? Surely there was somewhere closer to hand.

Mary’s father, William Godwin, was a widower who had remarried. Perhaps all was not comfortable at home. A little distance was required. But more importantly he was a radical political philosopher. Few households would accept the daughter of such a man. The French Revolution had unleashed new ideas and political reforms which (aside from families) few communities would welcome. Dundee, however, had a tradition of radical thought.

A Dundee textile manufacturer William Thomas Baxter had met the Godwin family in London. With his two sons and five daughters, here was a like-minded family, interested in the liberal arts, in a radical town ready to welcome Mary; and foster her imagination.

The Baxter’s house, overlooking the Tay has long been demolished. Only a plaque in South Baffin Street marks the spot of what was countryside back in 1812.

5. THROUGH WEST FERRY, BROUGHTY FERRY AND ON TO THE NORTH SEA

Travelling on past the docks, oil rigs in for repair, wind farm stanchions ready to be taken out to sea, we drive into West Ferry. Let’s travel back in time, to view Dundee in 1879, to see what the town looked like from afar when the jute mills were booming and belching out smoke. Our viewpoint is the shore haven of a mansion house: Harecraigs, in West Ferry.

David Farquharson, Dundee from Harecraigs, oil on canvas, 1879 (image courtesy of Dundee Art Galleries and Museums)

You too would escape those mills, to sit sketching and playing on the beach, if you could. Which is exactly what the wealthy did, by building mansions of grandeur along the estuary.

We will look at one such house. Fort William was built for Captain Neish in 1835, it sits above the Tay on the Dundee Road as it heads into Broughty Ferry. Until recently, it was home to the Royal Tay Yacht Club.

Captain Neish was a man who successfully brought jute to the city and he and his wife are the subject of the following pair of paintings: recent acquisitions by Dundee Art Galleries and Museums.

CAPTAIN JAMES NEISH (1787-1867): MARINER

Captain Neish was the son of a Dundee merchant who first set out for India in 1807 where he was a ship’s captain in the employ of Scots merchants Jardine Matheson and Bombay merchant Jamsetjee Jeejeebhoy. From 1827, he commanded a ship called ‘Fort William’ which brought jute to Dundee in the early 1830s, the cargo being delivered to his relative, James Neish’s mill. Experiments to spin jute had been tried earlier but being more difficult to spin than flax, there had been little enthusiasm for the material. Rising costs in the early 1830s made manufacturers look to jute, which was cheaper than flax. Coinciding with the growing international trade in bulk commodities and the requirements of a series of wars, including the Crimean and American Civil War, fortunes were made. This was the start of one of Dundee’s key industries. Captain Neish named his house after his ship.

George Chinnery, Captain James Neish, oil on canvas, 30.1 x 26cm (image courtesy of Dundee Art Galleries and Museums)

Relaxed in his chair, grey haired, hint of a double chin, Captain Neish is looking comfortable in his yellow waistcoat - and comfortable with life.

MRS KATHERINE ANN NEISH (NEE WYLIE), MARINER’S WIFE

Captain Neish’s wife Katherine was also born in Dundee, and unusually for the period, followed her husband to India, living with him aboard his ship. She must have been a formidable soul for she gave birth to her third child on board the Fort William, in Macau in 1830.

Her portrait is of a different stamp. She signals her education via the open book, and control by her trim figure in a voluminous black and white dress clinched tightly at the waist. Dripping in jet jewellery: earrings to her collarbone, a necklace that would surely reach her knees and two wrist cuffs - she is making a statement.

There is a similar portrait by George Chinnery of a Mrs Da Silva in Macau with the same backdrop, sporting a similar white dress with the wide sleeves but none of the black trimmings or jet jewellery. Were Katherine Neish’s symbols of mourning?

But given the similarity of the portraits and Captain Neish’s grey hair, I think these portraits were painted in Macau where Chinnery established his studio from 1825 onwards (having escaped from his creditors in India). These are small portraits, not quite pocket-size but easily portable for a life at sea.

When I visited their grave in Dundee’s Western Cemetery, I could see the influence of the China Coast went with them to death. The position of the headstone follows the Chinese tradition for an auspicious burial ground: hill behind, water in front. It overlooks The Tay.

BROUGHTY FERRY

We’re almost at the end of our journey: Broughty Ferry. As you enter from along the Dundee Road, there is a blue and white plaque to remember Ian Chisholm who co-created the cartoon character Dennis the Menace, along with George Moonie and Davy Law. It is, however, another Broughty Ferry resident I am going to focus on: the cartoonist, Dudley Watkins, who also has a plaque, but not in blue and white.

At the outset, I said I would include no artists, but to journey down the Tay and not mention the Dundee publishers, DC Thomson, Dudley Watkins and comics would be wrong, so here they are.

DUDLEY DEXTER WATKINS (1907-1969): CARTOONIST AND ILLUSTRATOR

Born in England, Watkins came to the attention of the Dundee publishers, DC Thomson, in 1925 when they offered him illustration work on their magazines. In Dundee his skill as a cartoonist was noted and from 1933 onwards, he worked on comic strips.

In 1935, DC Thomson’s managing editor at the time, RD Low, decided to produce in their weekly newspaper, The Sunday Post, a fun section aimed at children. On 8th March 1936, stories drawn by Watkins of Oor Wullie and The Broons appeared. Iconic characters that still appear in that newspaper today.

Dudley Watkins, Oor Wullie, 1940 (image courtesy of DC Thomson)

Oor Wullie was reimagined in the summer of 2016 with the Oor Wullie Bucket Trail. Statues based on this character were installed across Dundee and Tayside, hand painted by artists with a different theme and later sold at auction for the ARCHIE Foundation at Tayside Children’s Hospital, Ninewells. It was such a success that it was repeated in 2019, with even more sculptures: a mark of the affection felt locally for the character Watkins created.

Oor Wullie Bucket Trail, outside the Caird Hall, Dundee, 2016

Following the 1936 comic strip success in the Sunday Post, DC Thomson decided to publish a comic solely aimed at boys and girls. On 4th December 1937, the first edition of The Dandy appeared, and with it, Watkins’ character of Desperate Dan: the incredibly strong cowboy with a formidable jaw who lived with his Aunt Aggie in Cactusville, and ate cow pies.

Dudley Watkins, Desperate Dan (image courtesy of DC Thomson)

And here he is striding through Dundee. A key figure on the city’s public art route.

Tony and Susie Morrow, Desperate Dan, bronze statue, 2.5m high, 2001

Months later in 1938, DC Thomson published their most popular comic, The Beano, for which Watkins drew a strip called ‘Lord Snooty’. Marmaduke, Earl of Bunkerton, who despite sporting a top hat and living in a castle, liked to spend time on the streets with his friends, The Trash Can Alley Gang.

Dudley Watkins, Lord Snooty (image courtesy of DC Thomson)

In this comic strip they meet their creator. Watkins has drawn his own bespectacled portrait smartly dressed in jacket and tie. Is the castle Lord Snooty and his gang emerge from the local Broughty Ferry one?

Watkins worked for DC Thomson for the rest of his life, dying aged 62 from a heart attack at his drawing board. He was a hard act to follow. DC Thomson reprinted Oor Wullie and The Broons strips for years before a replacement was found.

Today all three of these memorable characters - Dennis The Menace, Desperate Dan and Oor Wullie - are painted large on the side of the DC Thomson & Co Ltd building on the Kingsway Dundee. They are not forgotten.

From the page to the skies, and my last choice.

REV. THOMAS DICK (1774-1857): MINISTER, SCIENCE TEACHER, AUTHOR, CHRISTIAN PHILOSOPHER, ASTRONOMER

Born in the Hilltown, Dundee, Dick witnessed a meteor shower aged nine which gave him a lifelong passion for astronomy. His father was a small linen manufacturer, but Thomas did not follow him in to the trade. Instead, he became an assistant in a Dundee school, then supported himself through University in Edinburgh, taking out a licence to preach in 1801, having completed his studies as a student of divinity.

Decades of teaching followed, in Methven and Perth, but he continued to explore his fascinations in writing. His book The Christian Philosopher or the Connexion of Science and Philosophy with Religion, published in 1823, was a great success, and was reprinted many times.

He gave up teaching in 1827, aged 53, to write; and to build a small cottage on a hill in Broughty Ferry overlooking The Tay, fitted up with a small observatory and library.

The Philosophy of the Future State (1827) and perhaps the more interesting, his snappily titled 1838 book: Celestial Scenery; or The Wonders of the Planetary system displayed; illustrating the perfections of deity and a plurality of worlds. Dick believed in cosmic pluralism where every planet in the Solar System was inhabited. He calculated the Solar System to have 21 trillion-plus beings and speculated about the possibility of communicating with lunar inhabitants.

Artist Unknown, Thomas Dick, etching, date unknown

Looking at his faded portrait it is hard to believe he would be communicating with life on the moon; but appearances can be deceptive.

His writings were popular here and in the USA, and were satirised in 1835 in the newspaper The New York Sun in a series of articles called Great Astronomical Discoveries. And how about the so-called Great Moon Hoax: for that tale, an early example of fake news, I will refer you to Wikipedia.

On a more serious note, his admirers included the writer Ralph Waldo Emerson and the author of Uncle Tom’s Cabin, Harriet Beecher Stowe, who visited him in Broughty Ferry. Like Stowe, Dick believed in the abolition of slavery.

Elected a member of the Royal Astronomical Society in 1852, Dick died in 1857, aged 83.

When David Livingstone came to be awarded Freedom of Dundee later that year, he acknowledged Dick. Livingstone regarded Philosophy of a Future State as his biggest influence after the Bible and in his acceptance speech said ‘nothing would have given me greater pleasure than to have seen him at this time, but he is gone from amongst us’.

But perhaps not quite. There is a memorial to Dick in Broughty Ferry’s St Aidan’s churchyard, and in the heavens, Asteroid (9855) is named after him: Thomasdick.

With no photograph of the asteroid, you will have to visualise it, sitting outside Mars with an orbit about the size of Mount Everest. How many inhabitants would Dick have on his rocky planet? My imagination turns to another asteroid, the one conjured up by the French writer Antione de Saint-Exupery for his little prince.

But back to earth: I started with a mountain in the heart of the Scottish Highlands and have concluded it with an asteroid beyond Mars. From a mountaineer to an astronomer: it’s funny where journeys take you, if you let them.

This Tay journey has ended; perhaps for another to begin - out to the North Sea, the Bell Rock and lighthouses. You will need someone else to take you on that voyage or just head off yourself… You never know what you might find!

Jane Adamson

SELECT BIBLIOGRAPHY

LIFE AND DEATH

All That Remains: A Life in Death by Sue Black (2018)

Written in Bone: Hidden Stories in What We Leave Behind by Sue Black (2020)

CROSSING THE TAY

The High Girders: The True Story of The Tay Rail Bridge Disaster-The Victorian Dream that Ended in Tragedy by John Prebble (1956)

Poet McGonagall: The Biography of William McGonagall by Norman Watson (2010)

Poetic Gems by William McGonagall, Foreword by Billy Connnolly (1992)

Billy Connolly’s World Tour of Scotland. Six-part series. Broadcast by the BBC 1994. Running time: 180 minutes

JUTE, THEATRE AND EXPLORATION

The Remaking of Juteopolis: Dundee circa 1891-1991 Edited by Christopher A. Whatley (1992) Abertay Historical Society Publication No. 32

South: The Story of Shackleton’s 1914-1917 Expedition by Sir Ernest Shackleton (1919)

HEART OF THE CITY: A BIOLOGIST, MUSEUM CURATOR, BARD, MISSIONARY AND AUTHOR

Growing and Forming: Essays on D’Arcy Thompson Edited by Matthew Jarron, Cathy Caudwell and Meic Pierce Owen (2017) Abertay Historical Society Publication No. 58

Frida Kahlo’s Visit to the Taybridge Bar Song by Michael Marra

Dundee Women’s Trail: Twenty Four Footsteps over Four Centuries (2008) Text by Mary Henderson and Dundee Women’s Trail www.dundeewomenstrail.org.uk

Creatures of Fancy: Mary Shelley In Dundee by Gordon Bannerman, Kenneth Baxter, Daniel Cook and Matthew Jarron (2019) Abertay Historical Society Publication No. 60

THROUGH WEST FERRY, BROUGHTY FERRY AND ONTO THE NORTH SEA

George Chinnery (1774-1852) Artist of India and the China Coast by Patrick Conner (1993)

For the Desperate Dan sculpture and the murals of the side of the DC Thompsonand so muchDundee’s Public Art: maps, trials and information www.publicartdundee.org

George Chinnery, Mrs. Katherine Ann Neish, oil on canvas, 30.1 x 25.9cm. (image courtesy of Dundee Art Galleries and Museums)